The strategic science of delayed compliance

No company is above the law, but some firms are allowed much more time in complying with it.

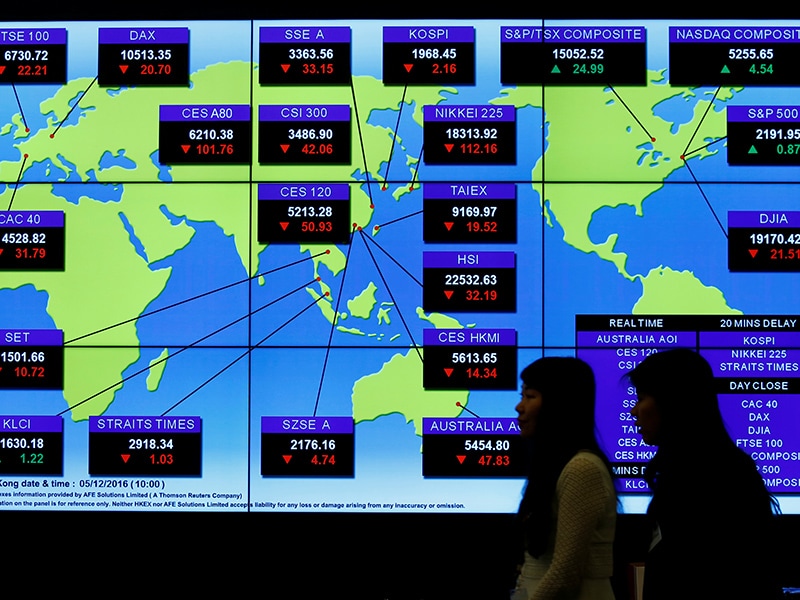

Image: Bobby Yip / Reuters

Obeying the law is non-negotiable, theoretically. The very existence of the compliance profession, however, implies that the reality is far more complex. Even more intriguing is the fact that, despite having splashed out on compliance like never before post-2008, banks in the United States and Europe had to pay US$65 billion in fines in 2014 alone. Many of the 2014 penalties pertained to violations committed well after the financial crisis by institutions deemed “too big to fail”. Financial behemoths apparently can afford to take a more wayward path to full compliance.

The financial sector is not unique in this respect. Even public organisations have been known to drag their feet on compliance, sometimes spectacularly – as in the early 20th century when municipalities in the U.S. delayed adopting civil service reform for more than 35 years.

How malleable is a compliance timetable in reality? In a recent paper in the Journal of Management, Cyndi Man Zhang of Singapore Management University and I find that even in China, where the central government is known to be strict, some companies were able to delay without consequences. This wasn’t due to haphazard oversight; the procrastinating firms had key features in common.

Split-share ownership

In 2005, Beijing launched sweeping stock market reforms aimed at advancing the transition from state socialism to market capitalism. The government mandated that listed firms end the practice of split-share ownership – reserving a large volume of shares for state actors and “legal persons” – which was linked to ineffective corporate governance and hemmed in economic development. Publicly tradeable shares were generally more expensive yet did not confer additional control over company decisions.

The central government viewed the reform package as essential to their privatisation plans, as evidenced by repeated “encouragement sessions” held in every province where recalcitrant firms were urged by regulatory agents to fall in line. Firms with a large proportion of non-tradable shares had good reasons to want to delay, as early adopters of previous market reforms had experienced steep share price decline. Still, the heavy state pressure garnered an 80 percent adoption rate within 15 months of the announcement of the reforms.

[This article is republished courtesy of INSEAD Knowledge, the portal to the latest business insights and views of The Business School of the World. Copyright INSEAD 2024]