The tension-filled world of luxury consumption

Recent research highlights how luxury consumers are pulled in different, often contradicting directions

Image: Shutterstock

Image: ShutterstockLuxury’s purpose used to be straightforward enough: to power dreams by creating social distance between the elite and the rest. For a few hundred years, this role was even bolstered by sumptuary laws in Europe and Asia that forbid the bourgeoisie to dress like aristocrats. Luxury consumption was the right, privilege and perhaps even the duty of the wealthy. But barriers to luxury fell progressively, until it was described as “the ordinary consumption of extraordinary people and the extraordinary consumption of ordinary people”.

This multiplication of consumers and the increasingly easy access to luxury through digital technologies is not without its headaches for luxury brands. How can they convince the wealthy to continue buying such products when regular people partake too?

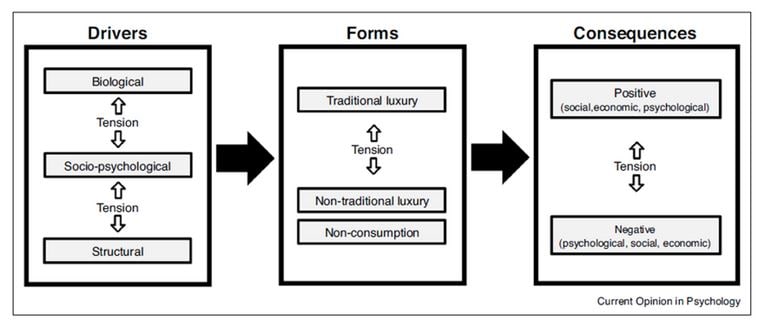

In a review of the latest advances in the psychology of luxury consumption, SungJin Jung, Nailya Ordabeya and I synthesised about ten years of research across the field. We found a common thread: the idea that the drivers, forms and consequences of luxury consumption – all three dynamic elements of purchases – involve tensions requiring great finesse on the part of luxury brands as they try to approach, communicate with, and ultimately retain clients.

Drivers

Our analysis of the drivers fuelling the desire for luxury revealed this desire often stems from conflicting motives. At the heart of it is the need for status, a deeply ingrained and often unconscious force guiding thoughts, feelings and behaviour about luxury brands. For instance, recent research showed that administering testosterone – a known biological driver of rank-related behaviour in the animal kingdom – to men increased the subjects’ preference for luxury brands such as Calvin Klein, but did not help a non-luxury brand of a similar quality such as Levi’s.

Of course, the matter is not that simple. Take what researchers have dubbed the “Abercrombie & Fitch effect”. This fashion retailer used to position tall, shirtless hunks as “brand ambassadors” at the entrance of its stores. It was easy to assume that such a tactic would lure in female consumers and boost their spending. But research showed that it was male customers instead – especially shorter men or those with a high hand digit ratio indicative of low levels of testosterone – who purchased more expensive products in the presence of physically dominant male employees. These male consumers were particularly prone to buying items that featured large status-signalling logos.

[This article is republished courtesy of INSEAD Knowledge, the portal to the latest business insights and views of The Business School of the World. Copyright INSEAD 2024]