Chile rewrites its constitution, confronting climate change head-on

After months of protests over social and environmental grievances, 155 Chileans have been elected to write a new constitution amid what they have declared a "climate and ecological emergency."

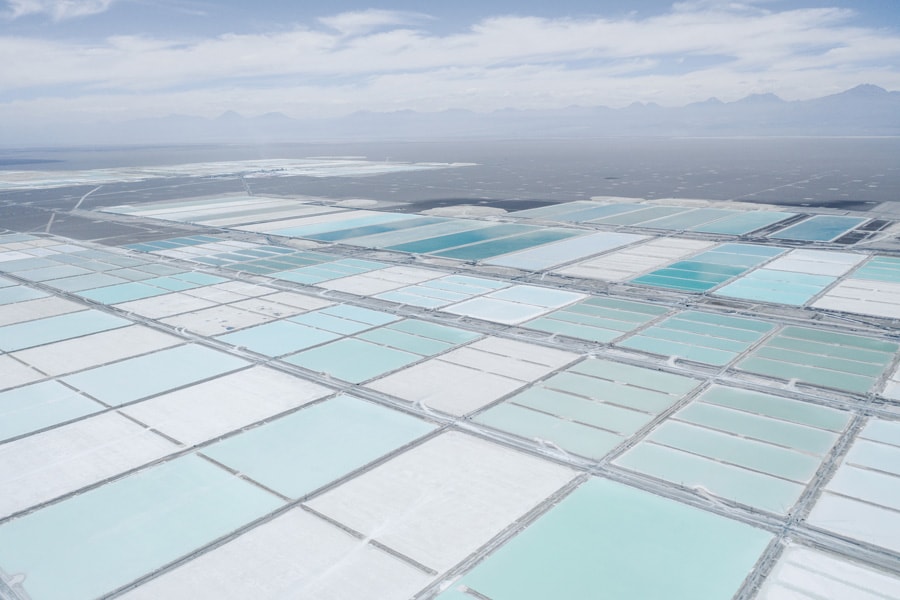

An aerial view of evaporation ponds at a lithium plant in the Atacama Desert of Chile, an essential component of batteries that is mined from the country’s salt flats, Dec. 15, 2021. After months of protests over social and environmental grievances, 155 Chileans have been elected to write a new constitution amid what they have declared a “climate and ecological emergency.” (Marcos ZegersThe New York Times)

An aerial view of evaporation ponds at a lithium plant in the Atacama Desert of Chile, an essential component of batteries that is mined from the country’s salt flats, Dec. 15, 2021. After months of protests over social and environmental grievances, 155 Chileans have been elected to write a new constitution amid what they have declared a “climate and ecological emergency.” (Marcos ZegersThe New York Times)

SALAR DE ATACAMA, Chile — Rarely does a country get a chance to lay out its ideals as a nation and write a new constitution for itself. Almost never does the climate and ecological crisis play a central role.

That is, until now, in Chile, where a national reinvention is underway. After months of protests over social and environmental grievances, 155 Chileans have been elected to write a new constitution amid what they have declared a “climate and ecological emergency.”

Their work will not only shape how this country of 19 million is governed. It will also determine the future of a soft, lustrous metal — lithium — lurking in the salt waters beneath this vast ethereal desert beside the Andes Mountains.

Lithium is an essential component of batteries. And as the global economy seeks alternatives to fossil fuels to slow down climate change, lithium demand — and prices — are soaring.

Mining companies in Chile, the world’s second-largest lithium producer after Australia, are keen to increase production, as are politicians who see mining as crucial to national prosperity. They face mounting opposition, though, from Chileans who argue that the country’s very economic model, based on extraction of natural resources, has exacted too high an environmental cost and failed to spread the benefits to all citizens, including its Indigenous people.

©2019 New York Times News Service