Wagh Bakri: Brewing a slow and steady growth story

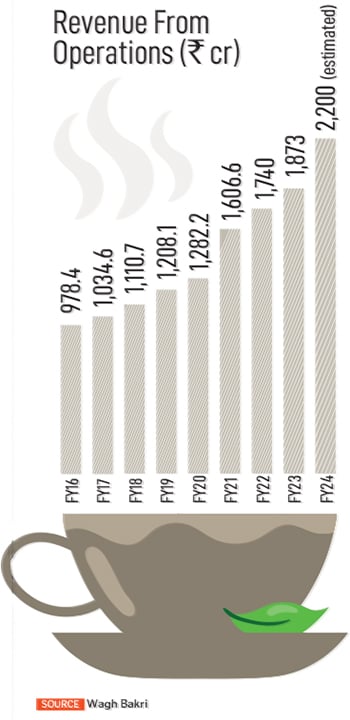

Wagh Bakri has never focussed on growth at breakneck spread, yet it remains the third-largest packaged tea company

(From left) Priyam Parikh, whole-time director, Rasesh Desai, vice chairman and managing director, Paras Desai, executive director, Vidisha Parag Desai, director, Wagh Bakri Tea Group

Image: Mexy Xavier

(From left) Priyam Parikh, whole-time director, Rasesh Desai, vice chairman and managing director, Paras Desai, executive director, Vidisha Parag Desai, director, Wagh Bakri Tea Group

Image: Mexy Xavier

On a Saturday afternoon, as we enter the two-storeyed Wagh Bakri tea lounge in Ellis Bridge, Ahmedabad, a houseful of customers are enjoying warm cuppas in the relatively mild winter of January. We sit down for a conversation with the three generations of the family, but something feels incomplete. The most enthusiastic and outspoken member isn’t around. 2023 was a tough year for the Desai family, with the passing of, first, Pankaj and later Parag Desai within six months. In October, 49-year-old Parag met with an accident and succumbed to multiple complications.

A week later, his wife, Vidisha, decided to fill in the shoes and took charge. While she wasn’t involved in the business earlier, things were not new either. “I used to accompany him on most business trips and international fairs where he wanted me to take the lead and speak about our brand and explain business processes,” reminisces Vidisha, who is getting hold of the day-to-day operations gradually.

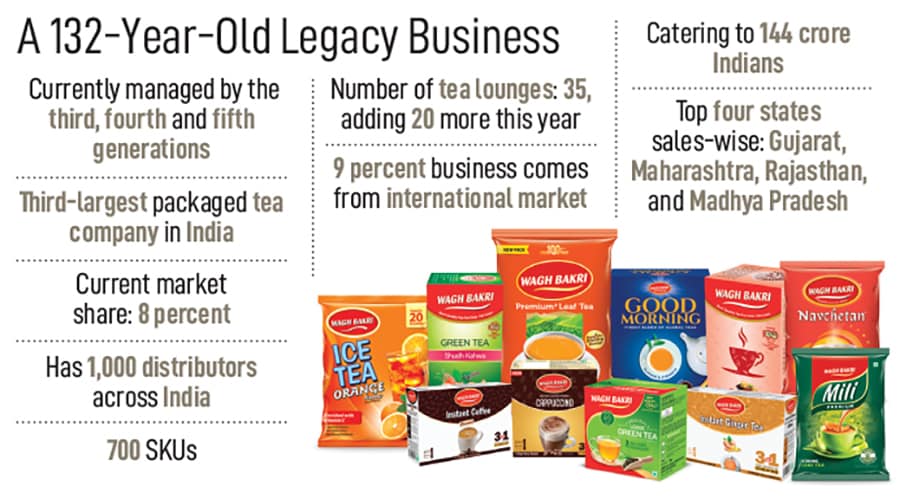

While the world moves at lightning speed, 132-year-old Wagh Bakri Tea Group still believes that slow and steady wins the race. The brand rules the hearts of 144 crore Indian tea drinkers today and has been clear about its business ethos from day one. Quality, customer satisfaction, and brand value have helped it not only earn loyal customers but also the badge of the Regional Goliath.

“We never had this thirst to become a regional or national leader. Our single focus has been our customers,” says Paras Desai, executive director of Gujarat Tea Processors and Packers Ltd (the parent company of Wagh Bakri). It was only in 2000 that the Ahmedabad-headquartered company became the leader in Gujarat, after eight decades of its existence in India.

“We never had this thirst to become a regional or national leader. Our single focus has been our customers,” says Paras Desai, executive director of Gujarat Tea Processors and Packers Ltd (the parent company of Wagh Bakri). It was only in 2000 that the Ahmedabad-headquartered company became the leader in Gujarat, after eight decades of its existence in India.

Just a day before the interaction, the legacy brand founded by Narandas Desai celebrated its 105th year in India. In 1892, he started the tea business by leasing 500 acres in Durban, South Africa. But racial discrimination forced him to follow his mentor, Mahatma Gandhi, back to India in 1915. He sailed back home with a certificate signed by Gandhi, which read, “I knew Mr Narandas Desai in South Africa, where he was for a number of years a successful tea planter.” This served as a token of help to ease migration in the homeland. And there was no turning back thereafter.

With more than 1,000 distributors across India, the brand has over 700 SKUs and products ranging from masala chai, tea bags, green tea, and ice tea to even coffee and tea premix. To keep up with the times, the company also started offering gourmet tea priced between ₹700 and ₹900 for 50 grams, with offerings like tranquil berry tea, milk oolong tea, and matcha tea.

With more than 1,000 distributors across India, the brand has over 700 SKUs and products ranging from masala chai, tea bags, green tea, and ice tea to even coffee and tea premix. To keep up with the times, the company also started offering gourmet tea priced between ₹700 and ₹900 for 50 grams, with offerings like tranquil berry tea, milk oolong tea, and matcha tea.