China scores a public relations win after WHO mission to Wuhan

The WHO team opened the door to a theory embraced by Chinese officials, saying it was possible the virus might have spread to humans through shipments of frozen food, an idea that has gained little traction with scientists outside China

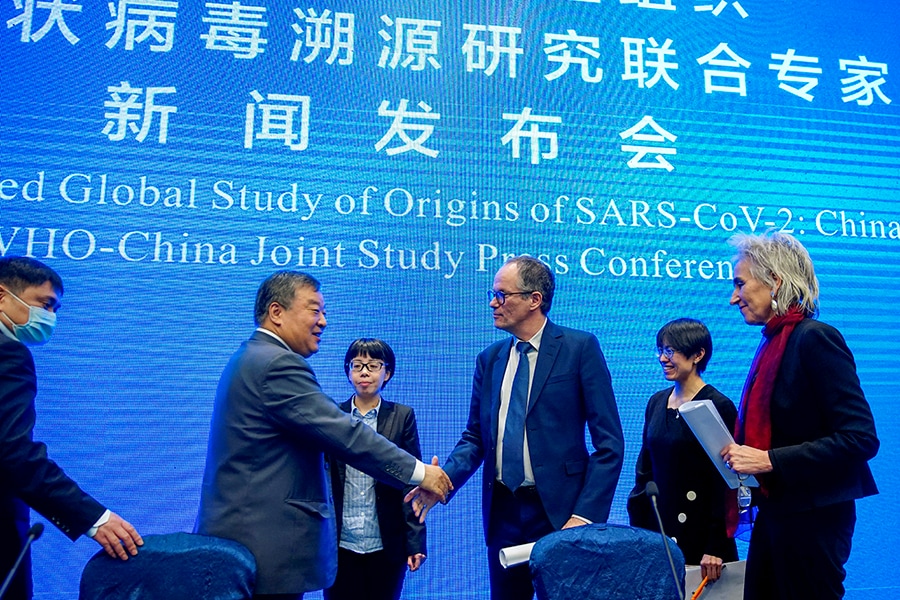

Peter Ben Embarek, a member of the World Health Organization (WHO) team tasked with investigating the origins of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), shakes hands with Liang Wannian, head of expert panel on COVID-19 response at China's National Health Commission, next to Marion Koopmans at the end of the WHO-China joint study news conference at a hotel in Wuhan, Hubei province, China February 9, 2021.

Peter Ben Embarek, a member of the World Health Organization (WHO) team tasked with investigating the origins of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), shakes hands with Liang Wannian, head of expert panel on COVID-19 response at China's National Health Commission, next to Marion Koopmans at the end of the WHO-China joint study news conference at a hotel in Wuhan, Hubei province, China February 9, 2021.

Image: Aly Song / REUTERS

For months, China resisted allowing World Health Organization experts into the country to trace the origins of the global pandemic, concerned that such an inquiry could draw attention to the government’s early missteps in handling the outbreak.

After a global uproar, the Chinese government finally relented, allowing a team of 14 scientists to visit laboratories, disease-control centers and live-animal markets over the past 12 days in the city of Wuhan.

But instead of scorn, the WHO experts on Tuesday delivered praise for Chinese officials and endorsed critical parts of their narrative, including some that have been contentious.

The WHO team opened the door to a theory embraced by Chinese officials, saying it was possible the virus might have spread to humans through shipments of frozen food, an idea that has gained little traction with scientists outside China. And the experts pledged to investigate reports that the virus might have been present outside China months before the outbreak in Wuhan in late 2019, a long-standing demand of Chinese officials.

“We should really go and search for evidence of earlier circulation wherever that is,” Marion Koopmans, a Dutch virus expert on the WHO team, said at a three-hour news conference in Wuhan, where the experts presented their preliminary findings alongside Chinese scientists.

©2019 New York Times News Service