Dilip Kumar, who brought realism to Bollywood, dies at 98

As one of the country's earliest method actors, he was often compared to Marlon Brando, another early adopter of the technique, even though Kumar credited himself with using it first

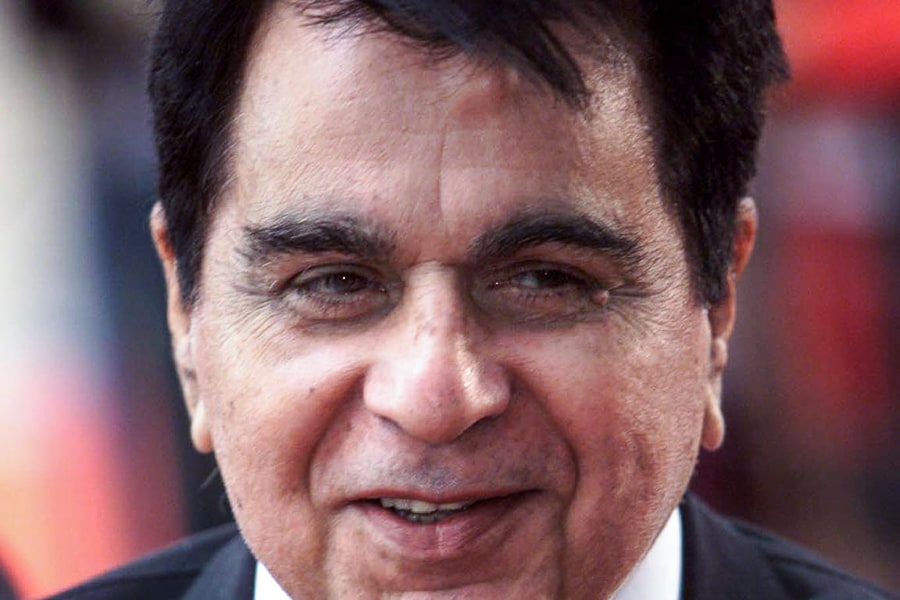

Image: Jonathan Evans / Reuters

Image: Jonathan Evans / Reuters

Dilip Kumar, the last of a triumvirate of actors who ruled Hindi cinema in the 1950s and ’60s, died Wednesday at Hinduja hospital in Mumbai, India. He was 98.

His death was confirmed by Faisal Farooqui, a family friend, who posted a brief statement on Kumar’s official Twitter account.

In post-independence India, Kumar and two other stars set about defining the Hindi film hero. Raj Kapoor reflected the newly minted Indian’s confusion: his signature role was that of the Chaplinesque naïf negotiating a world that was losing its innocence. Dev Anand, known as the Gregory Peck of India, embodied a Western insouciance that still lingered; he became a stylish matinee idol.

Kumar, though, delved deeply into his characters, breaking free from the semaphoric silent-movie style of acting popularized by megastars like Sohrab Modi and Prithviraj Kapoor.

As one of the country’s earliest Method actors, he was often compared to Marlon Brando, another early adopter of the technique, even though Kumar credited himself with using it first.

©2019 New York Times News Service