Sunil Vachani: In a relentless pursuit of excellence for global domination

After becoming the largest electronics manufacturing services company in India, Sunil Vachani now wants Dixon Technologies to transform into a global powerhouse

Sunil Vachani, Executive chairman, Dixon Technologies

Image: Amit Verma

Sunil Vachani, Executive chairman, Dixon Technologies

Image: Amit Verma

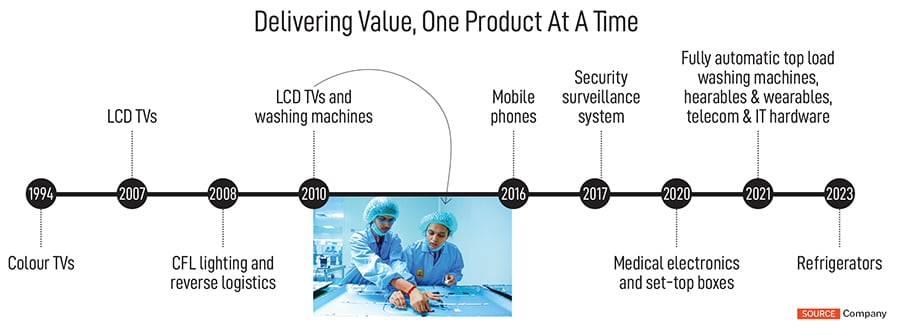

In 2022, Sunil Vachani’s vision for Dixon Technologies was for it to become the largest electronics manufacturing services (EMS) company in India. Two years later, Vachani is beaming with pride as this milestone has been achieved. “My vision has expanded. Now, I want Dixon to emerge as an engineering powerhouse,” he says, as we sit at Dixon’s wholly owned subsidiary Padget Electronics’ new 1.3 lakh sq ft smartphone manufacturing facility in Noida. He wants the company to be one of the top 10 global EMS companies in the next five years, and top five in the next 10 years.

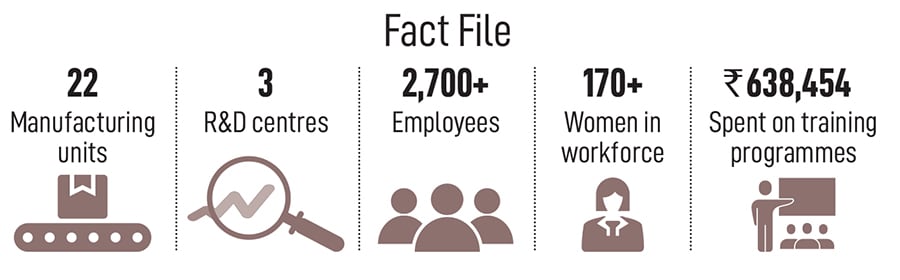

“But for this to happen, a lot will have to change,” reckons the co-founder and executive chairman. There are plans for heavy investments in infrastructure capabilities, backward integration and skill development of the workforce. Over the last two years, close to five new manufacturing units have been added and a mega campus of close to 1 million sq ft is in the works. “To become globally competitive, you need scale. This will help us achieve that,” he says.

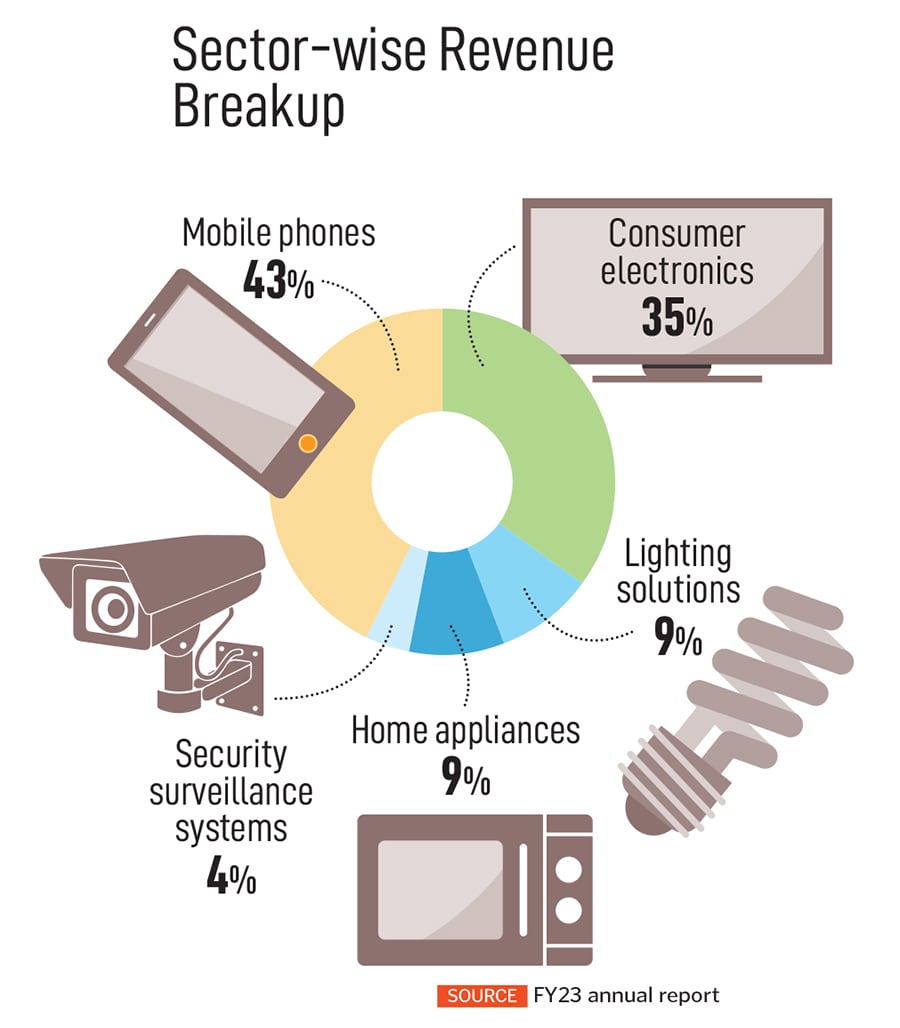

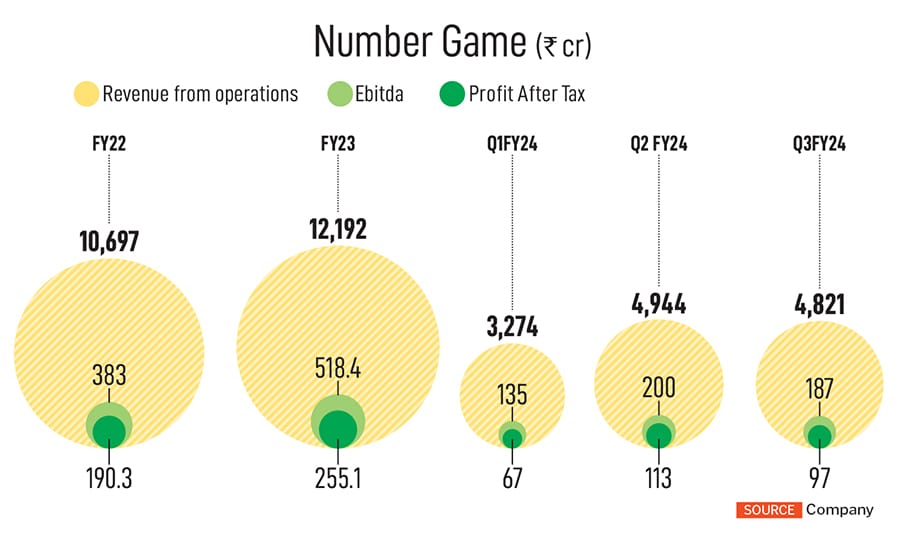

The company has clocked a turnover of ₹12,192 crore in FY23, approximately a 90 percent growth compared to its revenue of ₹6,448.2 crore in FY21. Its market capitalisation stands at ₹37,921 crore and, over the last one year, its share price has increased by over 135 percent (as on February 14).

Given its strong financial performance and strategic decisions that have helped the company and industry grow, 55-year-old Vachani is the Entrepreneur of the Year at the Forbes India Leadership Awards 2024.

“Vachani is a forward-looking leader with a strategic vision and a relentless pursuit of excellence. His adeptness in navigating dynamic markets, adopting new manufacturing practices, and cultivating robust partnerships has been instrumental in Dixon’s successes,” says Muralikrishnan B, president, Xiaomi India.

In the early 1990s, after completing his Associates in Business Administration from American College, London, Vachani returned to India. He could have joined the family business, but he wanted to do something on his own. Thus, began his tryst with entrepreneurship. And through all these years, a piece of his father’s advice stayed with him: “Always have a microscopic and telescopic vision at the same time. You need to keep an eye on the big picture, but at the same time, not miss out on the small details.”

In the early 1990s, after completing his Associates in Business Administration from American College, London, Vachani returned to India. He could have joined the family business, but he wanted to do something on his own. Thus, began his tryst with entrepreneurship. And through all these years, a piece of his father’s advice stayed with him: “Always have a microscopic and telescopic vision at the same time. You need to keep an eye on the big picture, but at the same time, not miss out on the small details.”