Chandra Shekhar Ghosh's Bandhan banks on building ties with the underprivileged

He has no degree in finance or management. But that will not stop Chandra Shekhar Ghosh from transforming his successful microfinance company, Bandhan Financial Services, into a full-fledged bank

Award: Entrepreneur with social Impact

Chandra Shekhar Ghosh

Chairman and Managing Director, Bandhan Financial Services Pvt Ltd

Age: 54

Interests outside work: Reading, music and photography

Why he won this award: Creating a source of living for India’s underprivileged and now looking to include over 58 lakh unbanked customers under the banking purview. And this is just the beginning

It took two defining moments for Chandra Shekhar Ghosh to get to where he is today. The first was an encounter with a woman and her three-year-old daughter in the interiors of West Bengal. This was in the 1990s, when Ghosh was a health officer with a local NGO. After observing the mother boiling a pot of rice outside her hut, while her daughter was busy making a meal of the dust and dirt around her, Ghosh stepped in and delivered a sermon on the importance of healthy habits. “I’ll never forget the mother’s reply,” he says. “She told me, ‘My daughter has been asking for fish for three days now. And today, I will make another false promise to her, knowing I cannot give her what she wants. That’s what saddens me more than anything else’.”

What moved Ghosh more than just the deprivation was her resignation to the situation.

The second instance also took place in West Bengal when a conversation with a vegetable vendor in one of Kolkata’s busy markets brought home the tyranny of moneylending. The vendor was paying a moneylender an annual interest of about 700 percent on a daily loan of Rs 500. Every morning, he would borrow some money from the lender and return the principal amount with interest in the evening. “The vendor felt this was a good deal,” says the 54-year-old Ghosh. “He told me that his daily interest was the equivalent of just two cups of tea, and argued that even if he managed the impossible and got a loan from a bank without a guarantor, he would be paying more than his current interest just on transport—getting to and from the bank. The lender, on the other hand, would come to his house every evening to collect the dues.”

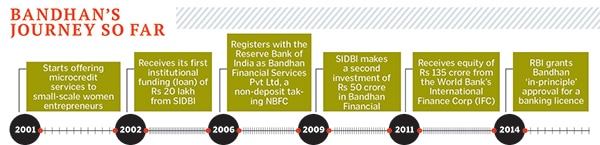

These were the conversations playing in his head when Ghosh decided to start a microfinance organisation with the goal of lending money to women entrepreneurs who were marginalised by society but were willing to try their hand at a small-scale business. Bandhan was born in 2001. Five years later, he registered his organisation as a non-deposit taking, non-banking financial company (NBFC) with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), and Bandhan became Bandhan Financial Services Pvt Ltd. It now provides loans to people in rural and semi-urban India irrespective of gender, though women empowerment remains its primary goal.

Even at the inception stage, Ghosh knew that he wanted a long-term solution to poverty alleviation. “I was never keen on an NGO model or charity because they are mostly for the short term,” he says. “We wanted to impact the lives of a large number of people who are not able to have food even twice a day. How can we contribute towards their well-being? First, there has to be a stable flow of income; only then can other areas like health and education be taken care of.”

For 14 years, Bandhan Financial has remained true to its founder’s philosophy. But now, the ever-evolving NBFC is preparing itself for its next big leap: It’s on the cusp of becoming a full-fledged bank. If all goes as per plan, the proposed Bandhan Bank will be operational by the first quarter of the next financial year with an initial 600 branches across India.

In April this year, the RBI awarded Bandhan Financial a preliminary licence to set up new banks in India. It’s the first microfinance organisation in the country to win a coveted bank licence, staving off competition from 23 companies, including corporate giants such as Aditya Birla Group, Larsen & Toubro and Anil Ambani’s Reliance Capital. The RBI last issued a bank licence a decade ago to Yes Bank. (The only other firm to receive an RBI licence this year was infrastructure financing company IDFC.)

The excitement among employees is palpable. And among industry analysts, there’s plenty of speculation over the route Ghosh will choose. Can a bank have the leanings of an NGO and still survive? Or will he target the middle class, which is being served by commercial banks? Will he rewrite the rules so as not to dilute Bandhan’s original goal of poverty alleviation and women’s empowerment?

Ghosh is clear. “It is going to focus on the unbanked population. We will have an urban presence, but our focus will be the interiors of India. Ours is a dual aim—financial inclusion as well as social inclusion of the community.”

At present, India has 89 scheduled commercial banks (excluding Bandhan and IDFC), 64 regional rural banks, 1,606 urban cooperative banks, and 93,551 rural cooperative banks. But half of the country’s 1.2 billion people are still outside the banking purview. Ghosh wants to change that, one family at a time. And he has a plan.

If he can’t get a customer to the bank, the bank will go to the customer. Bandhan’s personnel will do the rounds of villages and meet farmers while they work in their fields. They will be armed with hand-held biometric devices that will allow villagers to make entries of their deposits without physically going to the bank.

Ghosh and his team are identifying branch locations; the existing 2,016 offices will operate as sub-branches.

He has also assembled a 30-member team that is working exclusively on the transition, overseeing key departments, including risk management, IT, operations, internal audit, human resources and business development. Consulting firm Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu India has been roped in to help with the transformation.

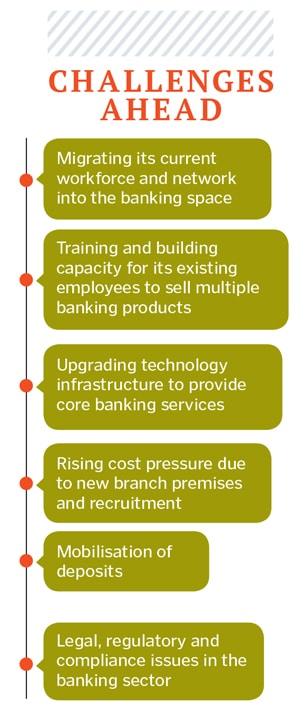

The training programme has gained popularity among the staff. About 52 percent of Bandhan’s employees are undergraduates and many hail from small towns. Up until now, they were dealing only with the credit products in rural and semi-urban areas, but Ghosh wants to expand their scope and train them to sell multiple banking products and services across Bandhan Bank’s branches. “More than anything, I want to prove to the world that my existing staff is capable of serving bank customers,” says Ghosh.

His enthusiasm has permeated down the ranks; employees have started attending training programmes which are held at eight training centres across India. “Our CMD [Ghosh] believes that once a person knows how to drive a car, the model doesn’t matter. Someone who can drive a Maruti can also learn to drive a Mercedes-Benz,” says senior training manager Saikat Banerjee.

The transition will not be easy. “A bank is fundamentally a different animal. The primary concern will be to migrate our current workforce into a much larger banking space. The challenge is to get the existing team into the banking mindset,” says Asish Sengupta, head of human resources at Bandhan Financial. Sengupta, who joined Bandhan in February, is a retired banker and has been in the industry for 37 years.

Experts, however, point out that it’s not just the manpower, training or cultural concerns that Bandhan has to focus on. There are complex legal, regulatory and compliance issues that banks have to adhere to.

Samit Ghosh, founder and CEO, Ujjivan Financial Services, a Bangalore-based microfinance institution, feels Bandhan’s banking model has to be very different to make it a viable proposition. “The cost base has to be lower because the transaction size, savings account and balances are much smaller. It should not target the middle class as they are already served by the commercial banks,” he says.

But Ghosh’s colleagues are confident that his hands-on approach will show them the way forward. Ashoka Chatterjee, institutional finance head of Bandhan Financial, says the new bank will not be a clone of its peers. “The ticket size of the transactions might be lower, but the customer base at over 58 lakh is huge. At present, 78 percent of Bandhan’s reach is in rural and semi-urban India. It will be a microfinance-focussed bank,” she says.

With total FY14 income of Rs 1,213 crore and total loans outstanding (as of August 31, 2014) of Rs 6,446 crore, Bandhan Financial is already a David among Goliaths. It wouldn’t be wrong to say the same of its founder. Unlike the majority of his peers who have management degrees and have worked in the banking sector before moving to microfinance companies, Ghosh is not a banker. “But I have a strong connect at the grassroots level. The last 13 years have been a learning experience and helped me understand the needs of those who are financially and socially excluded,” he says.

Bandhan has come a long way since Ghosh started it with Rs 2 lakh—from his personal savings—in Bagnan, a town in the Howrah district of West Bengal. It is one of India’s most profitable NBFCs. This, despite having some of the lowest interest rates in the sector: Bandhan Financial charges 22.4 percent per annum (reducing rate) for business loans and 12 percent per annum (reducing rate) for non-business loans such as health and education loans. (The margin cap or interest cap that can be charged by any NBFC as per RBI guidelines is 26 percent.)

Over the years, Ghosh and Bandhan have received numerous awards; he joined the ranks of the prestigious Ashoka India Fellows in 2007. In the same year, Bandhan Financial was ranked second by Forbes in its first ever list of the top 50 microfinance institutions in the world.

But he’s not too comfortable with the accolades. It’s probably because he never imagined himself as an entrepreneur. Ghosh, who was born in Agartala, Tripura, in 1960, hails from a family of refugees. His parents were driven out of Dhaka, Bangladesh, during Partition. His father, the late Haripada Ghosh, ran a sweet shop which was the family’s only source of income. But despite limited financial resources, Haripada sent him to the University of Dhaka from where he graduated in 1984, with an MSc in statistics.

Ghosh then joined BRAC— a non-governmental development organisation in Bangladesh—as a field officer. He spent five years in some of the poorest parts of the country before returning to India in 1990, where he continued working with NGOs operating out of West Bengal. By the turn of the century, Ghosh wanted to create a more sustainable model, one that would empower the poor. And, in 2000, he quit the Village Welfare Society, a Kolkata-based NGO, to start Bandhan.

In 2002, a year later, he got his first institutional investment of Rs 20 lakh from the Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI), which he utilised to scale up operations. Today, some of the major institutional investors in Bandhan Financial include the World Bank’s private investment arm, International Finance Corporation, which invested Rs 135 crore in the company in 2011 and holds a 10.93 percent stake while SIDBI has a 9.63 percent stake. (It had made a second investment of Rs 50 crore in Bandhan Financial in 2009.)

Ghosh, who resides in Kolkata, says the number of borrowers has risen at a compound annual growth rate of 30 percent over the last five years while loans outstanding grew at 54 percent. The microfinance institution has a repayment rate of 99.92 percent with current net non-performing assets (NPA) at only 0.10 percent. He wants the same success for Bandhan Bank.

More importantly, Bandhan was built on the ties that bound its founder to rural India. And he wants the bank to strengthen this commitment.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)