Bellatrix Aerospace: Reimagining space mobility and satellites-as-a-service

Having persevered for a decade, Rohan Ganapathy and Yashas Karanam are on the cusp of breaking out Bellatrix Aerospace as an important spacetech venture from India

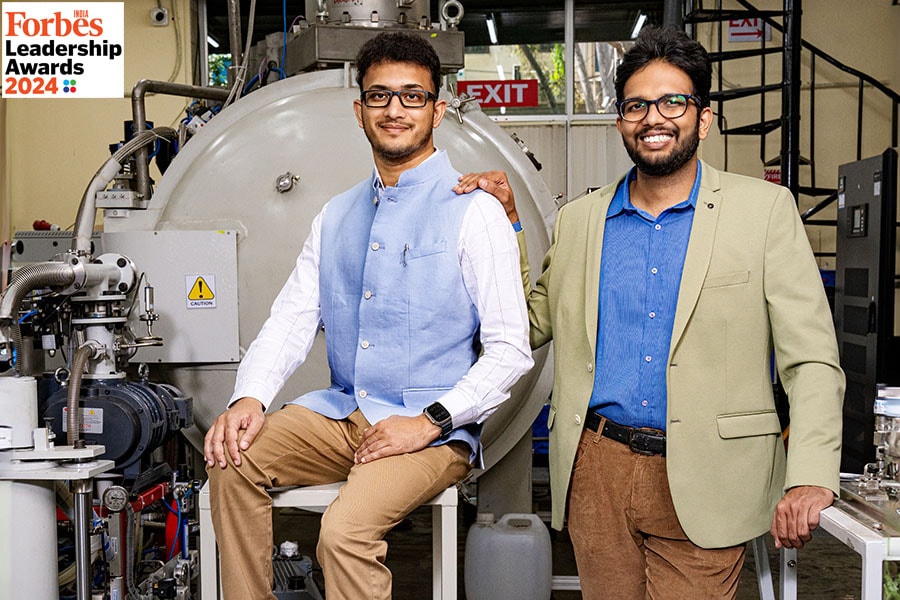

Yashas Karanam (right), and Rohan Ganapathy of Bellatrix Aerospace Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

Yashas Karanam (right), and Rohan Ganapathy of Bellatrix Aerospace Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

More than 10 years ago, a letter from the late Abdul Kalam touched off an entrepreneurial journey for Rohan Ganapathy and Yashas Karanam that became Bellatrix Aerospace, which last year launched its first tech demonstrator in-space propulsion system.

Bellatrix wasn’t named for the evil character in the Harry Potter series. “We named it after the star in the constellation Orion. That’s where we want to head, maybe say 500 years from now,” Ganapathy says.

In 2012, still in college, his initial goal was to do something that would get him a seat in one of the Ivy League universities. He’d been inspired by a visit to the Goddard Space Flight Center in the US and a chance to meet Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin.

Back home, he teamed up with two juniors at college to build an engine that would run on water as a propellant. They didn’t have the money, and weren’t able to raise any. When a well-wisher brought word to Kalam about Ganapathy and his interest in spacetech, the former president asked to meet him.

Kalam couldn’t help with money, but he wrote them a recommendation letter, in 2013, which opened doors. JSW Steel offered a grant of ₹20 lakh, which allowed them to rent a garage and work on their project after college into the wee hours of the morning.

Karanam was Ganapathy’s friend, their families knew each other, and his interest in entrepreneurship was complementary. In 2015, Ganapathy’s project to build a prototype engine that used water as a propellant worked, and it was the year they incorporated Bellatrix officially as a private limited company.

Karanam was Ganapathy’s friend, their families knew each other, and his interest in entrepreneurship was complementary. In 2015, Ganapathy’s project to build a prototype engine that used water as a propellant worked, and it was the year they incorporated Bellatrix officially as a private limited company.

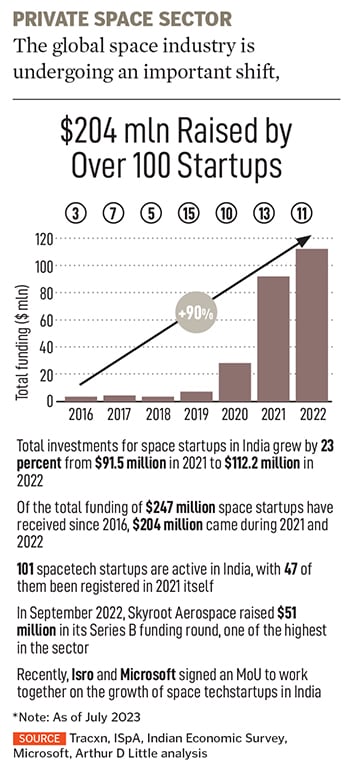

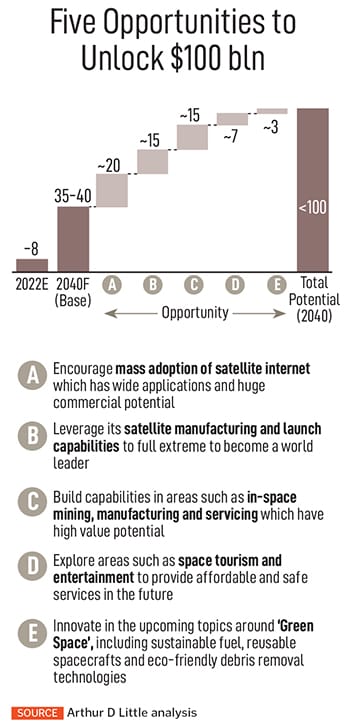

The nascent spacetech startup ecosystem in India, helped by the liberalised space economy rules and supported by Isro, is an example of this shift. And, with the right initiatives, India could tap this shift to go from a $8 billion space economy to $100 billion by 2040, according to the consultancy.

The nascent spacetech startup ecosystem in India, helped by the liberalised space economy rules and supported by Isro, is an example of this shift. And, with the right initiatives, India could tap this shift to go from a $8 billion space economy to $100 billion by 2040, according to the consultancy. Even countries like Australia that were dependent on the US for a long time have started creating their space programmes, allocating their own budgets, and India, which has already done that, has a lead, he points out. “Now it’s just a question of how much further we want to go. It comes down to how much Indian policymakers are willing to invest in space to either do it independently or to do it with other countries.”

Even countries like Australia that were dependent on the US for a long time have started creating their space programmes, allocating their own budgets, and India, which has already done that, has a lead, he points out. “Now it’s just a question of how much further we want to go. It comes down to how much Indian policymakers are willing to invest in space to either do it independently or to do it with other countries.”