Why There Won't Be A Sustained Drop in Home Prices: Keki Mistry

HDFC's Keki Mistry explains why you will never see a sustained decline in home prices

With a hefty $35.25 billion by way of loan assets as at December 2013, Housing Development Finance Corporation (HDFC) is the market leader in home loans in India. HDFC’s average loan size is Rs 21.9 lakh and the institution has cumulatively financed 4.6 million housing units, with mortgage loans clocking a five-year compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 21 percent.

In an exclusive interview with Forbes India, HDFC’s vice chairman and CEO Keki Mistry busts some popular myths about housing in India. Excerpts:

Q. What are the trends you’re witnessing in the residential market in India?

The residential market in India, in my view, can never really come down in a significant manner. There might be dips here and there, there might be dips in some quarters where prices can come down, but if you take a five-year view, over the next five years prices have to go up. And the reason for this is, it’s a simple question of demand and supply. The demand for housing in India is structurally going to remain strong for a number of years.

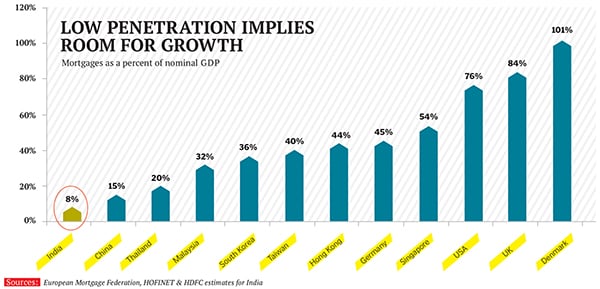

This will be so for a variety of reasons. One is penetration levels are very low in India. The second is urbanisation. More and more people will move to urban areas. Places that are today considered non-urban or rural will, over the next five, ten or fifteen years, get urbanised. That means more jobs will get created, more people will shift to these places and there will be demand for housing there. But my personal view why demand will remain strong will be the demographics in India. As we know, 60 percent of our population is below 30 years of age. And unlike the West, in India people do not go and buy a house in their 20s.

So the average age of a customer when he takes a loan from us or when he buys his first house would be 35 years plus. Somewhere in the 35-38 years band. And with 60 percent of our population below 30, there will come a stage in the next five, ten, fifteen years where all these people will get to a stage where they need housing. So the demand will be strong. Now, if demand is strong, then the only way prices can correct or come down is by increasing supply.

But supply has its own constraints. Infrastructure is the biggest one. In Mumbai, for instance, you could connect the northern part of the city with the southern part, and keep appropriate transport or pathways into various points of the city, and you could permit buildings to go higher. You create the schools, the colleges, the health centres, the hospitals, all the infrastructure a big city needs and you permit buildings to go higher, you’ll be increasing supply and prices will come down.

The other thing is, land is a major problem. In cities, getting land is a very challenging process. Purchase of land is a big challenge, the process of getting approvals for property is a nightmare from what I hear. It’s tedious and time-consuming.

Q. What kind of growth are you witnessing in the housing sector now?

See, I can’t get into quarterly numbers, but if you look at December 2013, where the numbers are public, our individual loan book increased by 27 percent, which is much higher than what our targets have been. When we talked to investors we’ve always talked of a growth of 18-20 percent. We never talked of one quarter or one year, we talked of a sustained period of time. And I continue to believe that over a sustained period of time, growth of that magnitude would happen. But the base is high. It’s not small.

Q. You mentioned that there could be slight corrections in some quarters. But what about a time correction? Prices may not rise for three years, for instance…

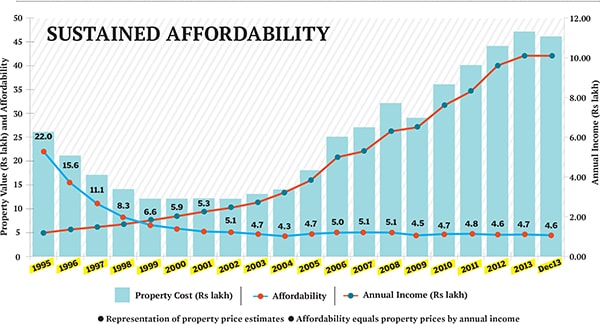

Practically, we’ve never really seen a time correction…In 1995-97 maybe there was a slight correction. There were some reasons for that, like the Urban Land Ceiling Act got repealed, a lot of property had been bought in 1992-95 by non-resident Indians largely living in Hong Kong which was moving to the Chinese. Then it picked up.

Q. On another front, there has been significant growth in incomes over the past few years and yet, because of the prices, affordability remains more or less constant over time…

Affordability on a pan-India basis is all right. But if you look at it specific to Mumbai or Delhi, then it’s never going to be affordable. How will it ever happen? Where’s the land to construct on? Land prices just keep going through the roof.

Q. In the wake of the slowdown, you don’t see a price correction?

You can see, as I said, a quarter or two here and there, where prices have come down or in some pockets where prices had run up a lot, but my personal view—and this remains unchanged for more than a decade—is you will never see a sustained drop in prices.

Q. What about a slowdown in segments, say, like luxury housing; housing above Rs 10 crore or so?

If you’re looking at the luxury segment, I don’t know whether Rs 10 crore is a luxury anymore (laughs).

Q. Fine, let’s up it to Rs 20 crore…

The luxury segment is a bit more market oriented. So it’s a little more a function of how the economy is shaping up and things like that. So if you take the last two-three years, the economy has slowed down and so you’d logically expect prices to have come off a little bit. But we’re not seeing that. Even today we should see prices come down in the luxury segment, but that’s not really happening.

Q. But the velocity of sales has slowed down…

I don’t know where all this data is coming from. If you look at Mumbai, it used to be the third largest centre for business three quarters ago. In the last month, for March, Mumbai was second, and it pipped Chennai. It’s Delhi NCR which is at one, Mumbai is two, Chennai is three, Bangalore is four, Pune is at five. This is by way of new loans generated, new disbursements in the month.

But then, Mumbai for us is not Dadar or Parel or Mahalaxmi. It’s more the outskirts of the city now. So it’s Nalasopara, Mira Road, Virar, Boisar, beyond Thane.

Q. Your loans are typically in the Rs 30 lakh category, isn’t it?

Our average loan size for new loans given till December 2013 was Rs 21.9 lakh. If you take a 65 percent loan to value ratio and work it backwards, the property value would be about Rs 34-35 lakh all-India. Who are the ones borrowing from us? Our borrowers are end-users. People who are buying need houses to stay in.

Honestly, I don’t see that much of investor market or speculative market in property notwithstanding whatever you hear in the market. Maybe in some pockets in Bangalore or Gurgaon, but otherwise 99 percent of properties that are bought is because people have to stay in that house.

Let’s talk of interest rates: Do interest rates impact the decision of a person to buy a house? No, we don’t see that. If you take the last seven-eight years’ data, the growth has not been slower in a year where rates are higher and vice versa. We’ve seen no correlation at all, or very little correlation. There are two reasons for that. One is that there are tax benefits: So the interest you pay is tax-deductible, the principal is tax-deductible. The actual effective cost you pay is much lower than what the agreement rate is. The actual effective cost for someone who takes a Rs 20 lakh loan after you factor in the tax benefits is 5.1 percent. This is only at Rs 20 lakh. As the loan amount goes higher, the 5.1 percent will go higher because the tax benefits are in rupee terms and not linked to the amount of the loan. The tax benefits have increased over the years.

The other reason why interest rates don’t affect a person’s decision to buy a house that much is because you’re buying a house for your residence. It’s a one-time purchase you’re making, and if your family likes the house, if the house is good and it’s affordable in the context of your income, people are not going to avoid buying the house just because the interest rates are half a percent higher or lower. Also, there are floating rate products in the market. You get the benefit of it whenever rates come down.

Q. What are the trends you see in the pure luxury space?

See, the luxury segment is not a very big market from our perspective. Even in the overall market, the luxury segment is more talked about and gets more eyeballs and attention, but in terms of the number of luxury transactions compared to the overall number of transactions, it is really miniscule. Look at properties: How many properties are above Rs 10 crore and how many are less than Rs 10 crore? If you look at just the city of Mumbai, I am sure the ratio [of non-luxury to luxury] will be something like 95-5. If you look at it pan-India it would probably be 98-2 or 99-1. So that one or two percent draws a lot of attention but is not very relevant.

But in the luxury segment we have not seen prices come down.

Q. So real estate prices are slowdown inelastic?

Why is it slowdown-inelastic? One is the need for housing. So if you’ve been staying with your parents and now you’re married, you may look for your own house. The brother is also there…etc. [Even in the luxury segment] one would have expected some drop in prices but even that hasn’t happened.

Q. Is it because people in India have a lot of holding power? That’s what a lot of developers say.

I don’t know if that is true. Maybe it is true for some developers. But I know there are plenty of people who are calling. I personally get a number of calls from people who say they’re looking to buy something and for me to suggest something good at a good price. And these are luxury type apartments.

One other thing is, suppose you’re 35 and you’ve been living with your parents for a number of years. You need independence, your child is growing up, he or she needs his own space…so you need a house. If your budget is Rs 50 lakh, and you don’t get a three bedroom and five minutes walk from the station, you make a compromise and go in for one which is, say 20 minutes walk from the station. You may even go in for a smaller apartment, but you will still buy a house.

Q. Since 2006, a number of real estate funds have come into the market. Now everyone is getting into mezzanine debt. If developers are stressed, won’t the situation get exacerbated?

You see, the reason why mezzanine debt became popular is because of land purchases. The formal system does not finance the purchase. No bank or housing finance company is allowed to fund land purchases. So then where does a developer go? He either goes to a local moneylender who charges an exorbitant interest rate, an NBFC [non banking finance company] who will sell down his paper to an HNI investor or he has to go to a private equity fund. He doesn’t have a choice.

Q. If a number of developers are unable to pay back the 20 percent plus loans, don’t you see stress in the system over the next two-three years?

There will always be a couple of people here and there who will be in difficulty. That is true in any industry. But I don’t see it happening more to the developer community than to others. You take 2008-09, which is a classic example. There was a slowdown, interest rates were very high, nobody wanted to lend money to developers. Did you see a single failure? That time there was also a craze about land funding. A lot of them wanted to do IPOs and the land was given some crazy valuation by investment bankers. That enabled you to get a very high price when you went for an IPO. Then the crisis hit in 2008. But still people got over it. Now that phase is over. You don’t see people scrambling to buy land. And IPOs have stopped. There’s not been an IPO in the real estate sector for god knows how many years.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)