India's New Law of Energy

The politics around energy and climate change is playing out at multiple levels. Old alignments are breaking down and new ones are being forged

Addressing the Majlis Al-Shura, Saudi Arabia’s 150-member consultative assembly, is a rare honour granted to few outside the Kingdom’s ruling elite. Late in February this year, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was accorded this privilege shortly after he signed the Riyadh declaration, taking the relationship between the two countries beyond India’s thirst for crude oil to security, extradition and defence — issues that lie outside the boundaries of pure commerce.

Just months after Prime Minister Singh’s visit to Riyadh, it was oil diplomacy at its slickest in July, as foreign minister S.M. Krishna reopened talks with Iran to import gas from the giant South Pars field. Iran, with the largest reserves of gas, is critical for India’s future imports whether as CNG or through an Iran-Pakistan-India pipeline. Balancing interests between Iran and Saudi Arabia, two of the world’s most energy-rich nations but at opposite ends of the West Asian political spectrum, is an example of realpolitik that India has begun to excel in — driven entirely by the need to secure resources for growth.

India needs to sustain an economic growth rate of at least 8 percent over the next 25 years. Primary energy supply, says planning commission chief Montek Singh Ahluwalia, will have to grow by 3 to 4 times and electricity generation capacity by 5 to 6 times from the levels at the beginning of this decade — a lot of this will be fuelled by imported coal, oil, gas and uranium.

Today, most of India’s major geopolitical relationships involve an energy dimension. In an energy-constrained world, India’s energy strategy needs external policy support to succeed. India has to develop close co-operation with not only oil-rich countries but also oil importing and technologically advanced countries. It should also maintain a diplomatic balance on conflict issues to safeguard its energy interests. Proximity and historical linkages with some of the world’s hydrocarbon-rich regions such as West Asia, East Russia, Africa and Central Asia uniquely positions India to forge stronger energy ties with them.

Hedging Against Risks

India and China share similar concerns over energy security as skyrocketing demand forces them to look beyond their territorial boundaries. In a paper titled ‘Energy as a factor in India’s external politics’, written for research organisation Icrier, V. Raghuraman, Suman Kumar and Inder Raj Gulati point out that India has often lost the race to China in Kazakhstan, Ecuador and Myanmar. ONGC’s joint venture with Mittal Energy, OMEL, lost its bid to acquire a stake in PetroKazakhstan as China put its full diplomatic might behind securing the deal. Similarly, an agreement between ONGC Videsh Limited (OVL) and Shell to buy half of an offshore oilfield in Angola fell through after China lured Angola to exercise its right of refusal with a $2 billion aid package, they say. The deal by the Myanmar government to export gas to China through a pipeline or as LNG has stymied India’s plans to import gas from Myanmar. India, however, recently showed its changing diplomatic colours when it rolled out the red carpet for General Than Shwe of the Myanmarese military Junta that rules the country.

India should continue to hunt for resources for a different reason too — to hedge against price-volatility. The International Energy Agency says India’s dependency on imported energy will go up to 90 percent by 2030 as the economy grows. “Equity in a coalmine or an oilfield gives the advantage of a price hedge. We do not necessarily have to physically ship the minerals to India — they can be traded in local markets at the price of the day. The advantage is that if prices go up, we have locked in our price,” says Ashok Sinha, chairman of oil refining and marketing company Bharat Petroleum. His company has already made the moves, successfully staking out in diverse geographies such as the Brazilian offshore and Mozambique.

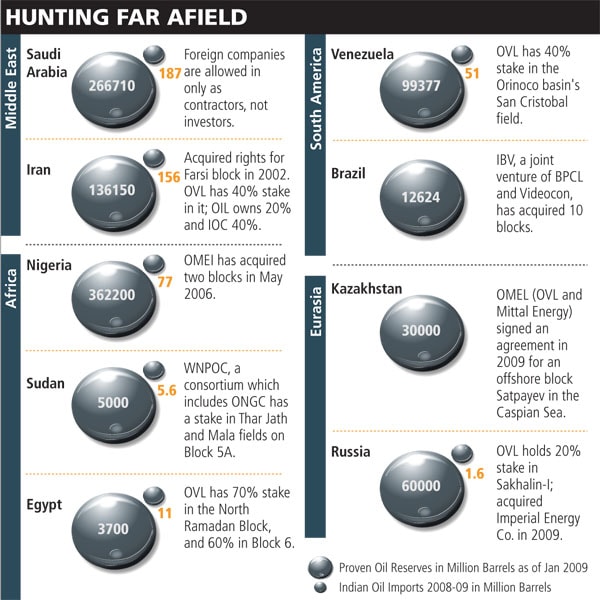

Over the past few years, Indian private and state-owned companies have hedged political risk by diversifying the search for oil to various parts of the globe. A few, led by government oil company OVL, moved into strife-torn parts of the African continent, Russia and Latin America, which many Western majors are reluctant to enter. The International co-operation division of the ministry of petroleum and natural gas is where a lot of the geopolitical mapping on energy takes place these days. It is not entirely a coincidence that the Indian ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Talmiz Ahmad, was earlier the additional secretary in charge of this wing.

The government has allowed OVL to push the diplomatic envelope and invest in Sudan, knowing fully well that this might close doors for the company in the United States. Private oil companies have been quick to follow the lead and are making their own way. Reliance Industries Ltd. (RIL) has begun exploration drilling in its two onshore blocks in Iraq’s semi-autonomous Kurdistan, signing up as an early mover even when the government in Baghdad strongly disapproved. RIL has also led the way in sourcing crude oil all the way from South America for its Jamnagar refineries, scripting options to the traditional West Asian suppliers.

RIL and Essar Oil have also bought into companies in the oil storage, retail and refining business in eastern Africa and Kenya, and are slowly expanding their footprint in the continent. ONGC’s buyout of Imperial Oil has given it an exposure to Russia which has proven oil reserves of 60 billion barrels, bulk of it in western Siberia.

Global Competition & Threats

Though India’s race with China gets the most public attention, India faces intense competition in the hunt for energy resources, particularly oil and gas, from the US, France, the UK, China and Malaysia. In Africa, for instance, the French oil company Total dominates the sub-Saharan oil industry, except in Sudan and Chad. In Nigeria, it is Shell and in Angola, Chevron-Texaco is the premier oil producer. American oil companies, particularly Exxon-Mobil and Chevron-Texaco, have aggressive plans for investments in Africa. Exxon-Mobil alone is planning to spend $15 billion in Angola in the next four years and around $25 billion across Africa during the next decade.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

Asian companies, China National Petroleum Corporation and Petronas from Malaysia are increasing their presence in Sudan, Angola and Chad even as they move in on Africa’s other potentially energy rich countries. The Chinese are rapidly increasing their presence in Central Asia and Latin America too by acquiring assets and long-term oil supply contracts.

India’s dependence on West Asian oil and gas resources will make for eternally increasing stakes in the security and stability of the region. Some scenarios India may be confronted with include al-Qaeda terrorist attacks on major oil facilities; the spread of instability from Iraq to other oil producing countries; Iranian interference with the passage of oil through the strategic Strait of Hormuz (possibly in confrontation with the US); and domestic instability or uncertain political transitions ranging from crises of leadership succession to radical changes in regimes.

Close political and economic relations with the countries of the region and greater co-operation with like-minded countries engaged there should, therefore, be important external policy objectives for strengthening oil security. Effective short-term and long-term strategies will need to be put in place, including a more active role in addressing West Asian problems and co-ordination against terrorist activities.

The security of sea routes and choke points is an important strategic necessity. This may require increased participation in naval activity in the Indian Ocean and docking/monitoring facilities in littoral states. Though India is geographically close to its main oil sources and sea routes from West Asia and Africa pass through fewer choke points compared to many other countries, the Straits of Hormuz and the Bab-el-Mandeb are significant concerns.

Politics of Climate Change

Over the last one year, a new blend of geopolitical equations has emerged, as various nations struggle to protect their own interests, after the Copenhagen summit failed to spell out how global warming will be contained. The BASIC group, comprising India, Africa, China and Brazil — all developing countries struggling with the clashing aims of rapid growth and capping emissions, has hitched its wagons to take on the rest of the world. The attempt is to speak in one voice and challenge the developed world’s attempts to enforce caps without any equity. The next showdown will be at the UN climate change conference at Cancun at the end of this year.

International lobbying on climate change is strongly in the economic domain, as large countries lobby for support among smaller nations. “Sharply divided interests on climate change have led to a breakdown of the traditional multilateral groupings,” says Kushal Pal Singh Yadav, co-coordinator of the climate change centre at the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE). Many countries are arm-twisting smaller nations to stand with them. One way to do this is through lending agencies like the World Bank that refuse to lend to countries that do not fall in line. “The United States for instance, keeps adding coal-based thermal power, while disapproving of developing nations that do the same,” he says.

Technologically advanced countries also stand to gain from selling new technologies to poor nations. Though India and China compete on the hunt for resources, they are aligned on climate change with the view that developed countries have to vacate some of the carbon-space, and allow the emerging economies to occupy it.

The latest flashpoint came up at Bonn in June, when fossil fuel producers like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait voted against ratcheting up action on carbon emissions. They argued that the action would “hurt their revenues”. On the other end of the spectrum is the AOSIS, the Alliance of Small Island states, which is clear that delays in implementing schemes to cut carbon emissions will make their nations uninhabitable. Delays by the US and Australia in ratifying such schemes has led to a gloomy sentiment about any possible results from Cancun later this year. Not surprising that India’s minister for environment and forests, Jairam Ramesh, is more realistic. He says that we cannot expect any miracles, a big change from his gung-ho position in Copenhagen a year ago.

Energy analyst and The Energy and Resources Institute (Teri) executive director Dr. Leena Srivastava, who has worked on several Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, says India’s view of global energy scenario will have to move away from the fossil fuel prism. “The move from resource-based collaboration with the leaders in the world to technology based tie-ups, is essential for new breakthroughs on clean technology. It will be suicidal if we do not start the transition to renewables right away,” she says.

Some rich countries do realise that the way forward is working with nations like India, which have the intellectual capital to invest in new research. British Prime Minister David Cameron said during his recent visit to India that the UK was looking at signing an agreement with India to develop new energy technologies to help address the problem of climate change. Cameron also said that one of the purposes of his visit to India was to increase collaboration in energy research.

The same idea, along with other strategic objectives, had pushed the George Bush administration to end India’s nuclear apartheid despite it not being a signatory to the nuclear non-proliferation treaty. Though some countries like Australia and Canada continue to hold out from helping India until it signs the NPT, others such as France, Russia and Kazakhstan have stepped forward. As its economic power grows, this stable democracy will attract the powers that be to its doorstep. As the prime minister of India’s former colonial master said: “I have come to your country in a spirit of humility. I know that Britain cannot rely on sentiment and shared history for a place in India’s future.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)