Disruptors sell what customers want and let competitors sell what they don't

By "decoupling" activities that consumers value from the ones they don't, enterprising digital startups are wreaking havoc on established firms. Thales Teixeira discusses his research on the second wave of Internet disruption

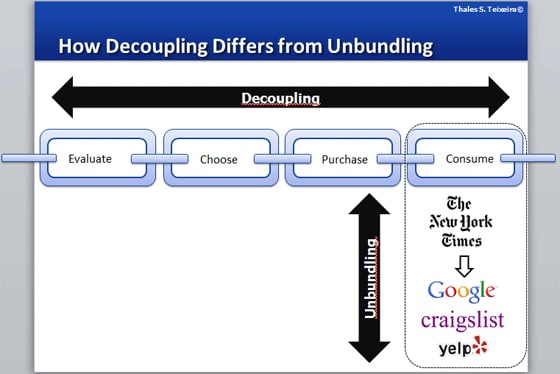

Over the past two decades, entire industries have been disrupted by Internet competitors who "unbundled" their content and delivered it to consumers in new ways. Newspapers lost out to Google and Craigslist, record companies to iTunes and Spotify, and travel agencies to Expedia and Hotels.com.

Despite this upheaval, it seemed some businesses were immune to the digital onslaught—companies whose products and services couldn't be easily turned into 1's and 0's and put online. "A television set can't be digitized. A telephone can't be digitized. So those companies seemed to be safe," says Thales Teixeira, an assistant professor at Harvard Business School in the Marketing unit.

But not anymore.

THE SECOND INTERNET WAVE

A second wave of Internet disruption threatens not only electronics and telecom businesses, but also industries as diverse as taxi services, banking, and cosmetics. Unlike the unbundling that allows customers to pick and choose the content they consume (be it articles, music tracks, or airline tickets), Teixeira identifies the fueling factor in this case as "decoupling"—separating out activities that customers want from those that they don't.

Watching TV and watching commercials, for example, have traditionally gone together—the former creating value for the consumer, the latter capturing it for the company. When TiVo came along, it allowed viewers to record the shows they wanted without all of those annoying ads. Another early disruptor, Skype, takes advantage of existing wifi networks to allow users to make calls on their mobile phones without purchasing extra minutes.

"Decoupling separates two or more activities that were previously forced to be co-consumed by an established firm," explains Teixeira, who details the phenomenon in a recent paper, The Decoupling Effect of Digital Disruptors, coauthored with HBS Research Associate Peter Jamieson (HBS MBA'14).

The companies spearheading the trend look for opportunities to deliver what is of most value to the consumer while stripping away what's not—leaving the rest to be delivered by the established player.

In the case of Skype, for example, the service decouples talk/text from the underlying (and expensive) connectivity provided by the telecom company. More recently, says Teixeira, it has fueled changing consumer habits as well, such as a growing preference for sharing items rather than owning them, and encouraging "showrooming" where shoppers visit stores only to test products—then buy them more cheaply online.

The user benefits from lower cost, lower effort, or saved time. Want to wear the latest fashions but can't afford the hefty prices for designer originals? Rent the Runway allows fashionistas to use those dresses and accessories at affordable rates. The company has decoupled the value part of the process—experiencing haute couture—from the non-value-creating portion of the transaction, buying expensive merchandise with a limited wear life.

PriceGrabber is a decoupler, too. Traditional consumer electronic retail stores depend on customers to come to their showrooms and tire-kick TVs and sound systems before buying. But the PriceGrabber app and those from plenty of other competitors allow consumers to find cheaper products online—even as they stand in the store. The service decouples the value-creating portion of the process—testing and trying—with the non-value portion—buying.

The automobile industry has been challenged as well, by ride-sharing firms such as Zipcar, Uber, and Relay Rides that allow drivers to use a car on demand owned by the firm, by the driver, or by strangers, respectively, without the cost of purchasing or maintaining one. Exploiting decoupling opportunities has allowed these upstarts to build a business on the back of larger companies without having to develop their own infrastructure first.

"We used to say that auto companies, telecoms, and big retailers weren't at risk of disruption within their industries, because there were such high barriers to entry; you could never compete with their scale," says Teixeira. "Decoupling allows you to say, we are not going to compete by building a car manufacturing supply chain, a telephony network or a big retail footprint. We are going to use that available infrastructure to our advantage. These startups are like fleas on the backs of dinosaurs too big to do much about it."

DECOUPLING DOWN THE CONSUMPTION CHAIN

One key distinction between unbundling and decoupling is that while the former takes place only at the point of consumption, the latter can take place anywhere along the chain of testing, choosing, and purchasing products or services.

In some cases, companies are virtually banding together to replace nearly all aspects of a transaction. Take buying cosmetics. It used to be customers went to a cosmetics store such as Sephora to sample products, purchase them, and then return to replenish after supplies depleted.

Now they can sample cosmetics through Birchbox, which conveniently sends monthly samples to their home; purchase them for the first time through Amazon, where prices are often cheaper; and finally when they know which products they like, they can replenish them direct from cosmetics manufacturers such as Kiehl's, which offers subscriptions to loyal customers. By having each company specialize in one activity, the companies together do everything more efficiently for the customer.

Of course, managing all of these different suppliers of services can be a hassle for consumers. Customers implicitly weigh three factors in making a decision to decouple: money ("How much more cheaply can I buy it?"); effort ("How much more difficult will it be to get it?"); and time ("How long will I have to wait for it?")

Different people may place different value on those factors, he says, some potentially opting for the more expensive but more convenient one-stop shopping of traditional retailers—rather than say, spending the extra time showrooming for a television or booking a Zipcar.

On the whole, however, there is a clear trend towards more and more decoupling as innovative companies make it cheaper, easier, and quicker for consumers to do so using digital technologies and business models.

THE INCUMBENTS' CHALLENGE

As competitors attempt to wedge their way between incumbents and their customers, decoupling presents a difficult challenge.

One counter-strategy is what Teixeira calls recoupling. "Intuitively, the first order of defense is to say, let's just not allow our customers to do it," he says. That might mean lobbying for legislation, suing in court, or making customers sign contracts that prevent decoupling. After Aereo allowed viewers to stream TV programs over the Internet by picking up broadcast signals, TV networks sued for copyright infringement and forced the startup out of business. Similarly, taxi companies are now actively lobbying local governments to curtail Uber.

Other companies use alternative means of recoupling. Digital video recorder companies like TiVo have grown popular with TV watchers in part because of the ability to fast forward through ads—enabling the decoupling of TV shows from commercials. To counter that threat, some TV programmers have increased product placement and even inserted pop-up ads in the programs themselves forcing those who watch the show to watch the ad.

Some of the hottest battles are being fought over showrooming—the practice whereby consumers visit a store to check out items in person before buying cheaper online (decoupling browsing from buying). Celiac Supplies, a specialty food store in Brisbane, Australia, charges customers $5 for "just looking," refunding the fee if an item is purchased. "The problem with this approach is that it's trying to build a dam around your consumers and force them to do something they are not naturally inclined to do," says Teixeira. "Sooner or later they will find a way out, or a company will find a way out for them."

A better strategy to follow is "rebalancing," which realigns a company's activities in such a way that value is claimed by the firm every time the firm creates it. Best Buy has taken a bite out of showrooming not by forcing customers to buy in-store, but rather by rebalancing its own revenue sources. Realizing that its manufacturers have the most to lose if customers can't try out their wares in store, Best Buy has begun charging shelving costs to electronics makers in order to feature their products. "If you buy or don't buy, Best Buy is still making some money," says Teixeira. And with that increased revenue, the company is now able to offer a "price-match guarantee" that allows customers to instantly buy at the same price for which a product is advertised online.

In another rebalancing tactic, some American telecoms have recently ceded the field to Skype by providing unlimited calling for a flat fee with many phone plans. "Essentially, they are saying that this activity no longer has value to consumers, so we can't capture value ourselves," says Teixeira. At the same time, these companies have increased charges for basic connectivity to the Internet, which customers need to access services such as Skype.

DECOUPLING THE FUTURE

Now the decouplers are turning to the future.

One industry Teixeira sees as ripe for the process is banking, whose model relies on offering checking and savings accounts to get customers in the door and ready to be marketed to with more profitable products such as home mortgages. Already, entrepreneurial competitors are pecking around the margins of banking—Paypal offers essentially the equivalent of an online checking account, and other companies are getting in on the action.

Another industry he sees as vulnerable is television and cable, with joint risk of decoupling and unbundling. While they may have won the battle against Aereo, their business model, which forces customers to buy programming by the bundle rather than a la carte, leaves cable companies vulnerable to competition online from folks like Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon Prime, which have all left commercials behind in favor of a subscription model.

"The whole issue of cutting the cord is a huge risk for them," says Teixeira. It's likely a sign of things to come that sports network ESPN, available only on pay-cable services, this month announced its participation on Dish Network's Web-based Sling Box service.

Not every company is susceptible to decoupling, however. In some cases where it is too costly, labor intensive, or inconvenient for customers to wait for services, customers may prefer to deal with traditional firms.

"Some products like electronics you don't mind waiting a few days for Amazon to deliver—others like fresh groceries you need it now, in the store ," says Teixeira. "It's unlikely people will ever decouple showrooming from buying milk online."

If the recent explosion of digital disruptors is any indication, however, few companies or industries are immune from decoupling by enterprising entrepreneurs able to find ways to extract value from others' established infrastructure. Established companies would do well to brace themselves for the attack of these fleas—or else risk going the way of the dinosaurs.

Michael Blanding is a senior writer for Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.

This article was provided with permission from Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.