A new Pinocchio film returns to the tale's dark origins

The story of the puppet who yearns to become a real boy has tickled the fancy of many directors, sometimes with unexpected results

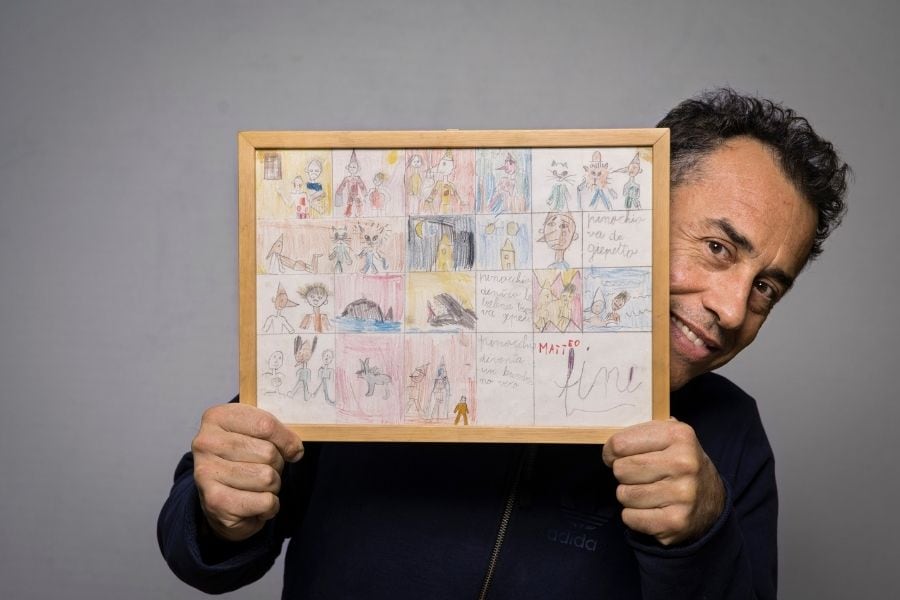

The Italian director Matteo Garrone, holding the Pinocchio storyboard he drew when he was a child, in Rome, Dec. 21, 2020. The director hopes to surprise audiences this Christmas with a very literal retelling of the children’s classic. (Gianni Cipriano/The New York Times)

The Italian director Matteo Garrone, holding the Pinocchio storyboard he drew when he was a child, in Rome, Dec. 21, 2020. The director hopes to surprise audiences this Christmas with a very literal retelling of the children’s classic. (Gianni Cipriano/The New York Times)

ROME — Carlo Collodi’s “Pinocchio” is one of the world’s best-loved children’s books, translated into over 280 languages and dialects, and the subject of countless films and television series.

When Italian director Matteo Garrone decided to put his spin on “Pinocchio,” which opens in cinemas in the U.S. on Christmas Day, he took an unusual path: fidelity to the original “The Adventures of Pinocchio,” first published as a book in 1883.

The result is a far more realistic, at times darker, telling of the tale. Gone are the cute kitties, goldfish and cuckoo clocks that enlivened Disney’s 1940 version. There are no catchy songs destined to become classics.

Instead, Garrone has immersed his “Pinocchio” in the landscape — and the poverty — of mid-19th-century Tuscany so accurately that when the film meanders into the fantastical — and it often does — it feels wondrous.

After all, Collodi, whose real name was Carlo Lorenzini, wrote the book to be a cautionary tale. Initially, it was serialized in a children’s magazine and Collodi abruptly ended the puppet’s adventures after chapter 15, leaving Pinocchio hanging — and very much dead — from a tree. After readers objected, Collodi’s editor persuaded him to prolong the story, with its many twists and turns, to the proverbial happy ending.

©2019 New York Times News Service