Bad at your job? Maybe it's the job's fault

A poorly designed job can work against even the most dedicated employee, setting the person up to fail. Robert Simons explains how to gauge whether an employee's position offers the right mix of organizational support and responsibility

Image: Shutterstock

When a worker struggles to meet the demands of a particular position, the problem may not be with the employee—maybe it’s the job’s design that is wrong.

A poorly designed job can work against even the most dedicated employee, setting the person up to fail. This creates a recipe for frustration and a path to burnout that is all too common in today’s workplace, says Robert Simons, the Charles M. Williams Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School.

“Today’s jobs are expanding in terms of what is expected of people, but the resources people get to do those jobs is not expanding,” says Simons. “People feel more pressure to own their roles and they’re stressed because they’re being pulled in a lot of different directions, but they’re not getting the help they need.”

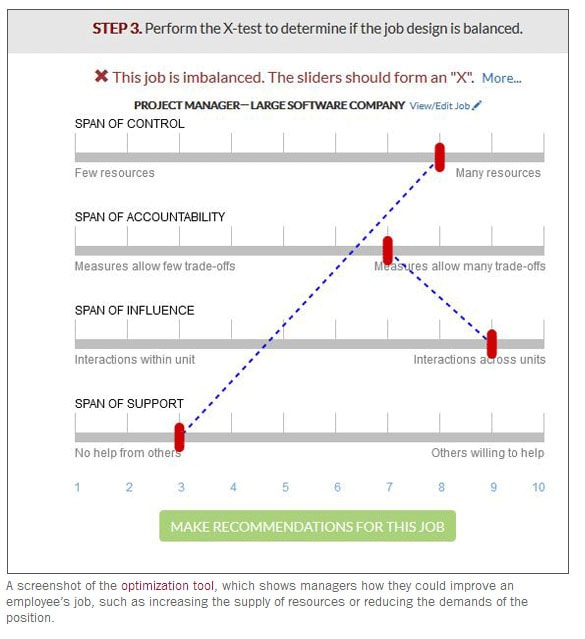

The idea that an employee’s poor performance might be a case of a badly designed job is not intuitive for managers. So Simons created a solution: a free online job design optimization tool that allows companies to plug in information about a particular job to test whether the person in that role is getting the right mix of responsibility and support from the organization.

After all, for any job to succeed, the supply of resources available to the worker must be in balance with the responsibilities of the job, says Simons. It’s a simple supply-and-demand lesson that should ring true for anyone who has taken an economics course, “but we’ve never thought of it in terms of a job design before.”

“In many companies today, people are being held accountable for measures that are much wider than the resources and the amount of control they are given,” Simons says. “They control this narrow slice, but their jobs are tied to things like revenue growth and profitability. The missing piece is the support they are given to accomplish their goals.”

When using the tool, a job can be evaluated by answering four questions:

1. What resources does the person in that job control to accomplish a task? This list of resources may include people, budgets, and balance sheets.

“Just imagine you are looking to take a job somewhere and they want you to drive $100 million in revenue,” Simons explains. “You’ll want to ask: ‘How many people are you giving me to do that? What does my budget look like?’ If you’re being asked to do these important things, the first thing you’ll want to know is what resources you’re getting.”

2. What measures are used to evaluate that individual’s performance? This looks at: How will the person be held accountable, how will the person’s performance be tracked, and what factors will be evaluated to determine success?

Evaluation measures could include sales or revenue goals, the number of patents filed or products launched, or customer satisfaction levels.

3. Who does the individual need to influence to achieve goals? This refers to the amount of time and attention a person in a particular job must devote to interacting with others and nudging people where they should go, including collecting data, probing for new information, or attempting to influence the work of others.

The amount of influence will be narrow if the job is self-contained, meaning a person sits at a desk all day without interactions with others, whereas the span of influence will be wide if the person must touch many people, especially others outside the unit, to succeed.

A manager at an innovative, customer-focused company like Amazon needs a wide span of influence to figure out how to make the customer happy. One individual doesn’t control all the resources at that company, so that person relies on talking to others about delivery speed and other features to make sure the customer is being served.

4. How much support can the individual expect when reaching out to others for help? A job is bound to fail if the people who control resources refuse to help.

“In some organizations, it’s every man or woman for themselves,” Simons says. “You eat what you kill, and no one is willing to help others. If a person is asked to do a lot of things—innovate, spend time influencing others—but the person can’t get help when he reaches out for it, that job is doomed.”

At many organizations, leaders should try to foster an atmosphere where people have a deep commitment toward helping one another. This can be costly and difficult to pull off because it means creating a culture where people feel a shared sense of purpose, identify with the group, have trust in coworkers, and share in rewards.

Leaders should be honest when answering these questions if they want to figure out how to fix a job. Their answers will vary from job to job and organization to organization, depending largely on the goals of a particular position in relation to the company’s overall strategy.

The tool allows for making adjustments to improve the position, such as increasing the supply of resources or reducing the demands of the job. Often when a job doesn’t work, it’s a matter of simplifying it—and also being clear about what that worker should not do.

“You often have an individual who has to spend too much time in meetings or too much time on managing this matrix, and the person is spread too thin. You add more and more stuff, and no one thinks of the cost in terms of energy, lack of focus, and diversion of priorities,” Simons says. “If the job is too complicated, can we make it so that the person doesn’t have to get agreement from four people before moving forward? Can we keep that person from being put on one more committee?”

It can get sticky because reallocating tasks and resources means other workers will be affected. To help with managing this balance, the tool can be used to compare two jobs at the same time.

In some cases, leaders discover that resources are being wasted because one person has been given too many. Those resources can be reallocated and used more wisely, or the person in that role could be asked to step up more.

Simons did a case study of different roles at Google. It turned out that the sales and marketing folks were overtaxed, while the demands were too soft on software engineers. “The tool gave us insight for each job on how to improve it,” he says.

Why that job is so hard

Prior to developing the online tool, Simons used a paper model to analyze jobs with his MBA and executive education students in his management and strategy execution courses. It dawns on a good third of the business executives in his courses that either their own roles or other positions they have created in their organizations don’t have enough support to meet the demands of the job.

“It’s fun to do this with executives because you see the lightbulbs going off in their heads. I’ve had a number of people tell me, ‘Now I understand why that job is so hard,’” Simons says. “It shines a light on the problem.”

And at a time when workers are expected to have a laser focus on customers, executives also know good employees will opt to work for organizations that invest in the resources the staff needs to accomplish that task.

“The more you want to be customer-focused in a highly competitive environment,” Simons says, “the more you have to give people in the organization the tools they need to succeed.”

Dina Gerdeman is a senior writer for Harvard Business School Working Knowledge

This article was provided with permission from Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.