In the wake of India's Covid-19 crisis, a 'black fungus' epidemic follows

The coronavirus pandemic has drawn stark lines between rich nations and poor, and the mucormycosis epidemic in India stands as the latest manifestation

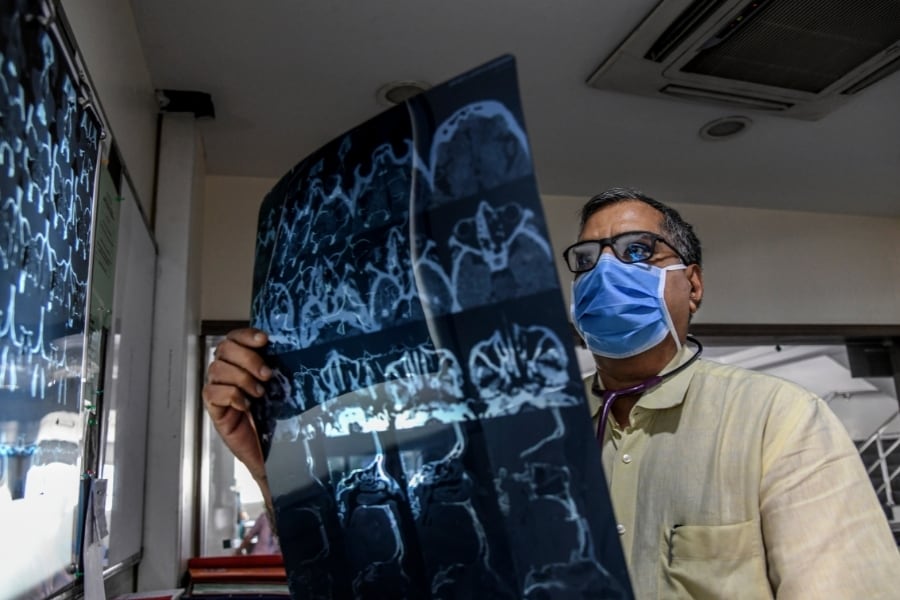

Dr. Atul Patel examines a scan of a patient recovering from mucormycosis at Sterling Hospital in Ahmedabad, June 10, 2021. The deadly disease has sickened former coronavirus patients across the country. Doctors believe that hospitals desperate to keep Covid-19 patients alive made choices that left them vulnerable. (Atul Loke/The New York Times)

Dr. Atul Patel examines a scan of a patient recovering from mucormycosis at Sterling Hospital in Ahmedabad, June 10, 2021. The deadly disease has sickened former coronavirus patients across the country. Doctors believe that hospitals desperate to keep Covid-19 patients alive made choices that left them vulnerable. (Atul Loke/The New York Times)

AHMEDABAD, India — In the stifling, tightly packed medical ward at Civil Hospital, the ear, nose and throat specialist moved briskly from one bed to the next, shining a flashlight into one patient’s mouth, examining another’s X-rays.

The specialist, Dr. Bela Prajapati, oversees treatment for nearly 400 patients with mucormycosis, a rare and often deadly fungal disease that has exploded across India on the coattails of the coronavirus pandemic. Unprepared for this spring’s devastating Covid-19 second wave, many of India’s hospitals took desperate steps to save lives — steps that

may have opened the door to yet another deadly disease.

“The pandemic has precipitated an epidemic,” Prajapati said.

In three weeks, the number of cases of the disease — known by the misnomer “black fungus,” because it is found on dead tissue — shot up to more than 30,000 from negligible levels. States have recorded more than 2,100 deaths, according to news reports. The federal health ministry in New Delhi, which is tracking nationwide cases to allot scarce and expensive antifungal medicine, has not released a fatalities figure.

©2019 New York Times News Service