China conflict: Why the US needs Indonesia

The Biden administration has spent much of its first year in office shoring up support among allies and partners who share Washington's concerns about Beijing but were bruised by four years of Donald Trump

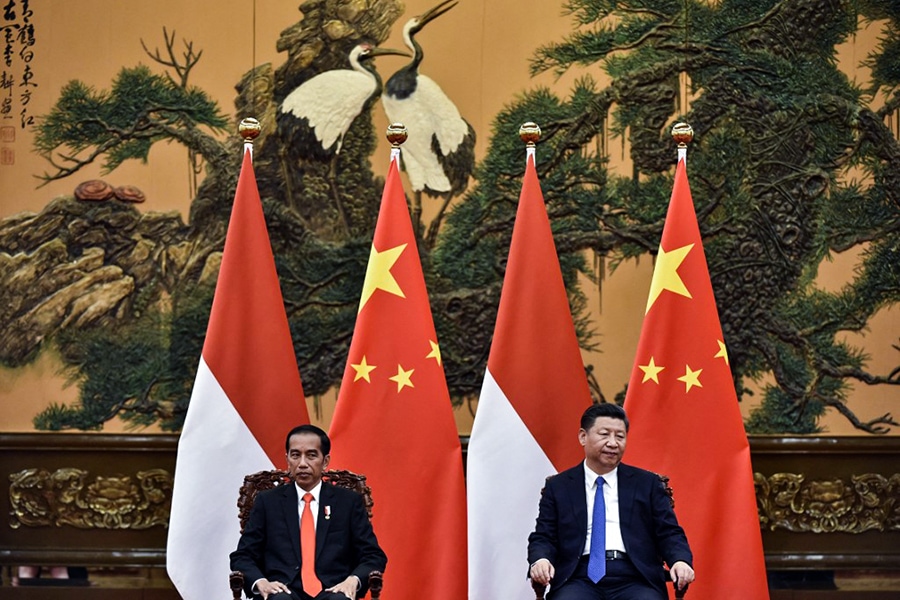

President Joko Widodo of Indonesia, left, and President Xi Jinping of China in 2017.

President Joko Widodo of Indonesia, left, and President Xi Jinping of China in 2017.

Image: Kenzaburo Fukuhara / Pool / AFP

When President Biden met his Indonesian counterpart, Joko Widodo, last month in Glasgow, he praised Indonesia’s “essential” leadership in the Indo-Pacific and “strong commitment” to democratic values.

But the reality of American engagement with the world’s third-most-populous democracy has been more tepid than these warm words imply, belying Indonesia’s position as the leading Southeast Asian power and a vital balancing force in the geopolitical contest of our time between the United States and China.

The Biden administration has spent much of its first year in office shoring up support among allies and partners who share Washington’s concerns about Beijing but were bruised by four years of Donald Trump. That period of reassurance was important and necessary. But if the real goal of strategic competition with China is to ensure a “free and open Indo-Pacific” — rather than pursuing great-power competition for its own sake — America cannot rely on a few fast friends who share its worldview.

Washington needs to move closer to nonaligned, and sometimes quarrelsome, emerging powers like Indonesia and help them become less reliant on China.

©2019 New York Times News Service