How Mitch McConnell Delivered Justice Amy Coney Barrett's Rapid confirmation

Ignoring cries of blatant hypocrisy, the Senate leader pushed through pre-election approval, capping off his reshaping of the judiciary

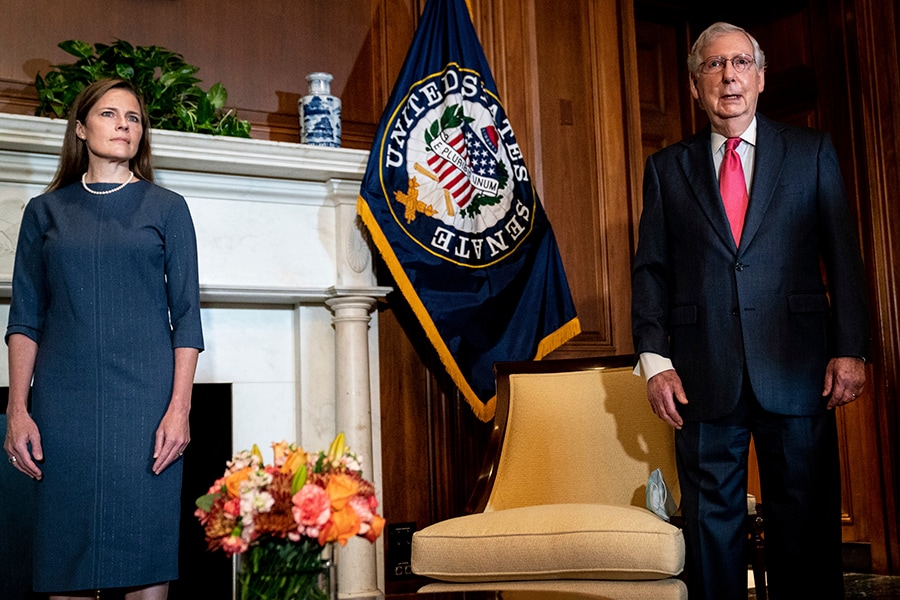

Judge Amy Coney Barrett, President Donald Trump's nominee for the Supreme Court, meets with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) on Capitol Hill in Washington, Sept. 29, 2020. The confirmation of Barrett caps an enduring achievement that McConnell could not even have imagined four years ago: the confirmation of three Supreme Court justices, the appointment of fifty-three appeals court judges, and scores of new young conservative judges presiding on the district courts — all delivered under his close supervision and direction.

Judge Amy Coney Barrett, President Donald Trump's nominee for the Supreme Court, meets with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) on Capitol Hill in Washington, Sept. 29, 2020. The confirmation of Barrett caps an enduring achievement that McConnell could not even have imagined four years ago: the confirmation of three Supreme Court justices, the appointment of fifty-three appeals court judges, and scores of new young conservative judges presiding on the district courts — all delivered under his close supervision and direction.

Image: Erin Schaff/The New York Times

WASHINGTON — Within hours of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death last month, Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., was on the phone with President Donald Trump, assuring him that Senate Republicans would not hesitate to fill the sudden vacancy despite the imminent election.

But he offered a word of warning to the president: “This will be the hardest fight of my life,” McConnell said, according to an aide. “We have to play this perfectly.”

There was good reason for caution. McConnell, the Senate majority leader, had moved just as quickly in 2016 to block President Barack Obama from filling a Supreme Court vacancy nine months before the election, saying voters should decide who selected the next justice. Now, he was proposing to brazenly reverse course and muscle through a nominee who would cement a conservative court majority in the middle of presidential voting and a pandemic that had reached the Senate.

That approach would set in motion the most partisan Supreme Court confirmation in modern history, a sprint that shredded past Senate practice and skirted some arcane rules. It drew outrage from Democrats who called the entire process illegitimate, and set up a tight timetable that could have been derailed by any number of unexpected events.

But on Monday night, as Sen. Chuck Schumer of New York, the Democratic leader, denounced the confirmation of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court as one of the “darkest days” in Senate history, McConnell sat nearby on the Senate floor, smiling and chuckling to himself with the knowledge that he was minutes from a vote that would fulfill his highest goal.

©2019 New York Times News Service