Hard work isn't enough: How to find your edge

Life isn't fair, especially in the workplace. In Edge: Turning Adversity into Advantage, Laura Huang offers a new strategy for uncovering and showcasing your unique value in the face of obstacles.

Image: Shutterstock

Image: ShutterstockWe’re told that the secret to success is hard work. But the truth is, hard work alone doesn’t always pay off.

After all, career advancement isn’t always neatly tied to your skills, effort, or even the quality of your work. Some people gain easier access than others to the critical ingredients of money, time, and connections that part the workplace waters—even when they don’t have the best ideas or the most talent.

“It’s a myth that hard work is enough. We’ve all had experiences where we worked hard and still ended up losing out on a new job or a key promotion,” says Harvard Business School Associate Professor Laura Huang, who studies early entrepreneurship, where failure is common. “You can take two people who work equally hard, and one person will naturally have an advantage and achieve success, while the other can’t climb the corporate ladder.”

What often gets in the way: stereotypes about gender and race or perceptions about age and class. Indeed, vast research shows that certain groups, such as women and African Americans, have a tougher time getting ahead.

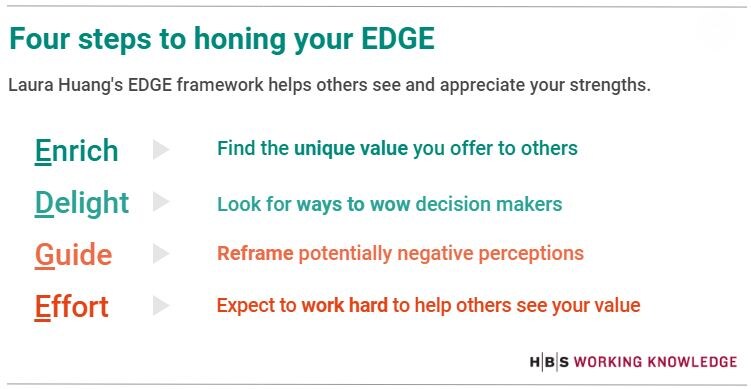

Yet Huang argues that we can’t let other people’s stereotypes or their views of our faults or limitations, right or wrong, hold us back. Instead, we have to focus on finding our “edge”—the unique qualities that set us apart—and take strategic steps to make other people see our value and open the doors that will take us where we want to go.

Life isn’t fair. We can’t just wait around for people to make the right decisions for us,” says Huang, who witnesses plenty of wheel-spinning among the hundreds of entrepreneurs she has researched, including some who can’t get funding for ingenious business ideas. “So how do we take all the disadvantages stacked against us and flip them in our favor to succeed within an imperfect system?”

It all starts with confronting potential barriers or shortcomings and molding them into assets, Huang says in her new book Edge: Turning Adversity into Advantage.

The five tips below, based on advice in the book, are intended to help further your career, whether you’re hunting for a first job or find yourself at a key inflection point: frustrated with your current standing in the workforce and grappling with how exactly to position yourself for success.

1. Identify the “basic goods” you have to offer that will enrich others

It’s what cofounders Arch “Beaver” Aplin III and Don Wasek did when they opened their first Buc-ee’s gas station in Lake Worth, Texas, in 1982. They focused on the things they figured travelers needed most: gas, cheap ice, and clean restrooms.

Today Buc-ee’s is a road trip destination, with more than 30 sprawling stores offering Texas-themed gifts, Buc-ee’s brand beef jerky, plenty of gas (as many as 120 pumps at one store), mountains of ice to refill coolers, and giant spotless restrooms (with up to 33 urinals in a single men’s room).

In evaluating your own career goals, Huang recommends taking a page from Buc-ee’s and asking yourself:

What are the strengths that set you apart from the pack and provide value?

When people are interacting with you, what is the most basic thing they expect you to deliver?

To zero in on your basic goods, trust your gut in figuring out what skills you bring to the table—and what you don’t. If your brilliant business idea relies on software programming and you’re not a programmer, switch gears.

“Pinpoint your basic goods and define your circle of competence, then operate inside that perimeter,” Huang advises.

2. Own your constraints and encourage others to see past them

In Huang’s freshman year of college, she was shocked to fail a writing assignment. When she asked the professor where she went wrong, he said, “Don’t worry. Since English is not your native language, it will take you some time to get the hang of writing.”

Suspecting the instructor had judged her work unfairly based on her last name, she decided to own the constraint and write her next essay on the challenges of growing up as a nonnative English speaker. Evidently the professor detected none of her sarcasm and gave her a B-minus.

Huang avoided the mistake many people make: counting themselves out of the running based on the constraints other people place on them—or ones they place on themselves. In fact, research shows that men are more likely to apply for jobs even when they don’t fit most of the criteria in a job ad, whereas women are quicker to dismiss themselves and shy away from applying at all.

“We can all become too focused on the things we think we can’t do or the things people say we can’t do,” Huang says. “We have to embrace our constraints, rather than dodge them, but we also can’t let them define us.”

When applying for a job, it’s good to be aware of the stumbling blocks that might thwart an offer, but it’s even more important to emphasize the talents that do match the job criteria, so you can shine to the point of making any shortcomings seem meaningless.

“Every diamond has certain flaws, but someone else might not see those flaws unless you let them show,” Huang says. “If you focus on the angles that make you sparkle brightly, that’s what people will see.”

3. Focus on ways to delight others

The best way to pacify skepticism others may feel about you is to surprise and delight them, Huang says.

In a meeting with a buyer for Neiman Marcus, clothing designer Sara Blakely was talking up the benefits of her product, Spanx, but sensed she was losing the buyer’s attention. So Blakely asked the woman to follow her to the bathroom and showed her what she looked like without wearing Spanx, followed by the slimming effect after slipping the undergarments on. The buyer was delighted not only with the product, but with the brilliance of the pitch, and the deal was sealed.

“Find those points of connection to surprise people in a memorable, engaging way that gives them a pleasant feeling,” Huang says. “You can’t be boring because people won’t hear you.”

The most delightful interactions are improvisational, so it’s OK to develop high-level plans for making a good impression prior to an important meeting, but strike a balance between preparing and staying spontaneous in the moment.

“If you over-prepare, it can immobilize you and prevent you from bobbing and weaving,” Huang says. “You don’t want to be tethered to a script that feels forced. You want to stay alert and light on your feet.”

Yet delighting others isn’t necessarily about being charming, entertaining, or charismatic. It’s about entering high-stakes situations with ideas for wowing others with the unexpected.

Years ago, Huang’s colleague at an engineering firm did just that when she found herself among a group of laid-off employees who were told they could decide whether to continue working or take personal time during a two-month severance period. While most workers took the two months off to find a new job or take a break, the woman kept showing up to the office, and when new assignments were floated, she offered to take them on.

At the end of the two months, the woman was involved in so many critical business operations, she received multiple offers from senior leaders to stay—and she went on to work for the company for 40 years.

4. Guide how others perceive your work and worth

The levers that enable success are often outside our control, and the people pulling them tend to make decisions based on their view of our competence and character. Huang says you need to be aware of how others see you and guide their perceptions, redirecting them when necessary to influence whether they appreciate your value.

Huang recalls setting up slides before teaching a new MBA course at HBS when a student entering the room mistook her for an IT support specialist. “Easy mistake, right?” Huang says. “Asian woman equals tech support, not professor.”

When people make snap judgments about us, we can empower ourselves to shift forces in our favor. Knowing she might not fit the typical image of a professor—because she’s “too young and too female,” as she puts it—Huang opened her class by saying, “I know it may look like I’m here to sell you Girl Scout cookies,” then redirected her students’ judgments about her age, race, and femininity by outlining her professional credentials.

“Some people think this is gross and too strategic,” Huang says. “But when people form perceptions about us, they need to be guided in how they think about us, rather than relying on assumptions about who we are.”

That’s what Cyrus Habib, who lost his eyesight at age 8 to retinoblastoma, has done. When he ran for lieutenant governor of Washington in 2016, well-meaning friends expressed concern about whether the blind man could handle door-to-door canvassing.

Habib responded by telling them he had gone “from Braille to Yale,” had found his way through the Port Authority Bus Terminal, plus had navigated the thousand-year-old dorms and cobblestone streets at Oxford. By confronting what others saw as a deficit head on, Habib turned his obstacle into a way to connect with voters, and ultimately, he won the election. “I guide [people] away from who they think I should be, to who I am,” he says in Huang’s book.

5. Be the proverbial “prom queen”

When Huang was in the last year of her doctoral program and was nervously seeking her first academic appointment at a college, her advisor encouraged her to “be the prom queen.” Because, she said, “everyone wants to date the prom queen.”

Huang felt far from the academic equivalent of the prom queen. Her alma mater, University of California, Irvine, was not considered a “high-caliber school” among the top 50 research institutions. And unlike many of her peers, she lacked a single published research paper, the main currency for academics vying for plum positions.

Her advisor argued that none of that should matter. Rather than trying to contort our own experiences into what we think is the standard trajectory toward success, being the prom queen means capturing your special aura by explaining where you have come from and where you are going to guide other people to understand your value. And that value doesn’t have to be the same as everyone else’s.

In meetings with job search committees, Huang showed college officials her potential by focusing on what made her stand out: her research into the previously unanswered question of how gut feelings figure into entrepreneurial investment decisions. Much to her surprise, the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania hired her as an assistant professor.

“Being the prom queen means you shouldn’t care if you haven’t taken the typical path like everyone else,” Huang says. “You should focus on the qualities you do have that make people sit up and pay attention.”

People who put in the most effort often feel jaded when their work doesn’t speak for itself, Huang says. It’s important to set bitterness aside and find the right way to influence the outside perceptions that drive so many decisions about our careers.

When it comes to achieving success in any field, hard work is a given, Huang says. Gaining an edge requires what she calls “hard work, plus”—and that “plus” amounts to enriching, delighting, and guiding other people so they can see your value.

“Hard work will work harder for you if you tie it together with other strategies to give it headwinds and tailwinds,” she says. “That’s when you’re unstoppable.”

Dina Gerdeman is senior writer at Harvard Business School Working Knowledge. HBS Digital Media Producer Amelia Kunhardt produced the video interview.

This article was provided with permission from Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.