Vinita & Nilesh Gupta: The Yin and Yang of Lupin

Putting their diverse management styles to work, Vinita and Nilesh Gupta are dreaming big billions for the pharma major

Image: Joshua Navalkar

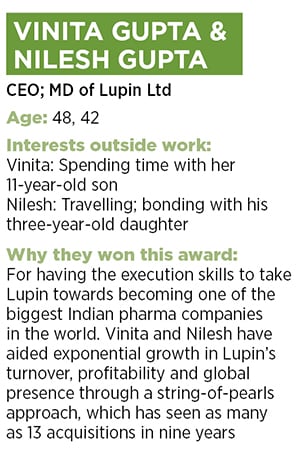

The duality and, yet, the underlying oneness signified by the oriental symbol of Yin and Yang is a near-perfect descriptor of the twin forces at work at Lupin: The outgoing Vinita Gupta and her back-end-focussed brother Nilesh Gupta.

The joint leaders of the seventh largest generic drug-maker in the world by sales, and the third largest pharma company in India, are a study in contrasts. Lupin’s chief executive officer, 48-year-old Vinita, is an extrovert, says Kamal K Sharma, Lupin’s vice chairman. Based in Baltimore, US, Vinita is a consummate networker who thrives on going out and meeting people. “I am constantly trying to meet leaders from other companies as well as other stakeholders to get a better sense of where the industry is going, what our peers are doing, looking at ways to adapt to the changing environment and collaborating with outside folks,” Vinita, an MBA from the Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, tells Forbes India during a phone interview.

Not surprising then that she has been entrusted with the task of building the pharmaceutical company’s front-end in the US, and playing a lead role in interactions with stakeholders, including customers and regulators. Her efforts have helped Lupin establish partnerships with marquee global names like Merck KGaA, the oldest pharma company in the world. Lupin has a strategic alliance with the Darmstadt, Germany-based Merck to jointly develop and market drugs. “Vinita is a very global-minded executive. She is extremely pragmatic and will surely take the company to newer heights,” says Belén Garijo, member of the executive board and CEO of Merck Healthcare.

Vinita, as Sharma puts it, “derives her energy from outside”.

Then there is Nilesh, 42, the company’s managing director (MD), who draws his energy from within. He isn’t much of a networker; at least, not externally. However, that isn’t to the detriment of his work. Within Lupin, he communicates effectively with the 16,000 people employed by the company.

While Vinita manages the front-end, Nilesh looks after the integral backend, including Lupin’s core research and development (R&D) and manufacturing operations, out of Mumbai. Also, with the direct responsibility of overseeing Lupin’s domestic business, he needs to deal with a field force of around 6,000 medical representatives (MRs) spread across India.

“I consider both these personalities necessary for the growth of the business; and they complement each other perfectly,” says Sharma, 69, who was the MD of the company till 2013.

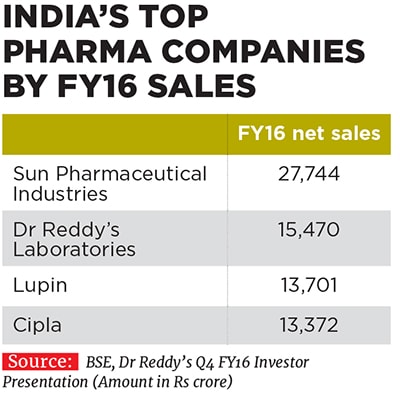

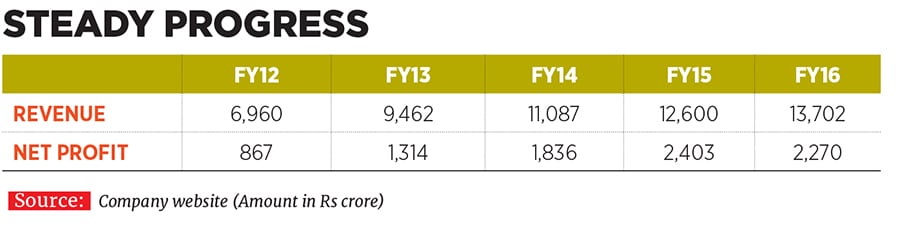

Vinita and Nilesh have been associated with their family business since 1993 and 1996 respectively, and took on their current leadership positions at Lupin in 2013. They have since helped shape the destiny of the company founded by their father Desh Bandhu Gupta in 1968 to position Lupin as one of the beacons of the Indian pharmaceutical industry (see box). Lupin ended FY16 with a turnover of Rs 13,700 crore, with a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 24 percent over the last decade since FY2006. The drug-maker’s net profit in the same period rose by 29 percent annually to Rs 2,300 crore; the operating profit margin improved from 19 percent to 29 percent; and market value ballooned from Rs 4,100 crore to Rs 66,700 crore.

Gupta senior is a proud father. For him, Vinita and Nilesh’s performance during their tenure at the helm of the company has been “excellent”. “They make a perfect duo,” says the 78-year-old Gupta, ranked 20th on the 2016 Forbes India Rich List with a wealth of $5.1 billion. “Vinita is a very social person and very entrepreneurial in the way she has been growing the business in the US. Nilesh is very hands-on and has ably handled the research and manufacturing functions.”

This synergy would be reassuring for Gupta, a former professor at the Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani, who started Lupin with the goal of making drugs to combat life-threatening diseases in India, with a seed capital of Rs 5,000 borrowed from his wife Manju. What started out as a vitamin company soon became the largest maker of anti-tuberculosis (TB) drugs in the country.

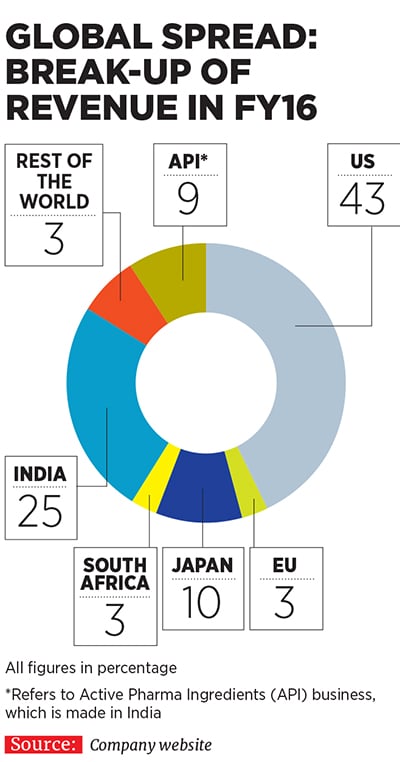

Currently, Lupin is present across diverse geographies, including the US, Japan, Mexico, Brazil, South Africa, Philippines and Europe, apart from India. In fact, as much as 66 percent of the company’s consolidated turnover came from markets other than India in FY16. Apart from TB (which is now a far smaller part of its portfolio), its products cater to therapeutic areas, including cardiovascular, diabetology, asthma, paediatrics and gastrointestinal disorders, among others.

The company made its first international acquisition to enter the Japanese market by snapping up Kyowa Pharmaceutical Industry Co Ltd in 2007. Since then, it has followed up with two more acquisitions in Japan, and others in diverse markets, including Germany, Australia, South Africa, Philippines, The Netherlands, Mexico, Russia and the US.

The rationale for these acquisitions was simple: They either needed to give Lupin access to regions in which it didn’t have a strong presence, or to new technology—in specialty products (drugs that are prescribed by specialist doctors to treat complex ailments), and in complex generics (combinations of drugs and the devices used to administer them such as nasal sprays and injectables, as opposed to regular pills).

While Lupin has acquired many small companies in the past, its decision in July 2015 to buy US-based generic drug maker Gavis for $880 million was particularly significant. For one, it was the largest foreign acquisition by an Indian pharma company to date [the second largest was Intas Pharmaceuticals’ £600 million (around $733 million) recent buyout of Teva’s generic drugs business in the UK and Ireland].

“The move to acquire Gavis was to complement our abilities in the areas of controlled substances (which are regulated products in the US that cannot be imported from outside like other generics), dermatology and gastrointestinal therapies,” says Vinita. “It would have taken us a long time if we would have tried to get into these areas by ourselves and we would have missed the market opportunity.”

Gavis also gave Lupin a much needed manufacturing base in the US from where it could cater to the local market. Vinita points out that Lupin was the only large pharma company operating in the US that didn’t have a manufacturing presence there.

With the Gavis acquisition, Lupin now has the fifth largest pipeline of products in the country. It has filed for approval with the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) for 343 products, of which it has secured 180 approvals to date. Around a third of this pipeline is on account of products inherited from Gavis. Lupin also has 256 products under development in the US, out of which 66 are from Gavis.

Not bad for a company which was a latecomer to the US market, which it entered only in 2005. Some legacy challenges in India, which involved a non-core diversification into real estate leading to a mountain of debt, prevented the company from expanding its business overseas earlier. Other Indian competitors like Cipla, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories and Ranbaxy stole a march over Lupin during this period. But the company has managed to recover ground and catch up well.

“Lupin has, over the past few years, buttressed its capability in complex generics and specialty business predominantly through the inorganic route,” analyst Vrijesh Kasera of Edelweiss Broking said in an October 2016 research report. “We estimate the US business to clock around 37 percent CAGR over FY16-18, mainly driven by ramp up in Gavis.”

Nilesh, who completed his MBA from The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania in 2002, recalls that his original plan was to work in the US for a few years after graduation, but it was Vinita who convinced him to come back and help her expand the business. “Other Indian pharma companies were doing very well in the US and Lupin was nowhere in the fray,” says Nilesh. “We had only filed some five ANDAs till then and were hungry to grow the business. I am really glad that I came back at that point and, together, we could press the accelerator as far as growing our generics business is concerned.”

To complement these plans, Lupin’s R&D spend progressively rose from 7.5 percent of net sales in FY12 to as much as 11.7 percent, or Rs 1,600 crore, in FY16.

The leadership shown by Vinita and Nilesh finds endorsement from the company’s marquee investors as well, including billionaire Rakesh Jhunjhunwala, who has remained invested in the company for 16 years. In an interview to Forbes India last year, Jhunjhunwala had reposed faith in Lupin and its “very capable and level-headed” next-generation leaders.

Desh Bandhu Gupta points out that while both of them are “strong independent leaders, what I have really been impressed with is the teamwork they have exhibited over the decades—how they complement each other and combine well to achieve strategic growth objectives. There is such a strong balance between the two.” It helps that they are an “extremely close-knit family”, says Nilesh, who has three other sisters apart from Vinita. He gives credit for this closeness to his father. The proximity that the family shares at home reflects at the workplace where Vinita and Nilesh have steered Lupin together for a decade now. “As far as the big picture about Lupin’s future is concerned, there is implicit clarity and agreement between us,” says Nilesh.

There is a certain synchronicity in the way they function, reiterates Sharma. “Very often, Vinita will make a call to Nilesh from the US, communicating a certain channel partner’s requirements, which sometimes come totally out of the blue. Nilesh quickly shuffles things around at the backend and ensures that the partner is satisfied,” he says. There is the occasional difference of opinion, Nilesh adds, and in such cases, the counsel of their father and Sharma are sought to resolve the matter.

At the heart of it is their shared goal: Growth.

Vinita says that when Lupin chalked out the plan of increasing sales to $5 billion by 2017-18, the company’s management was acutely aware that it would only be possible to grow to a certain extent organically; a gap would still need to be bridged through acquisitions. At present, 20 percent of Lupin’s overall turnover comes from the companies it has acquired, and if the drug-maker has to meet its target of doubling sales from current levels by the end of the next financial year, this proportion is bound to rise. “We are keen to acquire [more] meaningful assets,” says Nilesh. “We are figuring out what to do in Eastern and Western Europe and we’d love to acquire something in India.”

To expand its footprint in the Japanese pharma market, the second largest in the world after the US, where Lupin has a headstart over its Indian peers, the company acquired a portfolio of branded drugs from Shionogi for around $150 million in August 2016.

Fortuitously for Lupin, its balance sheet supports such growth aspirations. The company was debt free in FY14 and FY15, but had to take on some debt to finance the Gavis acquisition. Still, its debt-to-equity ratio is at a very comfortable 0.58, implying a net debt of Rs 6,700 crore.

But though Lupin may have overcome past challenges to carve a dominant position for itself in the global pharma market, there are new hurdles in sight. These include price erosion in the US due to consolidation in the supply chain; policy changes in the Indian market with an expanding number of drugs falling under the purview of NLEM (National List of Essential Medicines), prices of which are regulated by the government; a ban on several fixed-dose combination drugs in India; and regulatory scrutiny of its manufacturing operations.

But these headwinds haven’t brought worry-lines to their foreheads. “The sleeves are rolled up,” says Vinita.

In the US market, Lupin is trying to differentiate itself by focusing on niche, difficult-to-make, complex and specialty drugs, which enjoy a better margin. The Gavis acquisition was a step in that direction and plans are afoot to grow operations at the newly acquired entity.

Nilesh says Gavis hadn’t filed for any new products in the US market in the last two years. This was due to changes in the drug filing process brought in by the regulator, which made it lengthy, as well as the company’s own focus on maximising the potential of drugs already approved. “So the challenge this year was to get Gavis back to productivity from a new filings point of view and they are doing well now,” says Nilesh. “Gavis will file anywhere between 10 to 15 ANDAs in FY17. When acquiring the company we had said that we’d like to triple Gavis’s turnover in three years and we are on course to achieve that.” Its turnover has gone up from $100 million at the time to around $200 million at present, Nilesh points out.

At home in India, Lupin is trying to combat the challenges accruing from policy changes with a significant internal restructuring drive. Therapeutic divisions in the domestic business such as diabetes, gynaecology, dermatology, gastrointenstinal, cardiovascular and respiratory products, which had become too large, have been bolstered with the addition of new sub-divisions and reinforced field staff.

Between January and March 2016, Lupin added 1,000 new MRs; this is a 20 percent increase in its field strength. To emphasise the magnitude of this exercise, Nilesh points out that in the normal course of things, Lupin adds only 200-300 MRs in a year. The idea was to drive greater penetration for its products by building deeper relationships with doctors, against the backdrop of the policy changes.

Though the domestic business underperformed in the April-June 2016 quarter, registering only a 5.2 percent growth year-on-year, Lupin is willing to cut its field force some slack as it takes time to settle into a new structure and build the requisite connections among doctors, Nilesh says. And the move is paying off, according to him. The sales of Rs 931 crore reported by the domestic business in the first quarter of 2016-17 show a healthy 23.2 percent growth sequentially.

But perhaps Lupin’s biggest challenge is the nine adverse observations made by the USFDA in a Form 483 issued in March this year, after its inspection of Lupin’s Goa plant. This isn’t the first time that it has had to deal with this situation. In fact, adverse USFDA observations on manufacturing standards are a common obstacle faced by many Indian pharma companies.

A Form 483 is a communication from the USFDA to pharma companies that supply drugs to the US, conveying concerns regarding manufacturing practices. Failure to address these concerns can lead to a warning letter and eventually a ban on imports from the facilities concerned.

(Image: Joshua Navalkar)

This is the second time that Lupin’s Goa plant, most critical in its operations of making and exporting drugs to the US, has received a Form 483. The earlier one was received in July 2015, but Lupin had satisfactorily addressed the regulator’s concerns then. To mitigate this worry, Lupin has embarked on a quality transformation process. “We are dealing with aspects of quality at a very granular level by taking stock of everything from how many SOPs (standard operating procedures) there are and how these can be streamlined; what is the best way to train people in quality management; and what is the best way to prove we got the processes right,” says Nilesh. “The Goa unit will come up for re-inspection and we clearly cannot afford to have a Form 483 at that point of time.”

The Edelweiss report also notes that Lupin has a good track record of satisfactorily addressing concerns raised by the USFDA in the past.

Since joining the company, Vinita and Nilesh have benefited from the guidance of an able team of mentors comprising their father and Sharma, who joined the company as a professional manager, but is more like family now to the Guptas.

Sharma says that the most important lesson that he has tried to impart to his mentees has been the art of forecasting events that are likely to shape business and envisioning plans to deal with the changing dynamics of an organisation that is growing in size.

And Vinita and Nilesh have been good students, as evidenced by Lupin’s performance over the last few years. Their diligence has, in fact, made the $5 billion target appear within reach. After all, as the septuagenarian Gupta puts it, “Numbers are an outcome of the hard work you put in.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X