Overcoming resistance to digital change

Leaders need to see the ways in which digital change is different

Middle managers in the organisation seems to be particularly troubled by digital transformation

Middle managers in the organisation seems to be particularly troubled by digital transformation

Image: Shutterstock

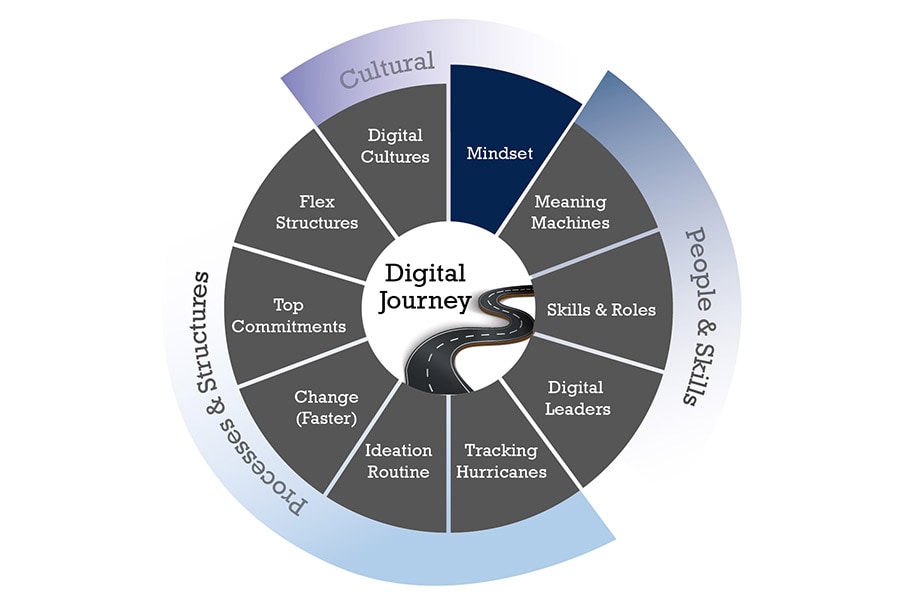

This is the fourth article in our special series on the Digital Journey.

Going digital requires a lot of change management, and perhaps more time and energy is spent here than on anything else. Why would that be the case? As we’ve discussed in the earlier parts of this series, organisations on the digital journey may need to rethink core roles and processes. The result is that as much as companies may aim for external disruption in these changes, there is also likely to be severe internal disruption. This is why “cool” digital ideas may not seem so cool or friendly to internal stakeholders. In fact, they may be very hostile. Also, these changes may involve deeper learning curves, with initial losses of efficiency and/or effectiveness, as the core system is in transition (i.e. things are likely to get worse first before they get better, and the trough potentially deeper than other sorts of change). Finally, the integration needs of digitising companies may be greater than other forms of change, with more unintended consequences of digital changes (i.e. knock-on effects to other systems and processes or partners).

For these reasons, the journey may be a bumpy one. The pace and extent of change can unsettle staff and manifest itself in the form of resistance, and according to our interviews with digitising companies, that resistance can be especially strong among middle managers. This level in the organisation seems to be particularly troubled by digital transformation. But this begs the question of why? Is the reasoning fairly obvious (digitisation as a threat) or is more going on? We found, in fact, three factors.

The first reason we came across was certainly the perceived threat of the change. For example, one participant explained that the shift for organisations to be driven by data and analytics is a direct assault on middle managers sense of control. “You're basically saying your customer is your expert now and your customer knows what's best. Maybe what [managers] thought was the right thing to do doesn't matter as much anymore,” said one. There is also the threat of learning new technologies.

The second reason is seemingly obvious but underappreciated: time. Time to learn, to set up new routines or collaborate more broadly is now of the essence. But the lives of most middle managers are filled with meetings, reports and a bureaucracy that they need to feed on a daily basis. Who has time for retooling? They are also shackled to metrics and legacy incentives that focus them on near-term results or legacy processes. This leaves middle management with little time to get up to speed with other organisational initiatives. One interviewee told us “we don’t really have a reward system for things like that [involvement in digital initiatives]”. Ultimately, meeting their official targets is what they are appraised on. “It’s a time and a priority issue,” they continued.

The third is value. Middle management may resist for the simple reason that a digital idea or initiative lacks value. Organisations can certainly be swept up in what appear to be game-changing new technologies that might not become big hits. Therefore, digital leaders need to be careful not to confuse personal threat and rigidity “resistance” with honest “questioning” of the value proposition behind a new digital initiative.

The change agent’s to do list

As we established in our interviews, not all middle managers are driven by purely self-protection. Neither are they clueless about the importance of things digital. It is likely that their personal lives are filled with an abundance of digital technologies, so they understand the potential.

So what should change agents do? Our interviews with executives actively involved in shaping the digital future of their companies revealed three strategies they could employ.

First, create a sense of opportunity, not only threat. One interviewee told us that what middle managers are looking for from their leaders is a “clearly established sense of what you’re trying to achieve”. They want clarity from their leadership to fully understand the strategy and absorb the changes to see how they can apply their skillsets or learn what needs to be learned.

The same participant continued, “What can happen within digital is that because there’s so much uncertainty, you don’t pay enough attention to your strategy, what are you really trying to achieve and how do we innovate within that.”

Second, create a narrative to educate. Constant education is essential to digitisation, which means digital leaders need to get into the corridors, lunch rooms, meeting areas, virtual chatrooms and engage people. The importance of engagement cannot be underestimated as far as one interviewee was concerned: “Within the last 12 months, I think we achieved a lot in terms of probably 50 percent of the middle management is now accepting what we are doing…They say ‘okay, we understand what they are doing. We understand how they are doing it’. We are also…taking people from the middle management and saying ‘okay, you are responsible for managing the investment into this and that.’”

Education may, in fact, need to go further. Firms should consider systematic efforts (time and resources) to help middle managers get up to speed on new digital technologies and methods. This does not mean turning a middle manager into an expert in data analytics, but some training in specific skills may be valuable and perfectly adequate. Unless the education sector can quickly produce an overabundance of new talent with such digital skills (which seems unlikely), some retraining may be necessary.

Finally, resistance may not fade away completely unless digitalisation activities are taken seriously and allocated real power and status. Leaders, therefore, need to make sure that digital roles and structures have the power to do their work and push the organisation along, not just pull.

“In the past, the digital leaders were not as important as the [core business] leaders and we are now better [positioned] in the structure and have more power. This is one important part,” said one interviewee.

In summary, our interviews suggest that managing digital change requires more appreciation of integration issues and internal disruption consequences, and the clear building of expectations. Managers need to understand exactly why people resist (fear, but also a lack of time and recognition, and serious questions about value) and address their worries accordingly. Finally, we need to think seriously about retooling methods for middle managers.

Charles Galunic is a Professor of Organisational Behaviour and the Aviva Chaired Professor of Leadership and Responsibility at INSEAD.

[This article is republished courtesy of INSEAD Knowledge, the portal to the latest business insights and views of The Business School of the World. Copyright INSEAD 2024]