What entails investing in a brave new world

Much has altered over the last decade, and more change is in the offing. So, stick to companies whose business models are easy to understand, which generate healthy returns on capital employed and which have a steady revenue growth

Christmas is my favourite time of the year because it is a welcome break from the relentless grind of research and deal-making that defines the life of an Indian broker with clients spread across the world. It also gives me a week or so to reflect, and as I write this column over the break of 2014, my mind goes back to the Christmas of 2004.

Christmas is my favourite time of the year because it is a welcome break from the relentless grind of research and deal-making that defines the life of an Indian broker with clients spread across the world. It also gives me a week or so to reflect, and as I write this column over the break of 2014, my mind goes back to the Christmas of 2004.

During that vacation a decade ago, I had come to India to explore business opportunities for a stockbroker like me in the roaring Indian economy. The small equity research franchise that I had just co-founded in the United Kingdom was growing steadily in a British economy which, in turn, was growing at 3 percent in a world where the price of a barrel of Brent crude was $40. Alan Greenspan was still the revered chairman of the Federal Reserve and hence, by extension, the most powerful man in the world after the president of the United States, George Bush. America and Britain had supposedly found “weapons of mass destruction” in Iraq and, consequently, their guns were trained on that region.

In India, the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) had just won the general elections at the expense of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) and Manmohan Singh was celebrated on the cover of Western business magazines as the intellectual, complex problem-solving leader that many Western countries wished they had as their head of state. The NDA, with its discredited India Shining campaign behind it, was seen as a political coalition out of touch with the harsh ground realities of rural India. More importantly, with former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s health on the wane, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)—the leading party in the NDA —was seen as rudderless compared to UPA leader Sonia Gandhi’s socialist “inclusive” view of India’s developmental process.

More generally, in the context of emerging markets, the acronym Brics had become fashionable 10 years ago. Friends of mine who had been running ‘emerging markets’ money for a long time suddenly found that over the course of 2004 and 2005, the phone started ringing more often as investors dialled in the dollars into those regions and, more specifically, into China and India. One such friend in Hong Kong found his fund swelling from $100 million at the beginning of 2004 to $1 billion by the middle of 2005. On billboards near my office in London, Brics funds were advertised with over 3 percent management fees.

Presuming that my Indian surname automatically qualified me to manage money in India, headhunters used to call me to ask whether I would like to make a switch from stockbroking.

The Western press attributed this rising enthusiasm for emerging markets to the adoption by these economies of the ‘Washington Consensus’ ie, the World Bank/IMF prescribed recipe of fiscal discipline, low inflation and an open economy (both from a trade and capital flows perspective). Gurus such as Tom Friedman, Barton Biggs, Stephen Roach, Jim O’Neill and Jeffrey Sachs were held in high regard for being the high priests of this new dawn for emerging markets.

New Political Constructs

The instinctive tendency of most analysts is to study historical trends and extrapolate them into the future. However, as Thomas Kuhn explained in his book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), while the real world might change in a gradual manner, the intellectual constructs that we use to understand the world alter in a “non-linear” fashion. That is, when a fresh way to think about the world comes along, and if this new construct gives a more accurate depiction of reality, we abandon the old construct at a rapid pace.

A new generation of “strongmen politicians” with no Western baggage has risen to power

One example of this is Copernicus’s view that the solar system revolves around the Sun rather than, as Europeans believed until the 16th century, around our planet. In the space of less than half a century, Copernicus’s radical thought overturned centuries of conventional wisdom and became the accepted way of thinking. In a similar vein, 10 years on from 2004, we are now seeing the advent of a new way of thinking about emerging markets in general and India in particular.

The Decline of the West and the rise of Asia: The West’s economic decline relative to Asia’s economic vibrancy is making it less assertive in this great game of global jostling by “strongmen politicians”. The economically enfeebled Europeans are almost invisible in international affairs. The Americans, while more visible, are no longer as assertive as they once were, even in the face of major transgressions by other great powers.

Witness the way President Obama is dealing with Ukraine. All of this matters because as Financial Times wrote on December 5, 2014: “What these leaders do tell is that the multilateralist model of the second half of the 20th century is more likely to represent a historical interlude than a permanent shift in the nature of relations between states.

Globalisation is already in retreat. As the “strongmen” stride the stage, Kant is making way for Hobbes and multilateralism for great power politics. The West is about to relearn what it is like to live in a much rougher world.

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

The decline of Economics: Economic ideologies— both on the Left and the Right—have failed over the last 20 years as evidenced by a series of major economic crises in both emerging and emerged economies (think of the East Asian crises and that of Russia in the 1990s followed by the dotcom bust and then the Great Financial Crisis of 2008). As a result, hyper-nationalism—with a strong religious flavour—is the only prevailing ideology which sells across large numbers of people. Vladmir Putin in Russia, Recep Erdogan in Turkey and Narendra Modi in India are politicians from this school.

The rise of “strongmen politicians”: A new generation of “strongmen politicians” with little or no Western intellectual baggage has risen to power. Hypernationalists are now not only the prime leaders of key emerging economies, they are, in line with their billing, aggressively jostling for space and power in international affairs. Other leaders in these countries, who had leanings towards socialism or towards free-market economics, now have relatively low standing and are seen as indecisive relics from a bygone age.

So, what are the consequences of these three shifts?

The need for political re-invention: The discrediting of both socialism and of free-market economics has shrunk the political space in which most pro-poor Indian political parties, such as the Congress, have sought to operate. These parties, therefore, will have to reinvent themselves. How they do so will have a significant bearing on Indian politics and policy over the next decade.

On a more global basis, the concerted rise of hypernationalism in a range of relatively sophisticated emerging economies (for example, Russia, Turkey, India) is not accidental. As these countries urbanise, there is an increasing need for people who have left their rural roots behind to find a new source of identity. And as the middle class in these countries becomes increasingly prosperous, it gets confident enough to seek identities which are less Western and more indigenous.

Leaders like Erdogan and Modi, by driving home a philosophy of nationalist pride mingled with religious sentiment, have successfully captured the support of both the urban underclass and the urban middle class. Their political rivals—who have hitherto banked either on socialist economics or on narrow identity politics—will have to reinvent themselves.

Unstable geopolitics: As international politics shifts from an era of American domination to one where other powers such as China, Russia and India also seek to assert their influence, geopolitics looks likely to become more unstable. To that extent, the recent Russian foray into Ukraine could well be the first of such crises.

Unpredictable economics: The new strongmen politicians don’t have any fixed economic ideology. They are willing to do whatever it takes to lift growth and subdue inflation, and in the first 4-5 years of their tenure, they seem to be able to pull it off.

However, as their rule endures, the economic impact becomes more mixed and the lack of structural change in these economies is more obvious. In this regard, this brand of “strongman economics” is not only less predictable than what the East Asian nations practised or what Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan practised, its longer-term economic credentials are also more suspect.

Familiar investment constructs So, how should one invest in our brave new world where familiar political constructs—at home and abroad—are breaking down and where economic ideologies are no longer the path markers that they used to be?

Alphonse Karr, the editor of the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro, famously said that “the more things change, the more they remain the same”. That adage works well in the field of investment.

My study of the best-performing Indian portfolios over the past 15 years suggests that a sensible way to invest in stocks for the long run hinges around investing in companies (a) whose business models are easy to understand; (b) which generate healthy levels of return on capital employed (RoCE); and (c) which have a healthy revenue growth.

Indian companies which generate healthy RoCE and healthy revenue growth over long periods of time are very hard to find. But the good news is that when you pack your portfolio with such companies, you usually get market-beating returns.

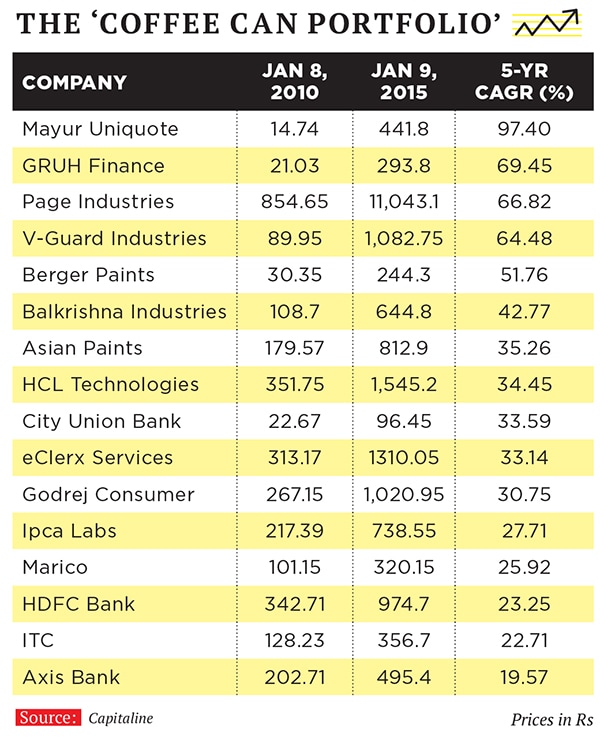

So, for example, if on June 30, 2000, you had invested in seven companies which had in the preceding 10 years generated RoCEs greater than 15 percent—and revenue growth above 10 percent—every year then, over the next 10 years (2000 to 2010), your portfolio would have compounded annually at 16.7 percent versus the 14.1 percent that the Sensex delivered over the same period. Had you repeated the same exercise a year later, you would have had six stocks in your portfolio. And in the 10 years from June 30, 2001, your portfolio would have generated 21.7 percent per annum versus the Sensex’s 18.5 percent. In fact, my colleagues at Ambit find that this approach—dubbed the ‘Coffee Can Portfolio’—has outperformed the Sensex fairly metronomically over the past 15 years.

For the patient investor who wants to earn healthy returns from equities in an uncertain world, I believe the Coffee Can Portfolio is close to being an ideal construct. Using the last 10 years’ financial data, my colleagues have created a Coffee Can Portfolio for the next 10 years containing 16 stocks (see table).

With that, I wish you the best of luck in life and in business in 2015.

(Ambit and its associates have managed the QIP issue of City Union Bank and have received compensation from them. Ambit and its associates have financial interests in Asian Paints, Axis Bank, City Union Bank, HCL Tech, ITCL and HDFC Bank as on December 26, 2014. I have no personal holdings in any of the stocks mentioned in the article.)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)