Paytm: The wonder wallet

Paytm started as a mobile wallet to simplify payments. Today it is aiding financial inclusion

Image: Amit Verma

Somewhere in Noida’s Sector 5, in a nondescript building on a noisy, dusty, mosquito-infested road that’s too narrow to be called a highway but too wide to qualify as a street, where rickshaws and pedestrians compete with speeding SUVs, a revolution is churning. And it’s spreading.

Outside the building, it took a while for Aas, in his Hyundai Eon UberGo, to find me. I didn’t get around to asking him his last name. He was a tad dismayed that my default payment option was Paytm. “Cash karte to haat mein kuch mil jaata… aaj jeb to pura khali hain, sabhi customer ne Paytm kar diya aaj,” he said, lamenting the fact that I, like all his customers for that day, had selected the Paytm option, leaving him without any cash. Uber’s tie up with Paytm in November 2014 helps passengers walk away at the end of a ride, with the fare being deducted automatically from their Paytm account.

Contributing to Aas’s dismay was the Rs 100-per-cab toll he sometimes has to dish out while heading into Delhi from Noida. If the personnel at the toll booth didn’t find his monthly pass valid, he could either argue, or pay up and move on. Because he made this trip at least a few times every day, Aas could do without the hassle.

However, it’s only a matter of time before—like the toll booth at the Bandra-Worli Sea Link in Mumbai, where payment via Paytm wallet is an option—he too can choose to have a Paytm account from which the correct toll amount will get docked automatically. He won’t need to dish out cash, or even slow down as radio chip-based cashless payments, such as Paytm’s FASTag, gain popularity.

Aas will also be able to pay his children’s school fees, or squirrel away a portion of the day’s earnings into a savings account from within his Paytm app. He may even be eligible for cashless health insurance that Paytm has rolled out for autorickshaw and cab drivers, in partnership with insurer Tata AIG.

Soon, Aas will have enough of a “digital exhaust”—as Nandan Nilekani, former chairman of the Unique Identification Authority of India likes to call digital footprint—for Paytm to give him convenient loans. So, goodbye loan sharks.

Such are the ideas being thrown around in that nondescript Noida building that only has a large-ish signboard outside to give away its status as the heart of India’s most famous fintech startup. “It’s very humbling. What we thought was that we’re solving payments, but what we learnt was we’re bringing millions of people into the mainstream economy that they never really benefited from earlier,” says Vijay Shekhar Sharma (38), founder of Paytm. “This started in the world of Aadhaar and is moving into the world of financial services with things like Paytm. We will bring half a billion Indians into the mainstream economy.”

Widespread adoption of digital finance, or smartphone-based payments and financial services, could increase the GDPs of all emerging economies by 6 percent, or a total of $3.7 trillion, by 2025, says consulting major McKinsey & Co in a September 2016 report. This is the equivalent of adding an economy the size of Germany to the world, and could create up to 95 million new jobs across all sectors, the report points out. Lower-income India could add as much as 10 to 12 percent.

By then, he had transformed from a shy 15-year-old from Aligarh in Uttar Pradesh, who could barely speak English—he had studied in a Hindi medium school, kept topping his class, and ended up in Class 10 when he was just 12—to a “starter”, as he calls himself sometimes, with dreams of building something in India. His inspiration came from the stories he read about Silicon Valley in used copies of business magazines.

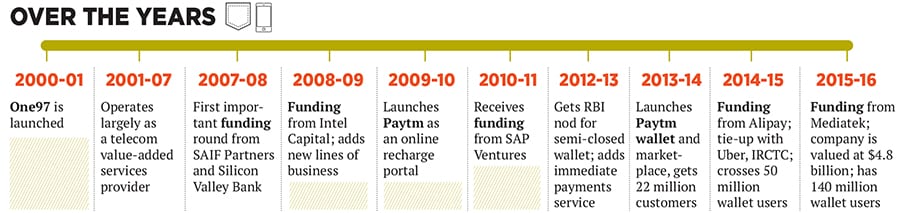

One97, for a long time, was a mobile marketing business with telecom customers. Today it operates the Paytm mobile wallet or, rather, the Paytm platform (perhaps it’s no longer sufficient to call it a wallet). The wallet was launched in 2014, along with an online shopping marketplace that competes with Flipkart and Snapdeal.

And “Paytm kar do” must become the easiest option to get through a typical day for any urban Indian, from the moment they wake up to the time they hit the sack, says Renu Satti, 35, vice president of One97, and one of Sharma’s long-time colleagues. She started out as head of HR a decade ago but now runs a big chunk of the core payments business.

Satti—a powerful combination of childlike enthusiasm and shrewd business acumen—carries an infographic in her head, which she can sketch out at the drop of a hat, marking out every possible scenario from dawn to dusk where one might use Paytm. “Today you can pay school fees with Paytm,” she says. (Several schools in Delhi and NCR have started to accept payments through Paytm.)

At the office’s partially open terrace that functions as a common dining floor, the caterer has pasted stickers of QR codes on a couple of rickety wooden tables. Anyone who comes to the canteen can scan the code via their Paytm smartphone app and help themselves to lunch. Or snacks. Or tea. With no cash.

Sharma was delighted when I told him that I’d found my wallet to be empty and had paid Rs 35 for a vegetarian meal with my Paytm app. He dissolved into one of his unselfconscious, and hugely-infectious chuckles: A combination of crinkled eyes, a wide grin, gently shaking shoulders and a slight doubling-up with mirth.

He pulls out an iPhone to play a video he’s been sent. It shows how people are using the Alipay app to eat at a restaurant in China: The customers view the menu on their app, select their food, receive an expected time by when a waiter will serve them, and finally pay when they are done eating.

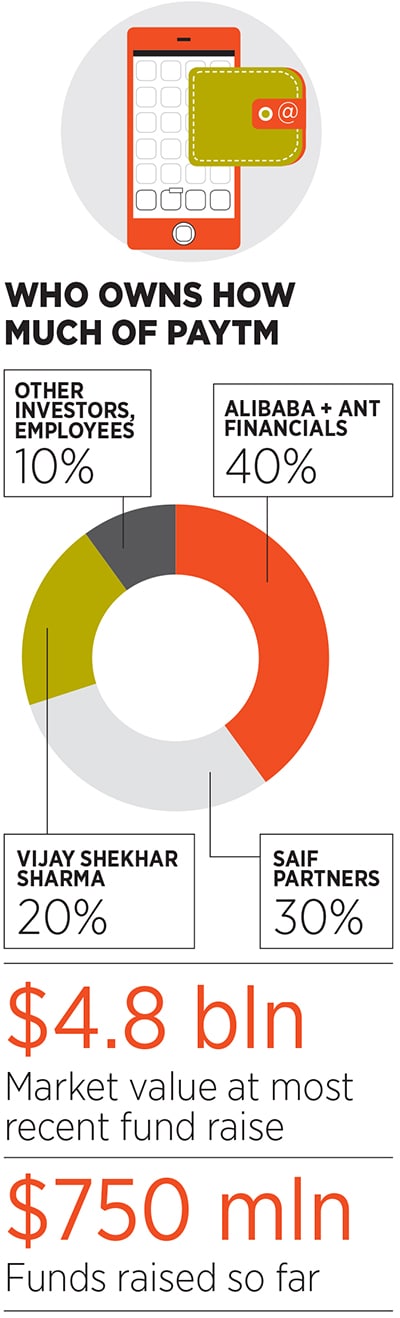

And that’s how far Paytm wants to go. It is now backed by China’s biggest ecommerce giant, the Alibaba Group, and is valued at $4.8 billion. The company has raised about $750 million so far, and is preparing for its next big launches by spinning off its marketplace business as a separate, independent, entity, and by opening a payments bank.

Offline to online

In the meantime, Sharma is growing what he calls “O2O (offline-to-online) commerce”, and could work the other way round as well, as Satti points out. It is essentially an extension of the online marketplace model, where the payment portion is brought online for local merchants who remain largely offline. For instance, a customer can scan a QR code to pay at a Mother Dairy outlet.

Sharma explains: “I discovered the offline-to-online model by accident in China, where it’s called ‘koube’. It is about things you buy on an app and consume in the physical world.” Conversations with people like Alibaba’s Founder and Chairman Jack Ma and his right-hand man, Vice Chairman Joseph Tsai, and investor SAIF Partners’ managing partner in India, Ravi Adusumalli, crystallised the plan.

While payments via QR codes, which Paytm launched in October 2015, bring offline merchants and schools into its fold, this year Sharma has rapidly added digital goods such as movie tickets, tickets for flights, trains and events, and gift cards. Paytm users can even book Renault’s small, hugely popular, runabout Kwid on the app and pick up the car from a showroom. “With 3 million transactions a day on Paytm, it’s a platform for showcasing a brand; we’re giving [businesses] that kind of reach,” Satti says.

While payments via QR codes, which Paytm launched in October 2015, bring offline merchants and schools into its fold, this year Sharma has rapidly added digital goods such as movie tickets, tickets for flights, trains and events, and gift cards. Paytm users can even book Renault’s small, hugely popular, runabout Kwid on the app and pick up the car from a showroom. “With 3 million transactions a day on Paytm, it’s a platform for showcasing a brand; we’re giving [businesses] that kind of reach,” Satti says.“There is an acceleration of the disruption taking place in the global financial services industry, with more capital than ever being invested around the world in startups and established ventures that are creating new financial products and solutions,” says Toby Heap, co-founder of Australia-based fintech investor H2 Ventures. ANT Financials, which together with Alibaba holds the largest stake in One97, has been ranked No. 1 in a list of 100 fintech innovators, in a survey recently concluded by H2 Ventures and accounting firm and consultancy KPMG.

The number of O2O transactions has moved from about 6,000 a day in January, when it started, to 3.16 lakh a day in September, Sharma says. “If we’re successful, we’ll have given the world a new business model.”

Satti can barely contain her excitement: “Six months ago, we didn’t have movie ticketing, or flight booking… we recently launched train bookings also. If one app can solve multiple problems, why would you have so many silo apps?” Her 5,000-strong staff is fanning out across cities, signing up anyone who can benefit from a commercial payment—from Mother Dairy to schools.

“Our goal is to have a super-app on which you can do everything, while the core will remain payments,” says Kiran Vasireddy, senior vice president, who heads Paytm’s payments business. “Eventually we would want people to pay for everything using the wallet and our larger mission is to make India a cashless country.”

“People should be able to walk out of their home without cash in their pockets,” Vasireddy says. “Our reach, with 6 lakh shops and merchants, is getting bigger than what the point-of-sale network is [network of card-swipe machines that merchants use for payment via debit and credit cards]. We intend to hit 10 lakh merchants this financial year.”

As a company that started out selling mobile marketing services to telecom customers, Paytm has come a long way. But it is also just getting started. “We hope to launch our payments bank over the next two months… everything will be mobile-centric. If you have to put money from your savings account into a money market fund or something, it will take a single click. If you have to pay for something, it will be a scan or a click,” Vasireddy says.

Paytm Ecommerce

As the payments business evolves into a full-blown financial services play, the thinking within Paytm is that its ecommerce marketplace needs freedom and flexibility to flourish.

“For us, ecommerce is actually an important part of the large financial services play. If a merchant is giving us data, then it’s an opportunity to build a differentiated business there,” Sharma points out. “The marketplace will get its own branding so that it is identified as an independent entity, and once it is a new company, we will have our own cycle of business and, in the long term, raise its own funding. We’re de-merging it, and creating a peer entity of Paytm.”

This way, argues Sharma, they are creating an entity that doesn’t have the obligation of remaining a part of Paytm; existing shareholders get their fair share of the new entity, while there opens up the opportunity of bringing in fresh investments and new shareholders as needed. “Today when we raise money, we have to park it in two silos, and as we add multiple businesses, we have to put it in more things. What if we wanted to raise money only for this vertical, which in itself is a large capital-hungry entity?” he says. The new entity is to be called Paytm Ecommerce Ltd, and its brand name will be disclosed “hopefully by year-end”.

In implementing its vision, Paytm faces the same barriers that other pioneering startups face in India. Inertia on the regulatory front is one, as is the “elusive mobile internet”, says Sharma. The most difficult one to tackle, however, could be how we work. We don’t have the work culture of the digital era yet in India, even though the young are quite savvy in using the smartphone, he says. “In Silicon Valley, when people say they will do something, they’ll live by it. In India, it’s common social behaviour to not do that.”

He adds: “We need to attract a lot of talent from outside, and there has been an initial rush of people back to India, but you’ve seen that it has not been all that successful.” Instead, Paytm has built its main R&D unit in Toronto, Canada. The current staff of 45 or so scientists, engineers, and programmers includes recruits from Google and BlackBerry, Vasireddy says.

They are doing everything from fault-proofing Paytm’s technologies, to behavioural analysis to artificial intelligence. Eventually, Sharma says, “we’ll have hundreds of people in Canada”. The company also has a development centre in Bengaluru, where it expects to expand operations as well. By 2020, Paytm aims to have 500 million customers and Rs 1 lakh crore of turnover—the net total of all payments made by those customers in a year. That compares with Rs 25,000 crore today, Sharma says.

His office is a desk alongside other young staff on one floor of the four-storeyed building in Noida. There’s no corner office to give him away and if you don’t know him by sight, the only way to locate him is to ask someone. Behind his desk, on the wall, flatscreen TVs show in real-time a seven-day rolling average of performance-by-transactions of each business unit within the company. Numbers flashing in green are growing versus the previous seven-day rolling average, and those flashing in red are declining. Also adorning the walls are posters of some of the world’s biggest entrepreneurs, including Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, “my favourite”, Sharma says.

As to actual revenues, Sharma didn’t allude to them, but Trak.in reported in August that One97 reported losses of Rs 1,534 crore for the fiscal year ended March 2016.

As Paytm seeks to achieve the 2020 target, the focus will be on growth and stability. “Today, success is about the number of users, but tomorrow it will be about our revenues and profits we generate, so we have to mature our processes to that level, and then think of an IPO,” says Sharma.

To judge whether a startup is successful, numbers tracked include success ratios, recharges, total transactions, unique users, new users, repeat users and gross merchandise volume. “We have massive repeat [users],” he says. The company had 140 million users as of September, and some 3 million checkouts happen every day. “We measure our growth week-on-week. Everybody here knows what transactions we have done, what the scorecard is.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X