How Pfizer Plans to Distribute Its Vaccine (It's Complicated)

Success will hinge on an untested network of governments, companies and health workers

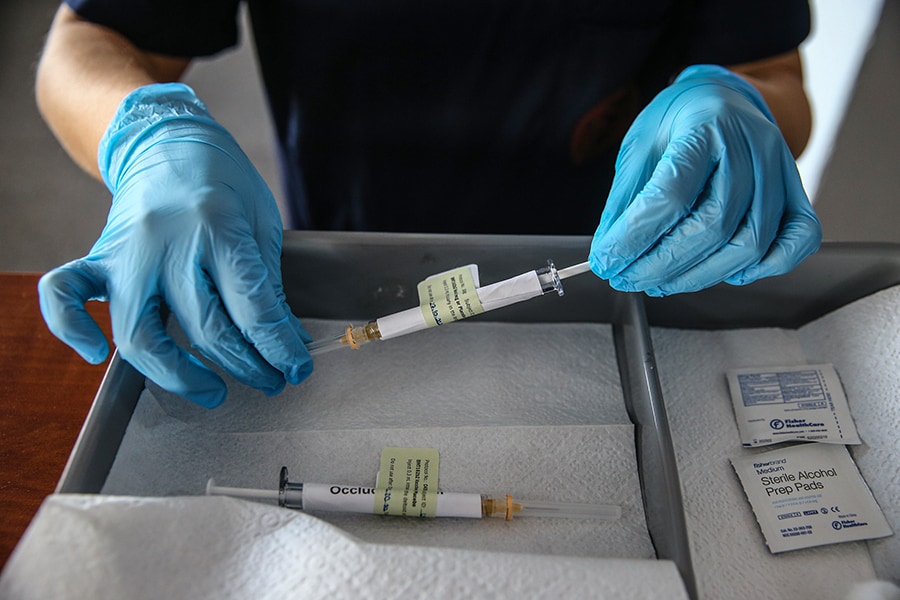

A health care worker holds an injection syringe of the phase 3 vaccine trial, developed against the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic by the U.S. Pfizer and German BioNTech company, at the Ankara University Ibni Sina Hospital in Ankara, Turkey on October 27, 2020. This vaccine candidate, within the scope of phase 3 studies, was injected to volunteers in Ankara University Ibni Sina Hospital

A health care worker holds an injection syringe of the phase 3 vaccine trial, developed against the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic by the U.S. Pfizer and German BioNTech company, at the Ankara University Ibni Sina Hospital in Ankara, Turkey on October 27, 2020. This vaccine candidate, within the scope of phase 3 studies, was injected to volunteers in Ankara University Ibni Sina Hospital

Image: Dogukan Keskinkilic/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

For months, scientists and public health experts have been saying the most crucial part of defusing the COVID-19 pandemic will be developing a safe and effective vaccine. So it was cause for celebration this week when Pfizer announced that an early analysis showed its vaccine candidate was more than 90% effective.

Now the drugmaker, the government and the public health community face a new challenge: quickly making millions of doses of the vaccine and getting them to the hospitals, clinics and pharmacies where they will be injected, two separate times, into people’s arms.

If Pfizer receives authorization for its vaccine from the Food and Drug Administration in the coming weeks, as expected, the company in theory could vaccinate millions of Americans by the end of the year, taking advantage of months of planning and decades of experience.

“I am very confident. I live and breathe this,” Tanya Alcorn, a Pfizer executive overseeing the supply chain for the vaccine, said in an interview Wednesday. “We have developed a system that does not waste any precious vaccine.”

But Pfizer — like other manufacturers that may soon be authorized to roll out their vaccines — does not fully control its own destiny. The effort will hinge on collaboration among a network of companies, federal and state agencies, and on-the-ground health workers in the midst of a pandemic that is spreading faster than ever through the United States.

©2019 New York Times News Service