Customers at the back of the line are anxious-can you keep them from leaving?

The irrational anxiety associated with being last in line can lead to unhappy customers, according to new research by Ryan Buell. But there are ways to make people happier while they wait—and keep them from abandoning the queue

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

Nobody likes being last. We avoid picking the cheapest wine on the menu or the final donut in the box. “And we hate being picked last in gym class,” says Harvard Business School professor Ryan Buell.

“Humans are very social creatures, and we are driven to compare ourselves to others,” says Buell, the UPS Foundation Associate Professor of Service Management in the Technology and Operations Management Unit. “When we are feeling bad, one way we cope is by comparing ourselves to people who are worse off than we are.”

Perhaps nowhere is this more apparent than while we are waiting in line. “Every line has an end and there is an identifiable person who occupies it,” says Buell. “They know they’re last and everyone around them knows it as well.”

The anxiety we feel about being last can affect how consumers experience waiting for a product or service—and can affect companies’ bottom lines —Buell explains in a new working paper, “Last Place Aversion in Queues (pdf).”

Buell’s research investigates how operations can be designed to better engage their customers, and how operational choices affect customer behaviors and firm performance.

We all spend a surprising amount of time waiting our turn; by one estimate, Americans wait in line 37 billion hours a year—118 hours for every person. Rationally, you might think that the only thing that matters during those times is what’s going on in front of you—how fast the cashier is ringing up customers, say, or how many tellers there are at the bank counter.

Buell’s research shows, however, that people are also concerned with what’s happening behind them, especially when there’s no one there.

“What seems to be driving this,” says Buell, “is our inability to make a downward social comparison. If I can’t look behind me and see someone else is willing to wait longer than me, I start to question whether waiting in line is worthwhile.”

Lining up for an experiment

He conducted a series of experiments to learn how being last affects consumer behavior. To get started, Buell and Harvard student Jay Chakraborty observed customers at a local grocery store with five checkout lanes—a total of 286 customers over a cumulative five hour span.

“These were relatively short lines, but what was surprising was how much jockeying for position there was,” he says. Customers regularly switched lines to try and decrease their wait time. Significantly, though, once someone got in line behind them, they tended to stay put. In fact, of the 71 customers who switched positions, 67 of them did it while they were in last place.

Short of stopping customers and asking them why they switched, it’s difficult to know exactly why they did so, or whether they were better off for their jockeying. To answer those questions, Buell set up an online experiment using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform.

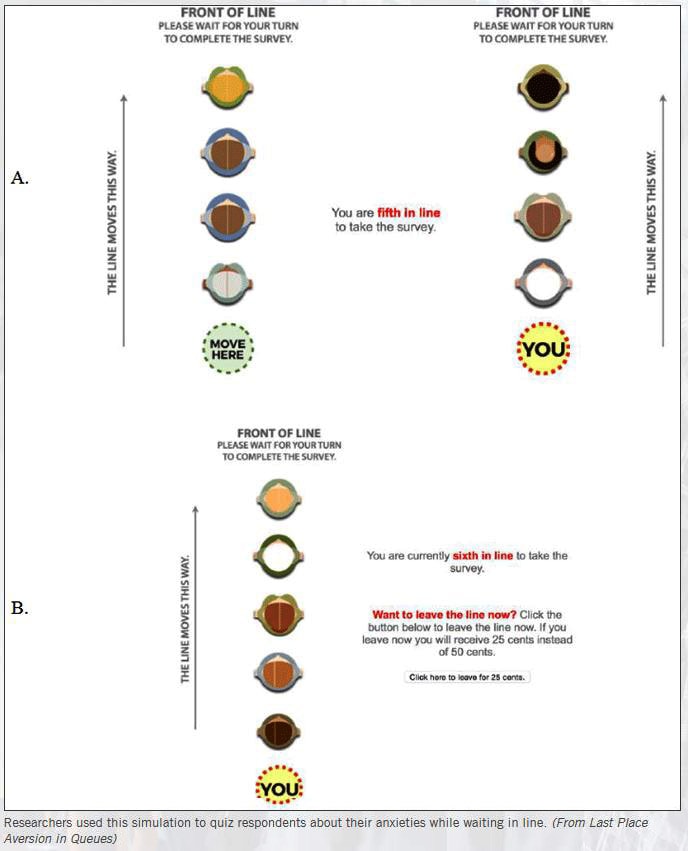

Respondents were told they would be paid 50 cents to answer a survey that took several minutes to complete. Before they could do so, they had to wait in a line of up to six people. Buell created a graphic representation of the queue so all participants could see where they were at all times. When they got to the front, he asked them how satisfied they were with their wait.

Controlling for their actual wait time and the number of people ahead of them, those who spent their entire wait in last place were 19 percent less satisfied with the experience than other participants. That translated to the equivalent of waiting an extra 70 seconds, the average time for two people. “People would have rather waited behind two extra people if they could just not have been in last place,” Buell concludes.

In variations on the experiment, he allowed people more control over their experience. The first variation included two lines, and allowed participants to switch between them at will. “Some people very comically switched back and forth multiple times,” Buell says. As with the grocery store observations, people switched most often when they were last in line—in fact, controlling for other factors, they were twice as likely to switch in that case.

While they often switched when the other line was shorter, they also switched when it was the same length or even longer—possibly because they hoped the other line would move more quickly. Tabulating the total time each participant spent in line, however, Buell found that those who switched at least once actually ended up spending an average of 57 seconds longer in line—meaning their aversion to being in last place cost them in the end. (Adding insult to injury, switchers also spent twice as long in last place.)

Buell caveats that in real waiting environments, there are visual cues that can help customers make strategic choices about when to switch, but that the experience of being in last on its own, seems to be enough to drive the behavior.

For the final experiment, Buell allowed people to quit waiting altogether in exchange for a reduced payment ranging from 5 to 45 cents. When the payment was close to the amount they would have received by sticking it out, people understandably chose to leave more often, but they were no more likely to leave when they were last in line. When the payments were far apart—meaning it was more valuable to wait in line—people were four times more likely to leave when they were last in line.

Real world application

Applying that to the real world, Buell sees a problem from an operational standpoint when customers are waiting for a service they find valuable and then decide to quit.

“That’s bad for them,” he says. “They don’t get to benefit from the service. But if you are the service provider, that’s not good for you either. You’ve got a customer walking out the door.”

To guard against that outcome, Buell recommends that service providers think carefully about how they set up their physical environments—for example, allowing the customers to focus on the service process rather than the line they’re waiting in. “Showing customers the work that’s being done to serve them can cause them to mind waiting less and value the service more,” he says.

In virtual environments such as call centers, they can do the opposite, emphasizing the line and the customer’s relative position in it when there is someone behind them. For example, they could not only say, “You are the fifth caller,” but “You are the fifth caller out of seven,” to give them a downward comparison. “Not knowing that we’re in last, and knowing that we’re not in last, both can make us more likely to stick around,” Buell explains.

Buell’s data also shows that the dissatisfaction with being in last place diminishes over time, so engaging with customers more quickly could help keep them patient. “When a barista comes up to you in line and asks, ‘Can I get something started for you?’ then you feel less pain from waiting,” Buell says, “plus you feel invested now and are less likely to give up.”

Lastly, business owners can use social comparison to their advantage by posting average wait times for different times of day, shifting the comparison consumers make from their companions in line to other customers waiting at other times.

“It would reveal to you that leaving now would not be a good strategy for you,” Buell says. At the same time, you could still take solace in the fact that someone else is less fortunate.

“Now you are thinking you’re so much better off than those poor suckers tomorrow.”

This article was provided with permission from Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.