What if the unvaccinated can't be persuaded?

The unvaccinated often hold their views strongly, and many are making considered, cost-benefit calculations given how they weigh the risks of the virus, and the information sources they trust to inform them of those risks

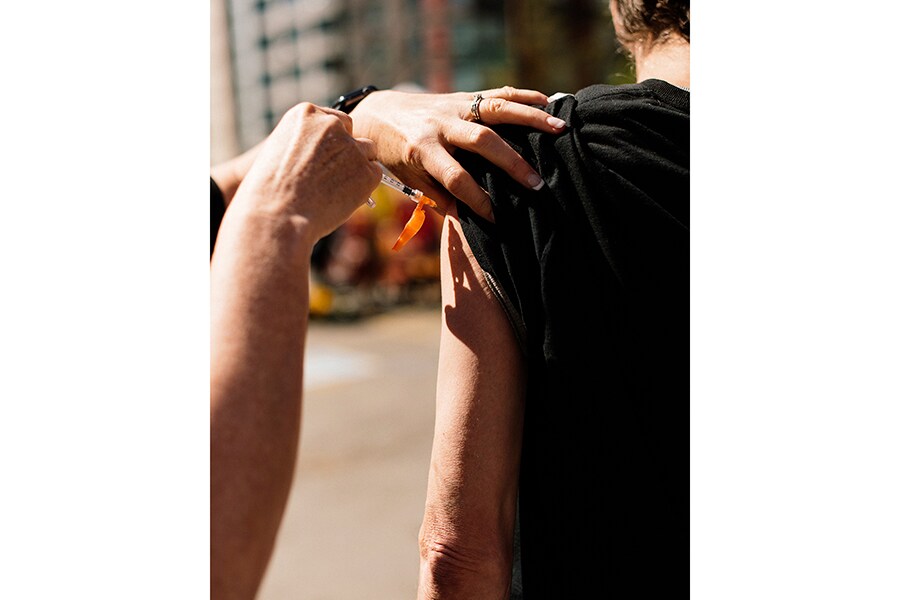

A COVID-19 vaccine is administered in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, April 22, 2021. “If policymakers want to change their minds, they have to change their calculations by raising the costs of remaining unvaccinated, the benefits of getting vaccinated or both,” writes New York Times columnist Ezra Klein. Image: Alana Paterson/The New York Times

A COVID-19 vaccine is administered in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, April 22, 2021. “If policymakers want to change their minds, they have to change their calculations by raising the costs of remaining unvaccinated, the benefits of getting vaccinated or both,” writes New York Times columnist Ezra Klein. Image: Alana Paterson/The New York Times

I hate that I believe the sentence I’m about to write. It undermines much of what I spend my life trying to do. But there is nothing more overrated in politics — and perhaps in life — than the power of persuasion.

It is nearly impossible to convince people of what they don’t want to believe. Decades of work in psychology attest to this truth, as does most everything in our politics and most of our everyday experience. Think of your own conversations with your family or your colleagues. How often have you really persuaded someone to abandon a strongly held belief or preference? Persuasion is by no means impossible or unimportant, but on electric topics, it is a marginal phenomenon.

Which brings me to the difficult choice we face on coronavirus vaccinations. The conventional wisdom is that there is some argument, yet unmade and perhaps undiscovered, that will change the minds of the roughly 30% of American adults who haven’t gotten at least one dose. There probably isn’t. The unvaccinated often hold their views strongly, and many are making considered, cost-benefit calculations given how they weigh the risks of the virus, and the information sources they trust to inform them of those risks. For all the exhortations to respect their concerns, there is a deep condescension in believing that we’re smart enough to discover or invent some appeal they haven’t yet heard.

If policymakers want to change their minds, they have to change their calculations by raising the costs of remaining unvaccinated, the benefits of getting vaccinated, or both. If they can’t do that, or won’t, the vaccination effort will most likely remain stuck — at least until a variant wreaks sufficient carnage to change the calculus.

You can see the weakness of persuasion in the eerie stability of vaccination preferences. The Kaiser Family Foundation has been surveying Americans about their vaccination intentions since December. At that time, 15% said they would “definitely” refuse to get vaccinated, 9% said they would get a shot only “if required,” and 39% wanted to “wait and see.”

©2019 New York Times News Service