How MTR has stayed true to its Kannadiga core

Over 17 years after its acquisition by Norwegian company Orkla, MTR has stayed true to its core—a Kannadiga brand rooted in local culture, cuisine, and revenue. As it steps into its centenary year, it has spiced up its broader appeal but remains a regional Goliath

(left)Sunay Bhasin, CEO, MTR Foods and Sanjay Sharma, CEO, Orkla India Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

(left)Sunay Bhasin, CEO, MTR Foods and Sanjay Sharma, CEO, Orkla India Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

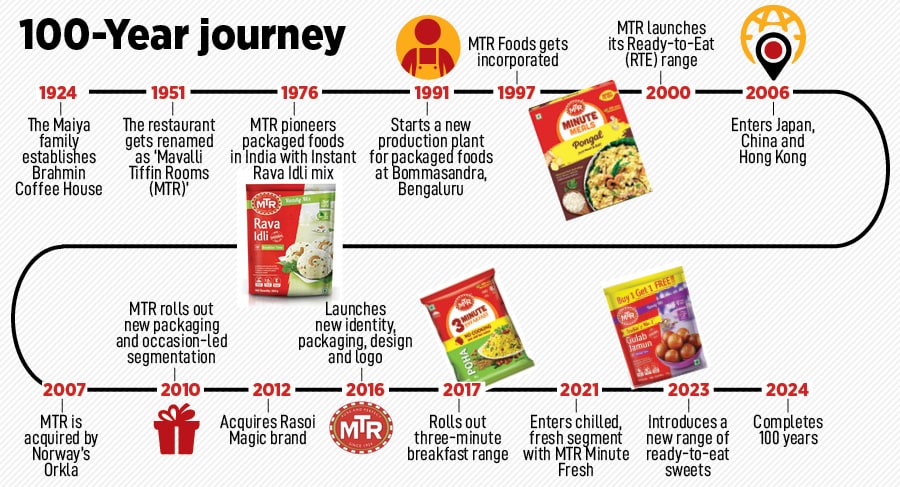

Sanjay Sharma was gripped with a comical predicament. “It was strange for a Punjabi to head a 99 percent Kannadiga business,” recalls the chief executive officer of Orkla India, alluding to his role of heading spices and foods brand MTR as CEO in 2009. “I mean, we are two different cultures,” says Sharma, who started his professional innings with Voltas in 1990 and managed Pepsi Snacks Foods (in the early 90s, Voltas used to be the distribution arm of Pepsi Snacks Foods). Over the next one-and-a-half decade, he had stints with Colgate Palmolive and Dabur, and, in 2009, Sharma wafted across the south of Vindhyas to Bengaluru to head heritage brand MTR, which traces its origin to 1924 and was acquired by Orkla in 2007.

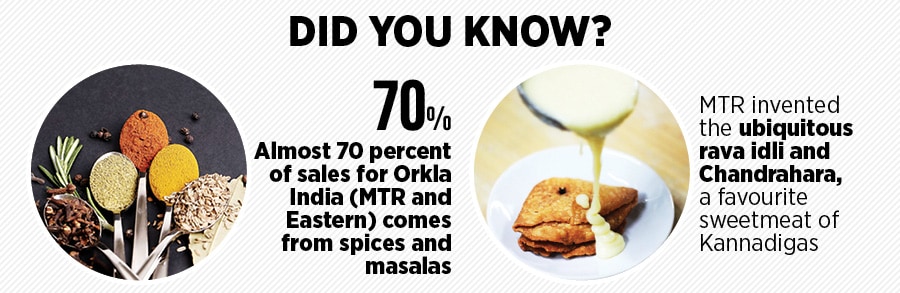

Two years after the buyout, Sharma was at the helm of a quintessential regional brand that prided itself in its rich cultural lineage and DNA. MTR—it invented the ubiquitous rava idli and Chandrahara, a favourite sweetmeat of Kannadigas—was synonymous with Karnataka. For Kannadigas, MTR was not a brand but an emotion. Sharma knew the context, the ask and the new task. “My biggest challenge was to change myself, respect the culture and know more about the company and people,” he recounts.

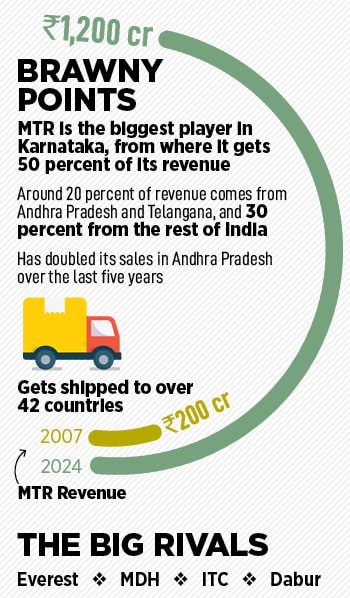

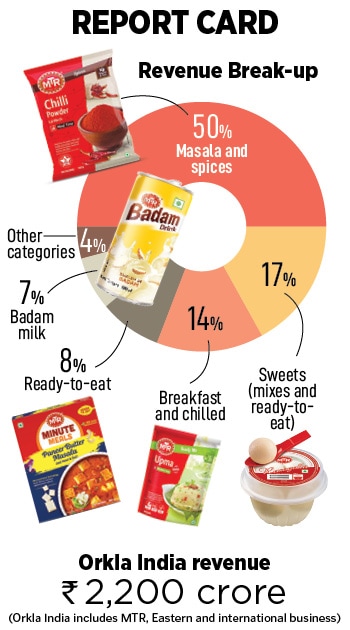

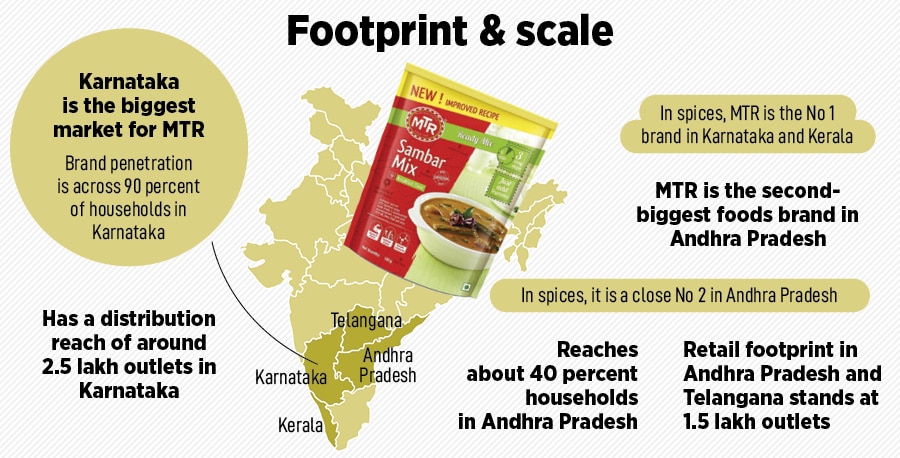

What also made the job intimidating was the way Sharma was wired. Voltas, Colgate and Dabur were national brands that drew power from their sweeping pan-India retail heft. MTR, in contrast, was largely confined to Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and a few adjoining Southern states despite its presence across the country and a few countries where it catered to the Indian diaspora. The top dog embraced the new reality, acknowledged the new business landscape, and factored in another reality which was the driving force behind Orkla’s acquisition of MTR, which had around ₹200 in revenue in 2007. “When Orkla bought MTR, it did not see a national business in it. It saw a regional business,” he reckons. The Norwegian investment firm had a strong regional strand ingrained in its DNA: Buy and build local brands. With MTR in its fold, Orkla was unambiguous in its game plan: Go deep rather than spread wide.

Back in 2007, MTR, undoubtedly, was a dominant regional player. In spices and masalas, it was the biggest brand in Karnataka. “We were the No. 2 brand in Andhra Pradesh. Both Karnataka and Andhra were our strong markets,” he says, adding that MTR also had a national trophy to flaunt. It was the biggest player in ready-to-eat gulab jamun in India. Sharma had his task cut out: Dump national aspirations and keep MTR a strong regional player sharply focussed on Karnataka and adjoining states.

Back in 2007, MTR, undoubtedly, was a dominant regional player. In spices and masalas, it was the biggest brand in Karnataka. “We were the No. 2 brand in Andhra Pradesh. Both Karnataka and Andhra were our strong markets,” he says, adding that MTR also had a national trophy to flaunt. It was the biggest player in ready-to-eat gulab jamun in India. Sharma had his task cut out: Dump national aspirations and keep MTR a strong regional player sharply focussed on Karnataka and adjoining states.

Seven years later, in 2016, another Punjabi from the land of chhole bhature and lassi was venturing into the territory of rava idli and ellu juice (sesame seeds milkshake). Sunay Bhasin too had his reality check. One of the first things he learnt was that sambar (a lentil stew), unlike idli, in South India tastes radically different from the one made in the North. Bhasin—he worked with Britannia, KFC and Pizza Hut, and joined MTR as chief marketing officer in 2016—had an erroneous perception about sambar. He thought sambar powders of all kinds and from all places would be the same. “Sambar would taste the same because sambar powder is the same. Right? Wrong,” he says.

(This story appears in the 09 August, 2024 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

If downplaying the identity of the new owner came in handy, then conveying the ambition unambiguously also helped. “We wanted to remain regional. We didn’t want to become a large company in India,” he says. In terms of the pantheon of the pan-India FMCG companies in size, MTR sits pretty at 42nd place. The talking point too remained MTR. “We never talked about Orkla. We made it clear that our purpose was to grow MTR, and make it bigger in its home states,” he says.

If downplaying the identity of the new owner came in handy, then conveying the ambition unambiguously also helped. “We wanted to remain regional. We didn’t want to become a large company in India,” he says. In terms of the pantheon of the pan-India FMCG companies in size, MTR sits pretty at 42nd place. The talking point too remained MTR. “We never talked about Orkla. We made it clear that our purpose was to grow MTR, and make it bigger in its home states,” he says.

The heritage brand from Karnataka, reckon marketing and branding experts, has created a new playbook for managing acquisitions. One of the big strengths of a big brand is its ability to scale at a furious pace. “You buy to grow, and most of the new owners yield to the temptation of taking the acquired brand beyond the home turf,” says Ashita Aggarwal, professor (marketing) at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. The acquired brand, she adds, is a trophy to be flaunted, and spreading it far and wide gives it bragging rights. “Orkla interestingly stayed away from this,” she says. The new owners quickly realised the brand had a massive headroom for growth on its home turf. By some accounts, Karnataka’s population is equivalent, if not bigger, to the UK. “If you have bought the biggest food brand in Karnataka, it means you have bagged the biggest in the UK,” she says.

The heritage brand from Karnataka, reckon marketing and branding experts, has created a new playbook for managing acquisitions. One of the big strengths of a big brand is its ability to scale at a furious pace. “You buy to grow, and most of the new owners yield to the temptation of taking the acquired brand beyond the home turf,” says Ashita Aggarwal, professor (marketing) at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. The acquired brand, she adds, is a trophy to be flaunted, and spreading it far and wide gives it bragging rights. “Orkla interestingly stayed away from this,” she says. The new owners quickly realised the brand had a massive headroom for growth on its home turf. By some accounts, Karnataka’s population is equivalent, if not bigger, to the UK. “If you have bought the biggest food brand in Karnataka, it means you have bagged the biggest in the UK,” she says.