How the US helped, and hampered, the escape of Afghan journalists

Major American news organisations ended up dealing directly with Qatar's government, which had cultivated a relationship with the Taliban

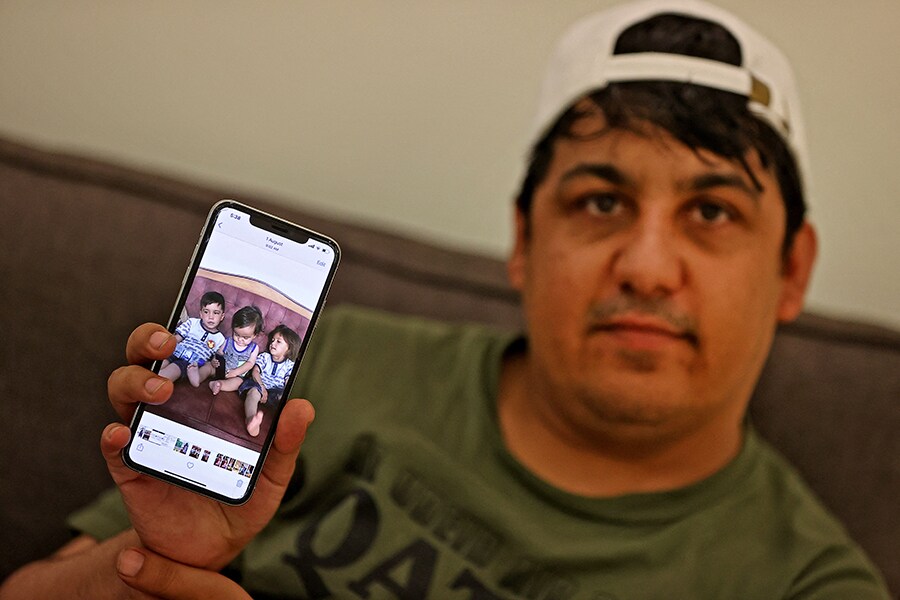

Afghan refugee Ahmad Wali Sarhadi, 28, displays a pictue of his children on his phone as he rests at his accommodation at Park View Villas, a Qatar's 2022 FIFA World Cup residence designated to host the event's guests and participants, transformed into a housing centre for Afghan refugees, in Doha, he was able to get out after he sent panicked emails to the international news media outlets he had worked for. His children remain in Afghanistan. (Photo by KARIM JAAFAR/AFP via Getty Images)

Afghan refugee Ahmad Wali Sarhadi, 28, displays a pictue of his children on his phone as he rests at his accommodation at Park View Villas, a Qatar's 2022 FIFA World Cup residence designated to host the event's guests and participants, transformed into a housing centre for Afghan refugees, in Doha, he was able to get out after he sent panicked emails to the international news media outlets he had worked for. His children remain in Afghanistan. (Photo by KARIM JAAFAR/AFP via Getty Images)

As American news organizations scrambled to evacuate their Afghan journalists and their families last month, I reported that those working for The New York Times had found refuge not in New York or Washington, but in Mexico City.

The gist of that column was that even outlets like the Times and The Wall Street Journal had learned that the U.S. government would not be able to help at critical moments. In its place was a hodgepodge of other nations, led by tiny Qatar, along with relief groups, veterans associations and private companies.

Some State Department officials took umbrage at the idea that the U.S. government had abandoned Afghans who had worked alongside American journalists during the 20-year war. In telephone interviews last week, Secretary of State Antony Blinken and two other officials closely involved in the evacuation of journalists and many others from Afghanistan made the case to me that the U.S. exit should be seen as a success. They pointed to the scale of the operation — 124,000 people evacuated, in total — as the ultimate American commitment to Afghanistan’s civil society.

“We evacuated at least 700 media affiliates, the majority of whom are Afghan nationals, under the most challenging conditions imaginable,” Blinken said in an interview Friday. “That was a massive effort and one that didn’t just start on evacuation day.”

©2019 New York Times News Service