Investing in 2017: The return of the large-caps

Inflated valuations have made mid-caps prohibitive. And that segment's loss is the large-caps' gain

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

Mid-cap stocks have been the flavour of the last five years. The NSE’s Nifty Full Midcap 100 index went up by 17 percent annually over the last five years against 10.56 percent for the Nifty 50 in the same period; many top mid-cap funds gave returns of as much as 30 percent annually. But are these returns from mid-caps sustainable?

“Three years ago, the mid-cap segment was completely undervalued and there was an 80 percent chance of you picking up a winner. Now that chance has gone down to 20 percent,” says Neelesh Surana, chief investment officer (CIO) of the mutual fund Mirae Asset. “It is now going to be difficult to find undervalued mid-cap companies but that is not to say they are impossible to find.”

In comparison, then, are large-caps—the top 200 companies by market capitalisation—beginning to look attractive? Certainly, from a risk-return perspective, say fund managers.

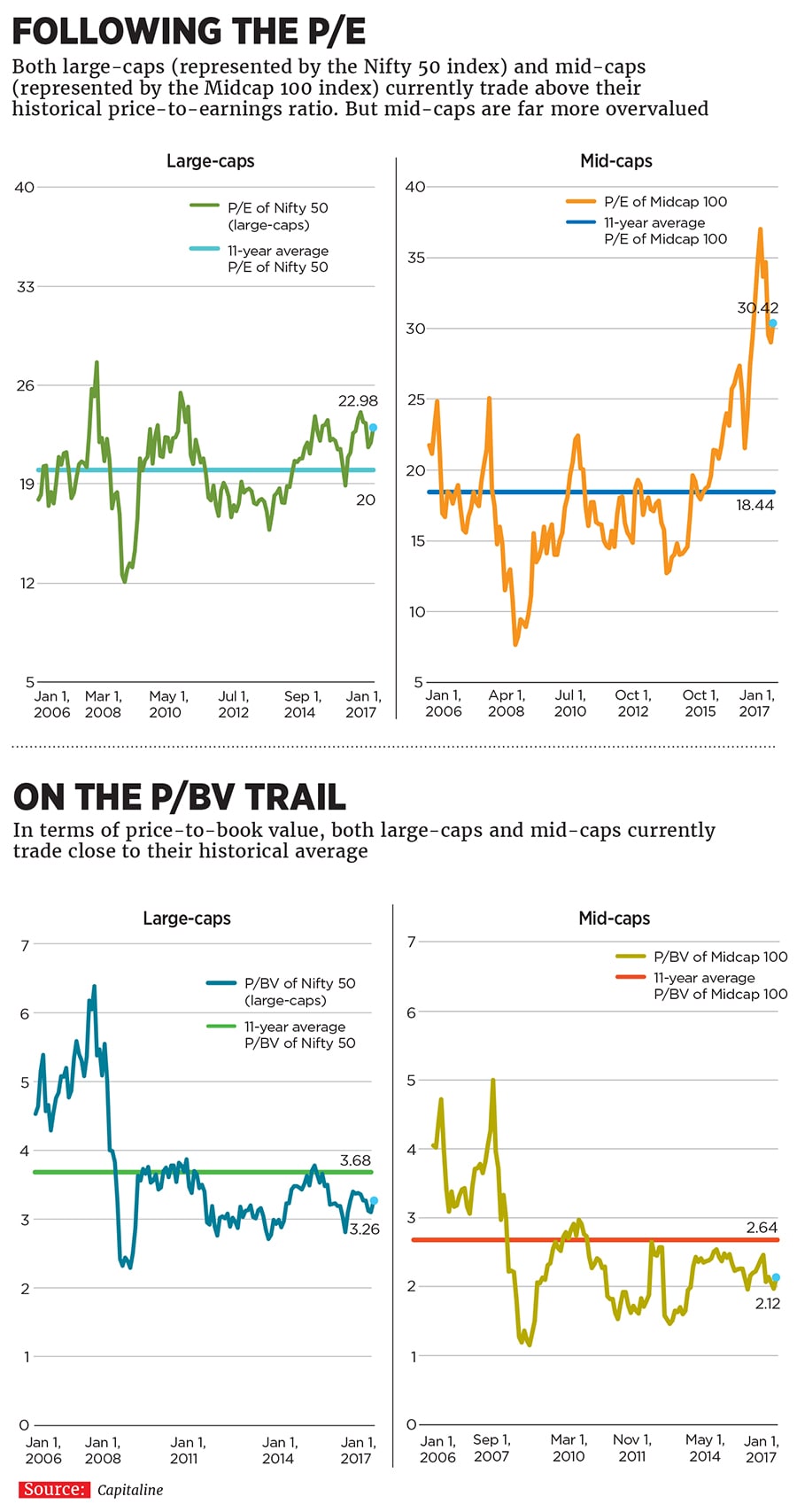

Large-cap stocks are currently valued at a price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple of 23 times—this is close to their 11-year average of 20. Mid-cap stocks, on the other hand, have a P/E multiple of 30 which appears expensive compared to their 11-year average of 18 (see chart Following the P/E). It then becomes prudent for investors to limit their exposure to mid-caps.

As any fund manager worth her stock will tell you, most mid-caps reach a point from where it becomes difficult to grow. That is typically the time for exits. Then there are mid-caps that operate in the real estate and infrastructure space which end up taking too much debt and are not able to perform after they hit a critical size. One such example is Unitech, a real estate infrastructure company, which was a favourite mid-cap stock in 2007. After the global financial crisis, however, it has lost 90 percent of its value.

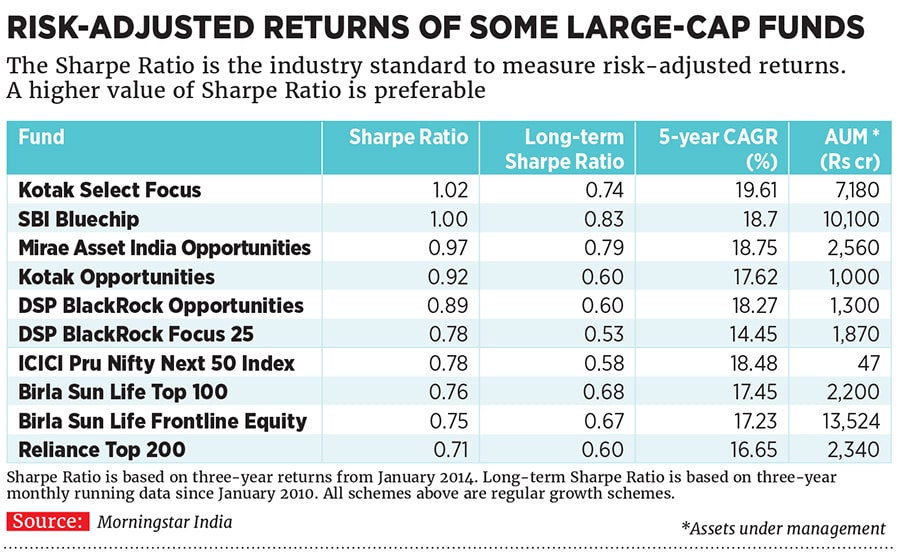

Rajeev Thakkar, CIO, PPFAS Mutual Fund, says that by the nature of the size and the market that large-cap companies cater to, they are less risky and have a well-diversified product portfolio. “Large-cap companies are less risky because they have more product segments. They are also good at managing their debts and have a professional management,” says Thakkar.

Valuations of large-caps have gone up but mid-caps are far more expensive

The relative safety of large-cap stocks is also higher because large-cap companies have more exposure to global growth. And, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), global economic activity is expected to pick up in 2017-2018: Growth in both advanced economies and emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) is forecast to accelerate in the next fiscal, up to 3.4 percent and 3.6 percent respectively.The IMF’s optimism about global growth directly impacts the fortunes of large-cap companies, agrees Manish Gunwani, deputy CIO, ICICI Prudential AMC. “If global growth is expected to be robust, driven by developing countries, then large-cap companies have more to gain than the mid-cap segment because the former deal in information technology, oil and gas, metals and pharma.” These sectors have strong linkages in foreign markets, particularly in terms of pricing.

The Mid-Cap Worry

A scan of the quarterly data for both the Nifty 50 as well as the Midcap 100 companies reveals that the December 2016 quarter was one of the worst for both segments of the market, but the Nifty 50 has shown a better performance.

Just on the basis of this data, it is clear that mid-cap valuations are inflated. Yet, the inflows keep coming in through domestic mutual funds.

This is a far cry from nearly a decade ago, when mid-cap stocks lost favour after the 2008 financial crisis. In fact, data from investment research firm Morningstar India show that inflows for mid-cap funds as well as large-cap funds remained negative till December 2013: That month saw a reversal and mid-cap funds had a positive inflow of Rs 38 crore. They continued to grow in popularity, and by May 2014, net inflows had touched Rs 1,194 crore. Positive investor sentiment also manifested in positive inflows into large-cap funds, which in subsequent years exceeded inflows into mid-cap funds.

This is a far cry from nearly a decade ago, when mid-cap stocks lost favour after the 2008 financial crisis. In fact, data from investment research firm Morningstar India show that inflows for mid-cap funds as well as large-cap funds remained negative till December 2013: That month saw a reversal and mid-cap funds had a positive inflow of Rs 38 crore. They continued to grow in popularity, and by May 2014, net inflows had touched Rs 1,194 crore. Positive investor sentiment also manifested in positive inflows into large-cap funds, which in subsequent years exceeded inflows into mid-cap funds.

Late last year, two events seriously affected investor sentiment. On November 8, the Indian government demonetised high-value currency notes and on the same day Donald Trump was elected president of the United States.

Though demonetisation was expected to affect the sales of listed companies, data for auto, banks, cement and consumer goods has remained positive for the October-December quarter.

“In terms of demonetisation, the hit has been more for the unorganised sector than the organised sector. So the listed space is not affected,” says Gunwani. “The market has already discounted the Trump protectionism for pharma and IT stocks.”

In the past few months, however, while the valuations of large-caps have also gone up, mid-caps look far more expensive.

Unlike in the large-caps space, fund managers argue, investment calls in the mid- and micro-caps space are usually management-specific. And the right calls can yield the right results. Take the example of DSP BlackRock Micro Cap fund which, even on a one-year basis, has given a 40 percent return.

In fact, fund managers we spoke to say that the likelihood of a mid-cap crash is low. They believe growth will return because the effect of demonetisation has already played out. And even if growth is not as per expectation of, say, 12 to 15 percent in terms of profits, the stocks will, at worst, stagnate and not experience a huge correction. This is because the flows from domestic funds, as mentioned earlier, are sticky.

“Risk becomes an issue only when there is no growth. I think growth [in mid-caps] will come back but you will have to choose sectors or stocks carefully. But I agree that the valuations of mid-caps are much higher compared to large-caps,” says Mahesh Patil, co-CIO of Birla Sun Life Mutual Fund, who manages the Birla Frontline Equity Fund.

Patil points to the huge potential in the large-cap space, particularly in the banking and financial sector, as well as the auto sector. He also finds the oil and gas sector attractive because it is trading at low P/E multiples of 10. At the same time, he cautions that the IT and FMCG sectors will experience moderate growth and are highly valued at current prices; FMCG large-caps are trading at a P/E of 45 times.

Anup Maheshwari, head of equities at DSP BlackRock, too, agrees that mid-caps are now expensive.

“The large-cap space looks relatively more attractive. Equities in general are now richly valued. Investors should now not think of quick returns when investing in this asset class,” he says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)