The Singhs of ACG Worldwide: Capsule czars

With their fraternal camaraderie and complementary skills, Ajit and Jasjit Singh built ACG Worldwide into a global, diversified pharma services giant; now as next gen takes charge, there's still room to grow

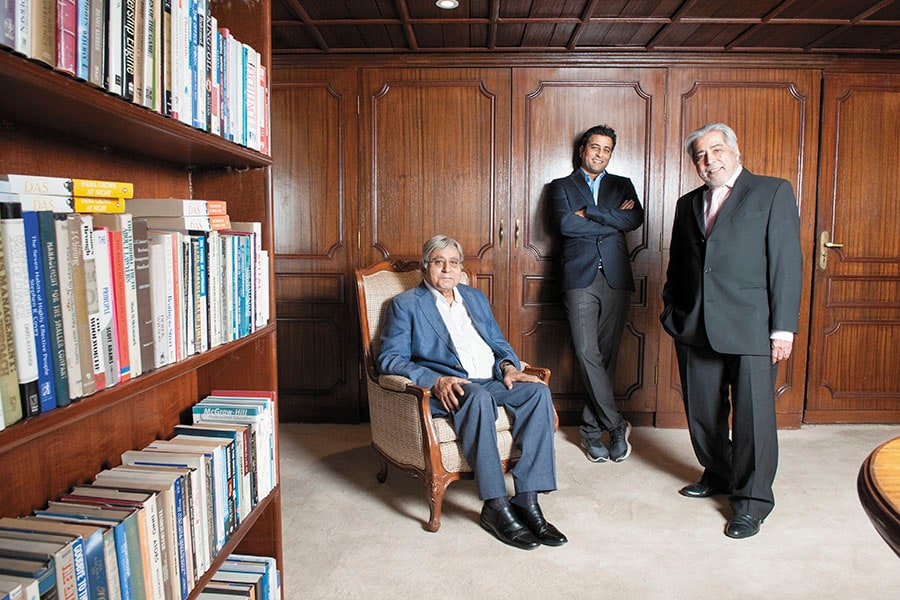

From left: Ajit Singh, ACG chairman; Karan Singh, its managing director and Jasjit Singh, who is vice chairman

From left: Ajit Singh, ACG chairman; Karan Singh, its managing director and Jasjit Singh, who is vice chairmanIn the ’70s, when trade union leader Datta Samant was throwing a spanner in the works of Mumbai’s industries by organising workers’ strikes and protests, two young businessmen were faced with the dilemma of downsizing the staff at their factory without risking an agitation.

Brothers Ajit and Jasjit Singh—whose family business Associated Capsules Group (now ACG Worldwide) made hard gelatin capsule shells for pharmaceutical companies—decided to mitigate Samant’s threat in a unique way. They had plans to bring about greater automation at their factory in the Mumbai suburb of Kandivali. “We needed to explain to him [Samant] that if we don’t reduce our workforce, foreign competition [via imports] would kill us,” says Ajit.

Recounting the tale on a January afternoon from his wood-panelled office (called the ‘War Room’) overlooking the Arabian Sea at Nariman Point, Ajit, ACG’s chairman, explains how the brothers observed that during normal business hours, hundreds of industrialists made a beeline for Samant’s office. By the time he had given each of them a five-minute audience, he would be in a filthy mood. To catch Samant in a fresh state of mind, the brothers decided to wait outside his office at 5 am. The plan worked as Samant greeted them warmly when he walked in.

This quality of the Singhs, to think out-of-the-box and face challenges and opportunities with speed and agility, has propelled ACG into becoming one of the largest suppliers of integrated manufacturing solutions for the pharma sector.

Founded in 1964, the $500-million ACG (expected turnover for FY18) is the world’s second largest manufacturer of empty hard-shell capsules, and also the third largest maker of films and foils used for blister packaging of medicines.

The company’s other verticals include an engineering business, which makes machines used for granulation, tablet manufacturing, tooling, encapsulation and end-to-end packaging, and an inspection vertical through which ACG implements track-and-trace solutions. The company enjoys healthy profitability and operates at an Ebitda (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) margin of around 20 percent (implying an annual Ebitda of around $100 million).

ACG, which employs 4,500-odd people, supplies its products and services to over 100 countries, has seven manufacturing sites across India, Croatia and Brazil, and an R&D centre in Mumbai. ACG’s clientele includes renowned Indian and international pharma companies—AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Abbott, Biocon, Lupin, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Johnson & Johnson, Mylan and Teva.

More importantly, the company’s growth mirrors the evolution of the Indian pharmaceutical industry. In a regulatory environment where prices were capped, the only way pharma companies could maximise profitability was through cost-cutting. For this, drug makers needed partners like ACG that also believed in frugality.

The brothers can also attribute their success to their complementary nature. Jasjit, 75, is an engineer, while Ajit, a year older, is involved with the management aspects of the business. Their bonhomie is difficult to miss, even after just five minutes into a conversation. Jasjit jovially forewarns that his version of ACG’s history will be starkly different from that of Ajit’s while the latter quips that the two better write separate autobiographies.

But it turns out that they are on the same page.

Ajit’s and Jasjit’s father, Daljit Dharam Singh, was a serial entrepreneur whose businesses included stone quarries, the production of vinyl records, and synthetic paint manufacturing; none are currently operational.

It was Daljit Singh who cut the first turf for the capsule shell business by securing an industrial licence. It was the last business he dabbled in before he passed away and left behind a mountain of debt for his sons to deal with.

Ajit, an MBA from the Harvard Business School, and Jasjit, an engineer from the University of London, were non-resident Indians at the time. After their father’s demise, they returned to India to take over the reins of the business.

“The business would have closed down in six months under the weight of the debt burden,” says Jasjit. “He [Daljit Singh] was borrowing money from moneylenders to pay salaries since he believed that his staff must be paid first. We, too, continued to borrow to keep paying salaries and then the business started stabilising.”

ACG is the world’s second largest manufacturer of empty hard-shell capsules.

ACG is the world’s second largest manufacturer of empty hard-shell capsules. In its first year, ACG reported a turnover of ₹9 lakh and a loss of an equal amount, Jasjit says. In the second year, revenues increased to ₹17 lakh and the company achieved breakeven. At present, ACG is a zero-debt company on a net level.

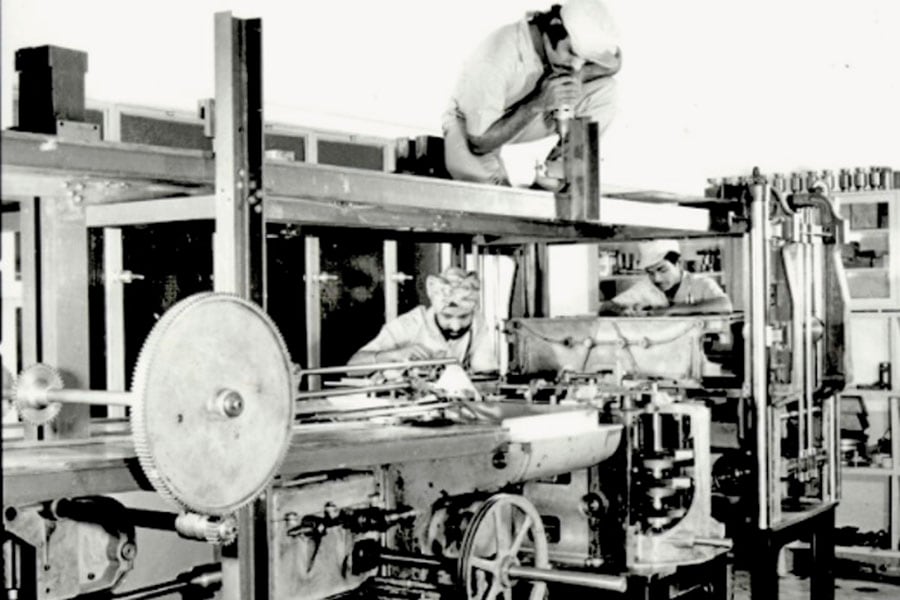

Ajit says the first 7-8 years were extremely challenging. The technical know-how to manufacture machines that could make capsule shells, and fill them with the desired drug, wasn’t available in India then and importing it was not feasible. So Jasjit had to replicate the specifications of the machines used abroad.

They first operated out of a friend’s garage and then moved into a shared foundry in Kandivali before their first full-scale factory was up and running. “There was a lot of trial and error in the first few years as we constantly tried to improve the quality of the capsule shells. This continued till we made a breakthrough in the seventh or eighth year,” says Ajit.

To further expand ACG’s playing field, Ajit sensed the need for blister packing, using films and foils, among drug makers. Jasjit got down to work again by developing machines that produced blister packs that met global quality standards at twice the rate. It wasn’t long before pharma companies began seeing the economic benefits of partnering with ACG instead of importing these products.

“India is a place where people are ready to try something new, if the price is right,” says Jasjit. “They didn’t mind importing a machine for ₹1.5 crore in those days. But if I could offer them the same product for ₹10 lakh, they were willing to take the risk.”

PB Nair, senior vice president and head of the global formulations manufacturing business at Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, credits ACG with helping the Indian pharma industry save precious foreign exchange, which it would have otherwise spent on imported capsule shells and machines. Nair says 75-80 percent of the Indian pharma industries’ need for capsules is being serviced by ACG currently.

“While most family-owned pharma services companies in India have focussed on a limited number of products or services, ACG has invested significantly to diversify its offerings,” says Nair. “They hire the best talent and empower them to create world-class products through R&D.”

Diversification apart, ACG’s impressive topline growth (recording over 20 percent each year over the last four decades) would not have come about by catering to domestic pharma companies alone.

Ajit’s strategy was to first go into a new market overseas, seed it through business development efforts and export from India. Once ACG cornered a decent share of the market, it then looked at setting up manufacturing operations there.

Along the way, ACG made acquisitions like Lukaps (2007), which has a capsule shell manufacturing plant in Croatia and services the European market and Nova Nordeplast, a Brazilian company that makes films and foils (2017). Currently, half of ACG’s turnover comes from its international business (including exports and global manufacturing).

But even as ACG grew in size and stature, it never sacrificed its spirit of customer service, and that is what has led pharma’s marquee names to repose their faith in it. Alok Ghosh, president of technical operations at Lupin, says the executives at ACG continuously listen to customer feedback and improve their services. “They are one of the few companies that will give you a new machine worth ₹2-3 crore for a free trial and take it back if you are not happy with it,” says Ghosh. “The average cost of their equipment is a quarter of the price that needs to be paid to import the same machines.”

Over the last five decades, ACG has shown remarkable progress, and achieved all of this while remaining private. The Singh family entirely owns ACG and the company has thus far managed to finance its growth through internal accruals and debt, without having to resort to raising external equity.

And how did they manage this? Ajit offers a concise answer: “Through very careful management of funds and high-quality project execution economically.” Jasjit says barring a couple of years, ACG chose to reinvest its entire profits into growing the business, rather than paying out dividends to the promoters.

Did the brothers ever succumb to the temptation of cashing out in part and realising the material fruit of their labour? “The wealth is growing at a rate of 20-25 percent each year. If we take it out, where else will we get such returns? Many wealth managers come to us and pitch investment ideas. I show them the calculations and ask them to guarantee better returns. That’s the last that I see of them,” says Jasjit.

Ajit admits that ACG has been able to generate enough surplus to keep the business growing because it chose to grow a “little slower than it could have”. The company always had cash and could have accelerated its international manufacturing plans earlier, if it chose to, he adds.

But now, such measured steps seem to be giving way to youthful aggression and ambition. As one generation of entrepreneurs passes the baton to the next, the wheels are turning faster. Karan Singh, 37, Jasjit’s son, is currently the chief architect of the company’s future as ACG’s managing director.

Karan, who joined the family business in 2002, points out that while ACG earns 50 percent of its turnover from abroad, 90 percent of its manufacturing still happens in India. “To be successful in the pharma business, you have to be local and branch out into different parts of the world,” explains Karan, a graduate in organisational psychology from the University of Michigan and an MBA from Harvard Business School.

As a result, ACG is now in the middle of executing a $150 million capital expenditure programme, including expansion of existing facilities in Croatia and Brazil, as well as greenfield ventures and/or acquisitions in Southeast Asia and North America. The expansion that is expected to be complete in the next fiscal will boost ACG’s production capacity by 20 percent and add another 30 percent to its topline over the next two to three years.

Selwyn Noronha, group chief executive of the capsules business at ACG, who joined the company 37 years ago as a trainee engineer, points out that when Ajit and Jasjit were starting out, their risk appetite was tempered by the fact that they were trying to stabilise a new business after paying off debts. “The business required continuous funds. So the idea was to earn and spend when it came to expansion,” says Noronha. “Karan comes with the mindset of leveraging the balance sheet for expansion and growing the business internationally and investing in future growth areas.”

Karan is also bullish on future business opportunities, stemming from new technology. ACG has coders on its payroll, entrusted with developing new technologies based on the convergence of Artificial Intelligence, virtual reality (VR) and Internet of Things. For instance, the company has developed a set of VR goggles. When a customer wears them and looks at a machine, he can see a menu superimposed on the equipment. From there, the customer can pick and choose what he wants to do, which includes preventive maintenance. This enhances productivity and reduces dependence on external customer support. In 2017, ACG acquired another company in Croatia called In2trace, a startup that had proprietary technology that complemented ACG’s own offering in the track-and-trace business.

Karan, who is fond of playing basketball and driving fast cars (he has an Aston Martin DB11 in the garage of his family’s sea-facing bungalow on Bandra Bandstand), sees a plethora of opportunities for ACG to tap into. One option is to branch out of pharma and get into the food and consumer goods packaging; the other is to expand its offerings in the pharma space to include liquid drugs (such as injectibles, ampules and vials). Another is to get into contract manufacturing of select products such as vitamins, ayurvedic products and sports medicines, where it doesn’t directly compete with its customers (the company already has a contract manufacturing unit in Pune that Karan started in 2017, which has exhausted its capacity). Manufacturing raw materials needed to make capsules, such as gelatin and cellulose, is another area that ACG is looking at.

ACG supplies its products and services to over 100 countries. It also has an R&D centre in Mumbai

The rapid pace of growth has also meant that ACG has had to bring in professional talent from outside. And the talent has come not only from India. ACG has three expatriates in its 12-member senior leadership team, and 20 percent of its workforce is stationed outside India. As ACG continues to expand globally, Karan expects 40-60 percent of the company’s talent pool to reside outside India over the next three to five years.

One of the expatriates to join ACG in July 2017 was Richard Stedman, group chief executive of the engineering business at ACG. Stedman, a South African who later migrated to Australia, has worked for 39 years across these two countries and New Zealand and Singapore. Now based in Mumbai, he admits that after having worked for multinational corporations all his life, he had his apprehensions about joining an Indian family-run enterprise. “But I found ACG to be professionally run and remarkably sophisticated,” says Stedman. “When I arrived, Karan was quick to step back and hand over control. Over time, our monthly meetings have become quarterly reviews. The family is astute and understands the changing dynamics of the business. They wanted an expat to bring in a different perspective to the business and interact with clients around the world.”

One thing is certain: ACG is not content being the world’s second largest capsule shell maker. It wants to be the largest. “There are only five to seven companies in the world that have understood how to make [shells for] capsules in large quantities. We are growing in double digits and the number one player [US-based Capsugel] is growing at 2-3 percent. So it is not long before we catch up with them,” says Ajit. “That is Karan’s challenge.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X