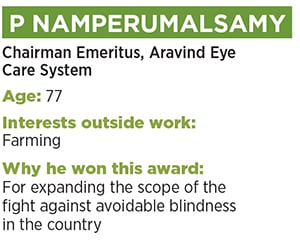

P Namperumalsamy: The visionary who steers Aravind Eye Care

By expanding Aravind Eye Care's focus, P Namperumalsamy is taking the fight against avoidable blindness to the next level

It is 7 am on a September morning and the operation theatres at Aravind Eye Care System’s hospital in Madurai are a beehive of activity. There is a striking resemblance to an assembly line more often seen in a manufacturing facility. Each operation theatre has four tables where two doctors operate independently. Each doctor has a large microscope stationed between two tables. When a doctor walks into the theatre, a cataract patient, fully prepped by two mid-level ophthalmic personnel (MLOPs), is wheeled in for surgery. The doctor quickly looks through the patient’s case sheet and gets to work—he removes the affected lens in the eye and replaces it with artificial lens. Even as he is doing this, a second patient is wheeled in, positioned on the other table and prepped by the MLOPs (each doctor has two MLOPs to assist him). After inserting the lens, the doctor simply swings his microscope across and shifts his attention to the second patient, while the MLOPs take over the necessary post-operative procedures—like bandaging the eye—and wheel the first patient out. As he is completing the surgery on the second patient, a third patient, prepped and ready, awaits his turn at the first table. The process is repeated till about 3 pm every day.

By getting a doctor to focus on just the critical part of the surgery (removing and replacing the lens in the eye), building an army of qualified MLOPs who handle other aspects of the operation, and putting in place an assembly-line process, Aravind Eye Care has ensured that a doctor’s throughput is high. An Aravind Eye Care doctor takes just 5 to 10 minutes per patient. This enables him to perform, on an average, 50 surgeries per day and at least 2,000 a year (doctors elsewhere manage, at best, 300-400 surgeries a year and in developed nations the figure, at 200, is even lower). It is this scale that has enabled it to execute its vision of fighting avoidable blindness and restoring eyesight to thousands of people whether they are able to afford it or not.

“Last year, 22 percent of the 4.08 lakh surgeries we did were for free, 28 percent were heavily subsidised and only the balance 50 percent were charged fully,” says P Namperumalsamy, chairman emeritus, Aravind Eye Care, and one of the founding members of the organisation.

Thanks to a model that leverages scale, the organisation—its innovative model has been taught as a case study at Harvard Business School since 1993—is able to service its social commitment without compromising on its profitability: In 2014-15, Aravind Eye Care’s income was Rs 233.74 crore while its expenses were only Rs 162.98 crore, generating a surplus of Rs 70.76 crore.

Aravind Eye Care has also expanded its reach remarkably, conducting over 2,500 eye camps across Tamil Nadu and Puducherry to identify people who need treatment. It keeps costs low by manufacturing—and also exporting to 146 countries—lenses, sutures and other consumables required during and after surgery. It seeks innovative but effective solutions to bottlenecks. For instance, the shortage of doctors is being tackled by developing qualified MLOPs—Aravind Eye Care has 2,800 of them now—who take on the non-critical functions, freeing up a doctor’s time. Finally, it prices its services in a sustainable manner (it offers eight price points to paying and subsidised patients). This ensures that Aravind Eye Care makes enough money and remains a zero-debt organisation that does not seek donations.

“Aravind Eye Care operates with a social heart and a business brain,” says Vijay Govindarajan, Coxe Distinguished Professor at Tuck School of Business, Dartmouth, and Marvin Bower Fellow at Harvard Business School. “They have the heart of a non-profit and the brain of a for-profit, apply modern management methods to dramatically lower costs while delivering world-class healthcare.”

Namperumalsamy, 77, is soft-spoken and measures his words carefully as he speaks to Forbes India seated in his spartan office in Madurai. “Aravind Eye Care was the dream of my late brother-in-law Dr J Venkataswamy (affectionately called Dr V) who started the organisation in 1976 to eliminate needless blindness in this part of the country,” he says. “But for him, we would not have achieved all this.” Dr V’s role and passion has been well-documented and he is today revered within the organisation and respected outside.

Namperumalsamy’s (or Dr Nam, as he is often referred to) contribution is significant as well. In 1977, he quit a comfortable government job—he was assistant professor of ophthalmology at Madurai Medical College—and joined his brother-in-law full-time, a move that emboldened Dr V to expand what started in 1976 as an 11-bed hospital in Madurai. Today, Aravind Eye Care has 11 hospitals across Tamil Nadu and Puducherry as well as 59 primary eye care centres and six community centres. Soon, it will start a hospital in Chennai and foray into Andhra Pradesh with a centre in Tirupati.

In 40 years since its inception, the organisation has handled over 45 million outpatients and performed 5.6 million sight-restoring surgeries (almost 60 percent of them either free or highly subsidised). What’s more, this scale has been achieved without compromising on quality. At Aravind Eye Care, the infection rate, a measure of quality in eye care surgeries, is among the lowest in the world. “We were able to achieve this success for two reasons. One, through the systems we put in place, and two, the values and mindset that were internalised,” says RD Thulasiraj, director, operations, Aravind Eye Care. “Dr V spread the values on a personal level while Dr Nam institutionalised them.”

Dr Nam has also been responsible for broadening the scope and expertise of the organisation in several ways. “He played a role in changing Aravind Eye Care’s perception of being a cataract factory,” says Thulasiraj. He looked beyond cataract and also focussed on diabetic retinopathy and vitreous surgery; he was the first eye surgeon in India to master this technique used for correcting retinal detachment way back in 1974. Today, only 61 percent of the surgeries done at Aravind Eye Care are for cataract.

Dr Nam has also been responsible for broadening the scope and expertise of the organisation in several ways. “He played a role in changing Aravind Eye Care’s perception of being a cataract factory,” says Thulasiraj. He looked beyond cataract and also focussed on diabetic retinopathy and vitreous surgery; he was the first eye surgeon in India to master this technique used for correcting retinal detachment way back in 1974. Today, only 61 percent of the surgeries done at Aravind Eye Care are for cataract. Ask him about diabetic retinopathy and Dr Nam becomes more expressive. Clearly, it is a subject close to his heart. “As many as 65 million people suffer from diabetes in India and the eyesight of 27 percent of them will be affected,” he says. “The tragedy is diabetic retinopathy is a symptomless condition and the affected persons lose their eyesight suddenly. Once that happens, it is irreversible.” Periodic examination is the only solution and Aravind Eye Care has been creating awareness by conducting special camps, working with the government (public health centres) and diabetologists.

For the doctor, though, it doesn’t end there. “Dr Nam is working with various companies to develop a low-cost camera that can be used to expand the reach of screening. The camera he is designing is such that any doctor can take a picture and email it to an expert who can check whether the eye has been affected on account of diabetes,” says RD Ravindran, chairman, Aravind Eye Care. “He sees the fight against diabetic retinopathy as a crusade.”

Dr Nam has also been responsible for the setting up of vision centres for primary eye care. “We realised that the screening camps we conduct in rural areas were not reaching everyone,” says Ravindran. “To overcome this challenge, Dr Nam began setting up vision centres, which are manned by 2 MLOPs who do the basic tests and send the data digitally to the main hospital for further evaluation.” Today, Aravind Eye Care has 57 such centres, ensuring better coverage.

“We [had earlier] conducted eye camps at our convenience, and not the patient’s. A permanent facility, which would cost just around Rs 5 lakh, goes a long way in improving the quality of eye care,” explains Dr Nam.

Born into a farming family in a small village near Theni town, a three-hour drive from Madurai in southern Tamil Nadu, Dr Nam’s aspirations to become a doctor actually came from his father. His mother was illiterate, his father had managed to study only up to elementary school. But the two were determined to educate the children (Dr Nam and his four sisters). It was not an easy task, neither for the children nor for the family. While his father had to borrow money to educate the children, Dr Nam walked over a mile each way to get to the government school. This went up to three miles each way by the time he got to the higher classes (9 to 11). But he was proficient at studies and though he initially wanted to become an engineer, he acceded to his father’s request and took up medicine. In 1965, when he was a house surgeon at Madurai Medical College, he married his classmate Dr G Natchiar (an arranged marriage). Dr V, who was Natchiar’s elder brother, was also his professor; he persuaded his sister and her husband to pursue ophthalmology as their post-graduate specialisation.

Dr Nam then took up fellowships in diabetic retinopathy and vitreous surgery in the US while working as an assistant professor of ophthalmology at Madurai Medical College. But when he sought to take up another fellowship at Harvard University in 1977, his employer—the Madurai college—denied permission. “They refused and I decided to give up the job,” he says. After returning from the fellowship, he joined Aravind Eye Care.

Since then, the centre has achieved various milestones, and Dr Nam has been recognised many times for his work. In 2006, he was awarded the BC Roy Award by the Medical Council of India in the ‘Eminent Medical Teacher’ category, and in 2007 he was awarded the Padma Shri. In 2010, Time magazine named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world.

Besides diabetic retinopathy, Dr Nam is currently focussed on two other important areas—research and a ‘Vision for All’ initiative that he started recently in Theni district. “Dr Nam gave us the focus on research,” says his wife, Dr Natchiar, vice-chairman emeritus at Aravind Eye Care. “We have the most well-equipped and well-staffed research facility in the country where 20 PhDs are trained at any given time.” Dr Nam’s focus is basic research that will prevent blindness. “Work is on to tackle corneal ulcer and find biomarkers to treat diabetic retinopathy, to name a few projects,” he says.

With the ‘Vision for All’ initiative, he is aiming to set more benchmarks. “I want to make Theni district the best eye care zone in the country where nobody needs to travel more than nine kilometres for treatment/check-up,” he says. “I want to show that this is possible and can become a benchmark across the country.”

In the process, he has managed to emerge from the shadows of his illustrious mentor Dr V, who worked to eradicate avoidable blindness. Dr Nam has gone a step further, helping fight blindness that is incurable but preventable.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X