Science's Second Coming to India

There is enough evidence on the ground to indicate that the innovation eco-system has vastly improved in the country. India is ready for a renaissance in innovation

A couple of weeks ago, some of us got into an interesting conversation with Howard Gardner, who was on a visit to India to deliver a series of lectures. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential psychologists in the world today. Author of 25 books that have been translated into 28 languages and best known for his theory of multiple intelligences, in 1995, he mounted a study that lasted until 2006 and involved 1,000 American journalists and geneticists. The question he was seeking to answer was an intriguing one. Why are journalists an unhappy lot while geneticists a happy bunch?

The answer was interesting. Journalists, he concluded, were idealistic individuals who got into the profession and hoped their work would change the world. Once they were in though, they figured, the business was run by people whose interests were focussed almost entirely on the bottom line. The real world was out of sync with everything they had imagined it to be.

Geneticists, on the other hand, as much idealists as journalists are, had everything going for them. The Human Genome Project was the Holy Grail that needed to be cracked. The geneticists therefore had to focus on nothing but their work; the American government was solidly backing every gamble the geneticists wanted to take; venture capital funding was chasing them in droves because they knew as well the Holy Grail needed to be cracked, and the only way it could be was by supporting the best minds America had. And if need be, do what it takes to get the best talent from across the world.

Eventually, the project was completed in 2003 and the euphoria lasted a while. Over time though, it started to diminish and, much like in journalism, conflicts began to erupt between the various stakeholders. The geneticist’s idealism now finds itself at odds with an eco-system starved for funds and hell bent on maximising profits. As Gardner wryly says, “It is difficult to do good work that is both technically excellent and carried out in an ethical way when a market is down.” To that extent, it wouldn’t be way off the mark to argue the golden age of American science is waning. Of course, as Gardner quickly adds, “All misalignments are temporary.” But in one man’s misery, even if it be temporary, lies another man’s fortune.

Which is why, policy makers in India, which for decades has exported its finest minds to countries like the US, are wringing their hands with delight. By all accounts, the wheels have been set in motion to win back some of the finest minds of Indian origin to align forces with their country of origin—either by coming back home, or by helping set up the framework that will stimulate a renaissance.

To get a sense of the minds now being wooed by the government and businesses in India, starting Page 70, we’ve put together a list of 18 scientists of Indian origin who’ve had enormous impact on the disciplines they operate in. It includes areas as diverse as nano particles to treat cancer, global warming, landmark discoveries on diseases until now thought of as untreatable, biometrics and pattern recognition, regenerative medicine, and technologies we now consider ubiquitous like the humble USB port.

Bits to Torrents

G. Rangarajan is already preparing for his visit to Stanford three months from now. A professor of mathematics at the Indian Institute of Science, he will descend on the university’s campus as part of a delegation of directors from some of the leading institutes that include the IITs, the National Institute of Technology and the Indian Statistical Institute. This crack team intends to address an audience of academics, mostly of Indian origin, and urge them to consider a career in research back home.

Rangarajan, who is coordinating the visit, has a deck of slides ready, which offer a graphic picture of academic life in India. It even gets down to brass tacks like salary structures, what pay hikes to expect, consulting opportunities available, startup grants on offer and even domestic help—a carrot unavailable in the West.

“We have an acute shortage of these professionals, especially in computer science. So we decided on these road shows to spread the word that life here isn’t bad,” says Rangarajan. To buttress his case, he argues that adjusted for purchasing power parity, a full professor’s salary in the US at $12,500, is on par with the $2,900 on offer in India. This isn’t the first time government-backed institutes have been on such a man hunt. Two years ago, a similar exercise was conducted at Brown University in the US and a handful of researchers bit the bait.

The department of science and technology stepped up its initiative last November. T. Ramasami, the secretary who looks after the department, was able to collect at least 330-odd resumes from leading universities in the US. “I have sent the CVs to various institutions for consideration. In the 12th Plan, my department will give a start up research grant of Rs. 50 lakh each to 1,000 people who return to India. This will be over the salary or research facilities that the hiring institution provides,” he says.

Last year, M.K. Bhan, a senior bureaucrat in the department of bio-technology, was able to attract 300 researchers back to India. All put together, over the last three to four years, he’s managed to attract 800 people back to various Indian institutions.

But getting the brightest talent is just one way to catalyse innovation. It won’t work until the rest of the eco-system is geared to support the influx. Countries like Korea, China, Singapore and Malaysia figured that more than 10 years ago and are now beginning to reap the dividends.

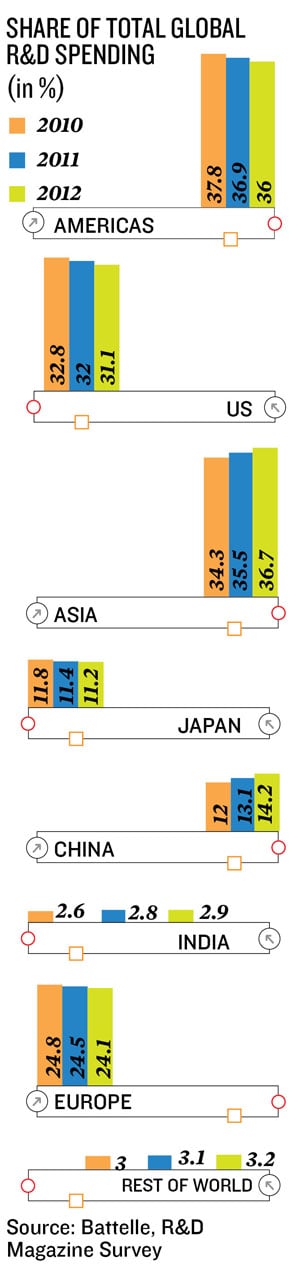

That explains why on January 3 this year, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh announced that by the end of the 12th Plan in 2017, India would more than double its annual research and development (R&D) budget from $3 billion in 2011 to $8 billion, or 2 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP)—a measure of the total value of all the goods and services produced in a country annually. It now stands less than 1 percent as opposed to China’s 1.6 percent.

But this is only the first step. “Research can convert money into knowledge,” points out R.A. Mashelkar, former director at CSIR and now president of the Global Research Alliance. “But you need innovation to convert knowledge into money,” he says. And this, he says, is where India has faltered historically.

In the post World War II era, no other nation could innovate as well as America. It put into place a great system of universities, enabled intellectual property rights, and promoted commercialisation. “The US is probably the only example of government-funded research that becomes a company or even an industry that creates wealth and jobs,” points out Pradeep Khosla, dean of engineering at Carnegie Mellon University. Understandably, many nations have tried to emulate it, but haven’t quite made the mark.

The financial meltdown in 2008 changed much of that. Since then, the famed American model has begun to develop cracks. Budgets have shrunk; the focus of research has narrowed, and policy makers now want more bang out of every buck spent. It is a view supported by A. Raghuram, head, department of mathematics at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Pune. After 10 years at Oklahoma State University, he moved to IISER in December. What swung the decision for Raghuram: An overall change in the scientific community and the possibility of making a “fundamental difference”.

Sensing the opportunity, the Indian government is pushing ahead with a range of new policies aimed at not just attracting its brains trust in the West—but also filling voids in the innovation infrastructure.

Taking a leaf out of the Singapore experience, in the 12th Plan, Ramasamy proposes to create 1,000 doctoral and 250 post-doctoral fellowships in foreign universities, where his department provides monetary support to Indian candidates selected by universities such as MIT, Caltech, Stanford and others. The hypothesis: Many of them will come back after their doctoral studies.

Bold ideas that require long gestation periods will also get government funding. The evidence is on the ground:

- In 2010, the department of science and technology became a lead investor in the Nasscom-promoted India Innovation Fund.

- In November last year, the Cabinet approved the Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council, which will fund science-based ideas from its 12th Plan budget.

- The National Policy on Electronics, 2011, now in its final stages of approval, will have an Electronics Innovation Fund.

- In early February, the government approved Preferential Market Access in public procurement for locally developed and designed products, a policy that Israel has effectively used to build its high-tech industry.

- A group under the Planning Commission is evaluating attractive “exit options” for investors who fund risky, innovative ventures—something that doesn’t exist today.

- But problems exist.

Ground realities

Ground realities

After a bold biomedical sciences initiative in 2000, Singapore decided to attract 1,000 Singaporeans in 10 years. Today, half of 2,500 researchers of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*Star), the lead agency fostering scientific research and talent creation, come from 60 countries. “These investments have brought substantial returns for Singapore. Between 2000 and 2010, biomedical manufacturing output has almost quadrupled and now accounts for about 8.6 percent of our manufacturing output” says A*STAR Chairman Lim Poh Chuan.

In 2006, when China announced its 15-year plan to make science and technology the backbone of future economic growth, it first introduced sweeping reforms to its educational institutions. The message was clear: Don’t follow the leader. Innovate.

But, laments DBT secretary Bhan, India’s institutional leadership “doesn’t push for excellence”. Our institutions train PhDs for faculty positions, not for innovation. To start with, he now has the approval of the Planning Commission to build full-fledged centres that will operate inter disciplinary centres. Until now, only programmes have existed like the ones between the All India Institute of Medical Sciences and IIT Delhi to develop new medical devices.

Fact of the matter is, older institutions may find it tough to adapt to this new scheme of things. Ramasamy admits institutional mechanisms need to change. But he doesn’t approve of radical reforms, least of all the Chinese-way. “China is north of Himalayas and India is south of Himalayas. We have a difference in polarity: They prioritise economic freedom over political freedom. We prioritise political freedom over economic freedom,” he says.

Be that as it may, in the short term, indecision and delays are hurting the cause. It’s the lack of speed in implementing policies that is hurting India says Mashelkar. He cites the example of the all-composite trainer aircraft from National Aerospace Laboratories (NAL), which first took to the skies in May 1998. But it was only 13 years after Mahindra & Mahindra (M&M) got into a joint venture with NAL that the venture was commercialised.

But that isn’t to say business has played its role to the hilt. Until now, very few Indian companies, other than those in pharmaceuticals and automotive, have focussed on research-based innovation. “We are not focussing enough on this as India Inc. We are happy with the CAD/CAM work at $9 an hour, compared to $30 that people have to pay elsewhere in the world,” says Pawan Goenka of M&M.

Many don’t have internal capabilities and some others don’t show the willingness to spend on R&D; they believe it should come “free”, says Battelle India head Shalendra Porwal. A contract research agency, Battelle India is recognised by the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research.

In December 2010, Ratan Tata, who presides over the IISc Court, the topmost decision-making body at the institute, said it is not doing enough research of greater global relevance. “If I look back on what I have been trying to say in a very polite and in a very careful manner, it has been my perception that this institute, which is a great institute....has not perhaps changed as much as one would like to see. ...I have mentioned that we should perhaps be looking at greater change, research of greater global relevance and I have used my words carefully,” Tata reportedly told the Court.

Changing Times

A “big fan” of research-driven innovation, veteran venture capitalist Vinod Khosla, who has made a living hunting for radical ideas that he can then fund and build businesses out of, suggests getting top notch talent to either start projects or mentor people. “If you set up centres of excellence and put thought leadership in research, great product ideas will flow from it. China has done that fairly well.”

Many critical areas that need research over the next 20 years don’t need extraordinary infrastructure he says. “What you need is culture and role models. Once people are there, things will happen. Attracting world class researchers will attract business and investors,” he says. The good news is there is consensus among decision makers around this thought. New institutions coming up, and some of the old ones as well, are looking at good scientists, regardless of their areas of expertise. This is in contrast to the US, which today has specific requirements, says Collins Assisi, a neuroscientist at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California.

Assisi, who has decided to relocate to India, has interviewed at a few places, including IISER Pune. “I really liked their commitment to teaching,” he says. It’s clear they are not just coaching students to be scientists, but to apply their work to life and go into government, management or industry. “That’s a refreshing change from what you see in typical graduate teaching in the US or older Indian institutions,” he adds.

Rahul Siddharthan, a computational biologist at the Institute of Mathematical Sciences in Chennai, reckons India ought not to restrict itself only to people of Indian origin. The economic climate has many foreigners, particularly the Europeans, interested in India today. The recent relaxation of rules on work visas by P. Chidambaram (for people earning more than $25,000/year) should be used to get good talent.

The thought gains currency when you factor in that copy-the-West used to be the norm in earlier days. But in a globalised world where everybody knows what the other one is doing, you’re better placed as an innovator than a copier, says Supratik Guha, the director of physical sciences at IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Centre in New York.

It is a lesson inStem, at NCBS has taken to heart. Since the science of stem cells is far from definitive, along with applied work in cardiac hypertrophy and cancer, inStem has taken a new approach to study basic biology. It is developing Hydra and Plenarium as model systems to study biology. “This is something you’d never be able to do in the West today [because the disease relevance is not apparent today, but will be only in 10-15 years],” says dean S. Ramaswamy.

Removed from the world of academia, state-run power equipment maker BHEL increased R&D investment 21 percent last year. Private companies like L&T are upping the ante on application development. M&M has moved 1,200 people to its research centre in Chennai and the number will increase to 2,000 this year. Most of its new products are being designed in-house. Much the same can be said of Tata Motors.

A lot of development work is happening, says V. Sumantran, executive vice-chairman of Ashok Leyland and a former member of the PM’s Scientific Advisory Council. “Research is limited to small pockets. But a lot of multi-national companies are beginning to tap into them,” he says.

But in the end, from a holistic prism, quite clearly, there is enough evidence to indicate that all the “trustees” needed to kick start the innovation eco-system in India—as Gardner would say—are aligned.

The government seems to be getting its act together; businesses where the money lies to fund these projects seem keen; and most importantly, the brains that can power these projects are buying into the promise as the following pages will demonstrate. It would only be fair to assume therefore the golden age of Indian innovation has just about begun.

(Additional reporting by Cuckoo Paul and Ashish Mishra)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)