How the 146-year-old Crompton has managed to stay afloat

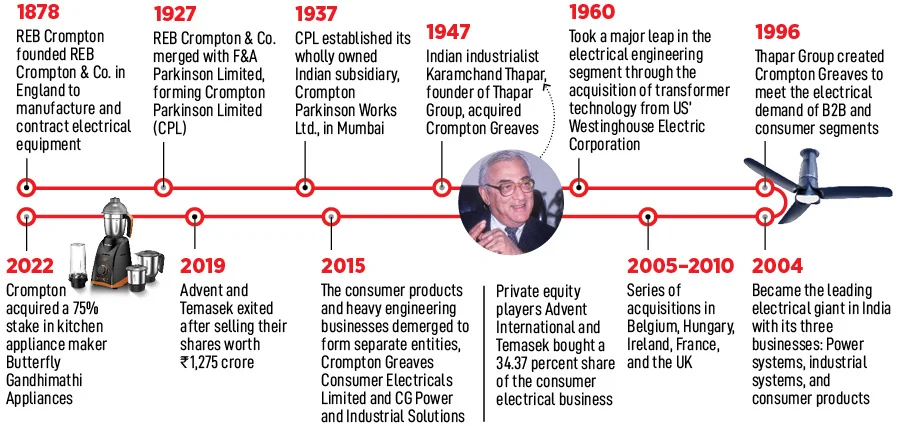

The company has seen a series of mergers, demergers, acquisitions and exits over its life of nearly a century and a half. Here's how the company that was founded in 1878 became a household name in the 21st century

Crompton has manufacturing plants in Gujarat (pictured here), Goa, Maharashtra and Himachal Pradesh

Crompton has manufacturing plants in Gujarat (pictured here), Goa, Maharashtra and Himachal Pradesh

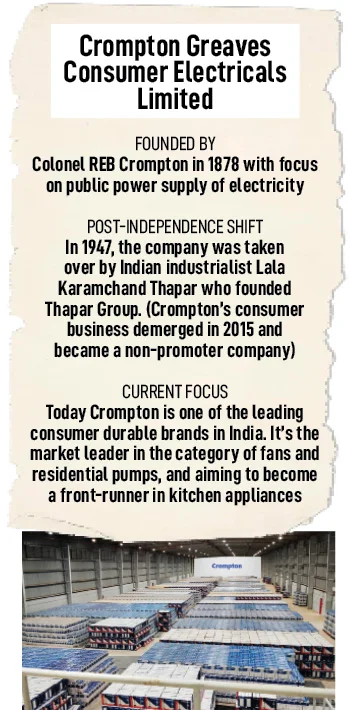

When Colonel REB Crompton established Crompton in 1878, little did anyone imagine that the brand would survive for 146 years to become a household name in the 21st century.

It all began in 1947, when industrialist Karamchand Thapar of the Thapar Group—known for acquiring businesses the British couldn’t sustain during World War II—took over Crompton. The family-owned business succeeded in putting India on the global map with multiple acquisitions and quick expansion.

But after 2013, things started going downhill. With the majority of the fresh acquisitions funded through debt, the capital-intensive businesses started sinking and borrowings piled up to ₹7,500 crore in March 2014. Soon, the business was on the verge of bankruptcy under third generation Gautam Thapar’s leadership. He put up Crompton Greaves for sale to clear the mounting dues and demerged the consumer electrical, power, and industrial solutions businesses.

The consumer business—contributing more than one-fifth of Crompton Greaves’ combined revenue with products like fans, pumps, and lighting—was also supporting the B2B businesses. It found a suitor in April 2015. Private equity players Advent International and Temasek bought a 34.37 percent share of the consumer electricals business for ₹2,000 crore. Multiple promoters later, the newly formed Crompton Greaves Consumer Electricals Limited (CGCEL) was now in the hands of professionals.

The brand was losing its sheen because it had been underinvested for years. Competition was intensifying, and companies like Havells were climbing up the ladder. “Although Crompton had a strong brand image, market leadership started eroding eventually. The company built a lot of trust and equity among its channel of retailers and distributors, which remained intact. Plus, it was still profitable but needed transformation,” says Mathew Job, who joined the new board as CEO in 2015 and quit last year after serving for seven years.

The brand was losing its sheen because it had been underinvested for years. Competition was intensifying, and companies like Havells were climbing up the ladder. “Although Crompton had a strong brand image, market leadership started eroding eventually. The company built a lot of trust and equity among its channel of retailers and distributors, which remained intact. Plus, it was still profitable but needed transformation,” says Mathew Job, who joined the new board as CEO in 2015 and quit last year after serving for seven years.