- Home

- UpFront

- Global News

- Will Japan confront China? A visit to Washington might offer a cue

Will Japan confront China? A visit to Washington might offer a cue

Ever since the United States forged an alliance with Japan during its postwar occupation, Tokyo has sought reassurance of protection by Washington, while Washington has nudged Tokyo to do more to secure its own defence

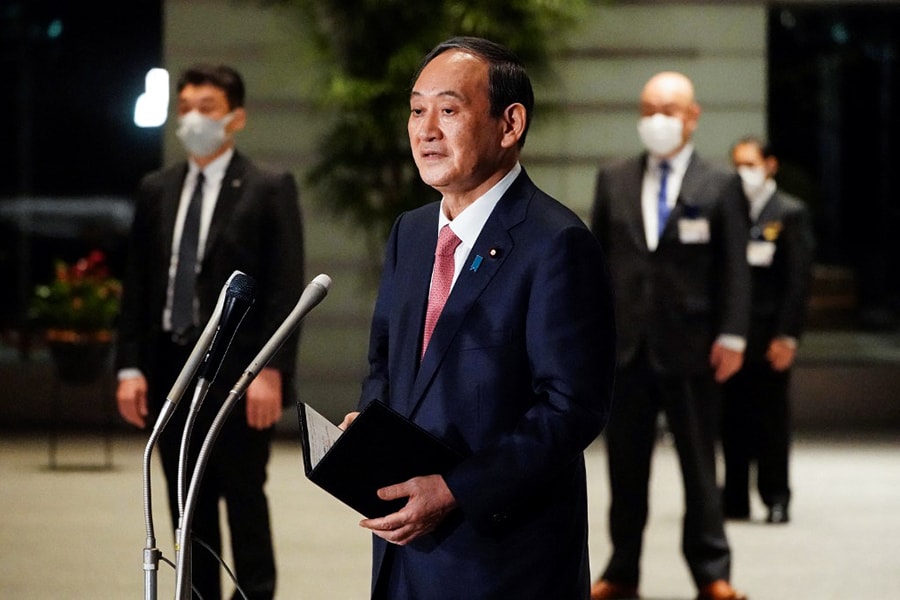

Image: Eugene Hoshiko / POOL / AFP

Image: Eugene Hoshiko / POOL / AFP

TOKYO — As he visits Washington this week, it would seem as if Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga of Japan could take a victory lap.

Suga is the first foreign leader to be invited to the White House by President Joe Biden, who has vowed to reinvigorate alliances. Japan already had the distinction last month of being the first international destination for the new U.S. secretaries of state and defense. And Suga will not have to contend with threats of higher tariffs or the need for constant flattery that drove Biden’s mercurial predecessor.

But even as relations between the two countries are calming, Japan faces a perilous moment, with the United States prodding it to more squarely address the most glaring threat to stability in Asia: China.

It is the latest step in an age-old dance between the two countries. Ever since the United States forged an alliance with Japan during its postwar occupation, Tokyo has sought reassurance of protection by Washington, while Washington has nudged Tokyo to do more to secure its own defense.

For decades during the Cold War, the pre-eminent threats seemed to come from Europe. Now, as Suga goes to Washington, Japan confronts encroaching dangers in its own backyard.

“We’re in a completely new era where the threat is focused on Asia, and Japan is on the front line of that threat,” said Jennifer Lind, an associate professor of government at Dartmouth College and a specialist in East Asian international security.

“The U.S.-Japan alliance is at a crossroads,” Lind said. “The alliance has to decide how do we want to respond to the growing threat from China and to the Chinese agenda for international order.”

Analysts and former officials said it was time for Japan to expand its thinking about what a summit with its most important ally could accomplish.

Typically, a Japanese prime minister has a slate of agenda items to tick off. This visit is no different. The two leaders are expected to talk about the coronavirus pandemic, trade, the importance of securing supply chains for components like semiconductors, the North Korean nuclear threat and shared goals on climate change.

“Usually when a Japanese prime minister goes to the U.S., there is a sort of shopping list: ‘Would you say this, would you reassure us about that,’” said Ichiro Fujisaki, a former Japanese ambassador to the United States.

This time, he said, “that’s not what we should do. I think we should talk big about the world and Asia-Pacific.”

Such bold statements would run counter to Japanese officials’ deep-seated instincts. They have tended to avoid mentioning China or its most sensitive interests, preferring vague and sweeping language about the need to maintain a free and open Indo-Pacific region.

But as China has repeatedly ignored diplomatic or legal efforts to contain its aggressive actions in both the South China and East China seas, some say Japan needs to be more specific about what it might do in the event of a military conflict.

“Who doesn’t want freedom and openness?” said Jeffrey Hornung, an analyst at the RAND Corp. “By signing up for those things, you subtly take a jab at China. But what are you going to do when those things you say you’re going to defend come under attack?”

Japanese leaders usually use summits with American presidents to seek assurances that the United States, which has about 50,000 troops stationed in Japan, would defend the country’s right to control the uninhabited Senkaku Islands. Over the past year, China, which also claims the islands, has sent boats into or near Japan’s territorial waters around the islands with increasing frequency.

Perhaps the biggest risk of conflict, though, is in the Taiwan Strait, where China has been dispatching warplanes to menace the democratic island, which Beijing considers a rogue territory. When Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Tokyo last month, they and their Japanese counterparts issued a statement stressing “the importance of peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait.”

If Biden and Suga include similar language in a joint statement this week, it would be the first time that the leaders of the United States and Japan have mentioned Taiwan explicitly since 1969. At that time, President Richard Nixon and Prime Minister Eisaku Sato issued a statement in which the Japanese leader said that “the maintenance of peace and security in the Taiwan area was also important for peace and security of Japan.”

The gritty details of how Japan might support the United States and Taiwan in the case of an invasion by Beijing are probably beyond the scope of this week’s talks. While Biden is unlikely to make any blunt demands that Japan pay more for its defense, as President Donald Trump did, Biden could amplify recent signals from his administration about efforts to deter China. One possibility is that Japan could be asked to host long-range missiles, a proposal that would probably face significant domestic opposition.

Biden and Suga are expected to discuss not just China’s military actions but also its human rights record, as well as the coup in Myanmar — likely areas of difference between the leaders.

The Biden administration has called China’s repression of Uyghur Muslims in the Xinjiang region a genocide and imposed sanctions on Chinese officials. It has also placed sanctions on military generals in Myanmar. But Japan tends to be more circumspect in addressing human rights or taking direct actions such as economic sanctions.

Tobias Harris, an expert on Japanese politics at Teneo Intelligence in Washington, said the Suga administration addressed human rights only “rhetorically.”

“When you actually look at what they are doing,” he said, “they are trying to somewhat keep their options open.”

For Japan, which conducts vast trade with China and has investments in Myanmar, there is a clear fear of backlash and an understanding that Beijing can turn off the spigot at any time.

Tsuneo Watanabe, a senior fellow at the Sasakawa Peace Foundation in Tokyo, noted that at the outset of the pandemic, China designated certain medicines and surgical masks as “strategic goods” and stopped shipping them to Japan. “We can no longer rely on the free flow of goods from China,” Watanabe said.

Some Japanese officials say Suga should not rush to follow Biden’s harder line on China and Myanmar. Kunihiko Miyake, a former Japanese diplomat who advises Suga, said Japan’s approach to such countries is “more dialogue than punishment.”

A person familiar with the thinking of Suga and his Cabinet who spoke on the condition of anonymity said that despite the rising tensions, Japan did not want to upset its relationship with China. The person said that Japan had to send a clear message to China on issues like the rule of law but that the two sides should also maintain high-level communication.

Biden may also try to pull Japan along on climate change. Both Washington and Tokyo are working toward drastic reductions in carbon emissions, and Biden is hosting a climate summit next week. One goal is to persuade Japan to stop its financial support of coal projects abroad, which it has already started to reduce.

Suga may hope that a fruitful trip to Washington will bolster his standing at home, where he is politically vulnerable. The Japanese public is unhappy with his administration’s management of the pandemic and a slow vaccine rollout (although Suga has been cleared to travel after being vaccinated himself), and a majority oppose the decision to host the Olympic Games this summer.

The trip’s success may depend in part on whether Suga develops a rapport with Biden. Seasoned watchers of Japan will be closely tracking Suga, who is not known for his charisma, especially after his predecessor, Shinzo Abe, spent considerable time and effort wooing Biden’s predecessor.

“We have two older and very traditional politicians in a lot of ways,” said Kristin Vekasi, an associate professor of political science at the University of Maine. “I will be curious to see what they do.”

©2019 New York Times News Service