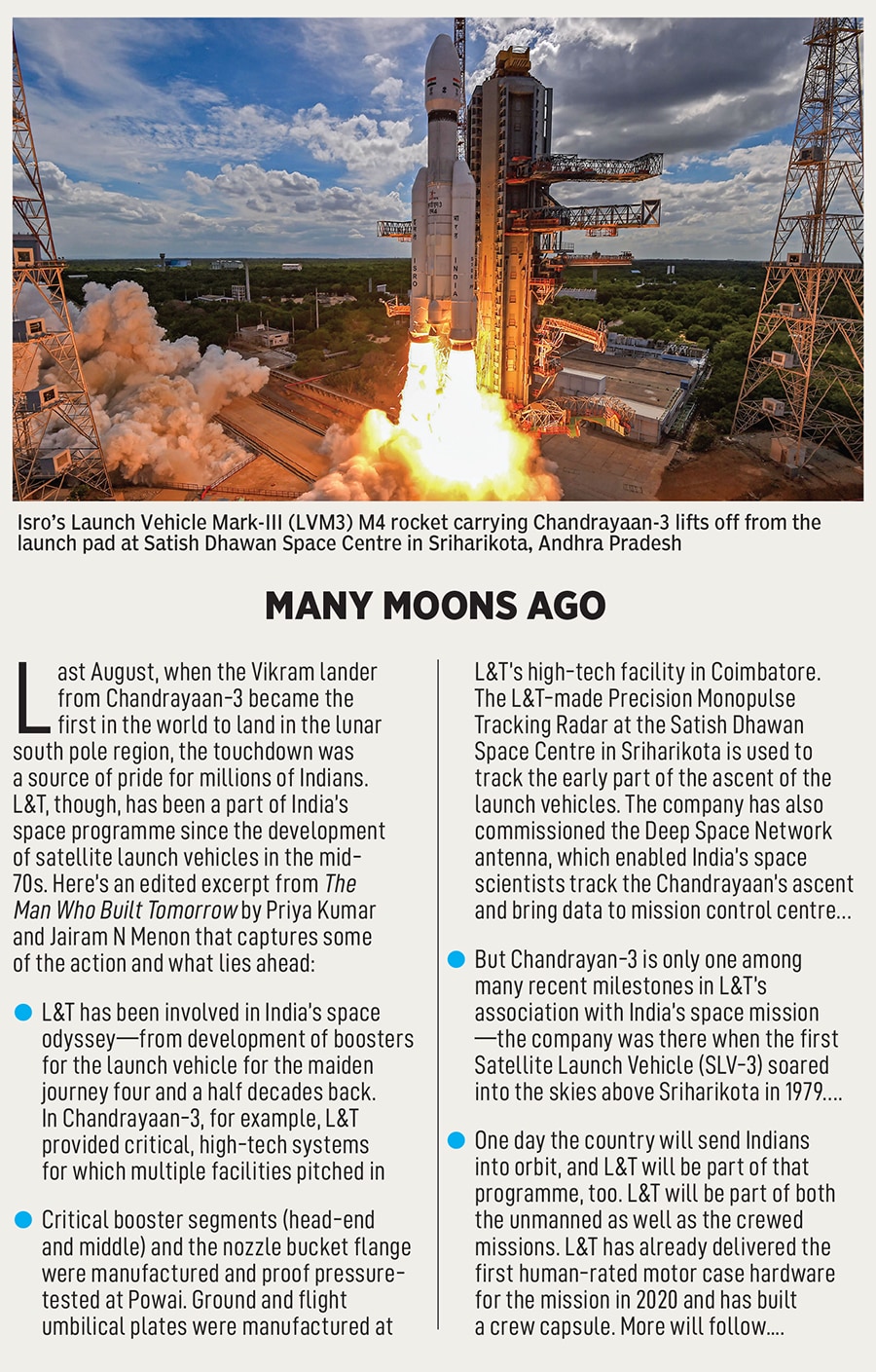

L&T and the growth of a self-dependent India after 1947

Larsen & Toubro began its India sojourn in Independent India to help build the nation. Along the way, employees and shareholders also gained from the nuclear reactors, nuclear-powered submarines and space satellite systems that it makes

AM Naik, former executive chairman, Larsen & Toubro

Image: Courtesy Larsen & Toubro Ltd.

AM Naik, former executive chairman, Larsen & Toubro

Image: Courtesy Larsen & Toubro Ltd.

On a drizzly July afternoon, AM Naik is at the head of the table at his office-cum-residence in the ‘High Trees’ bungalow in Bandra’s leafy Pali Hill in suburban Mumbai. Behind him three flags —two Tricolours and the Larsen & Toubro (L&T) bright yellow flag with the logo in bold black at the centre—lend the room a hue that embodies what the 82-year-old chairman emeritus of the engineering and infrastructure colossus stands for: Passionate commitment to country and company.

“Today I am happy for what I have done for my country. I am happy for creating the new L&T. And now I am happy that I am helping people,” says the man who joined the company as a junior engineer almost 60 years ago, and who now spends most of his time on his pet philanthropic projects in education, skill-building and health care.

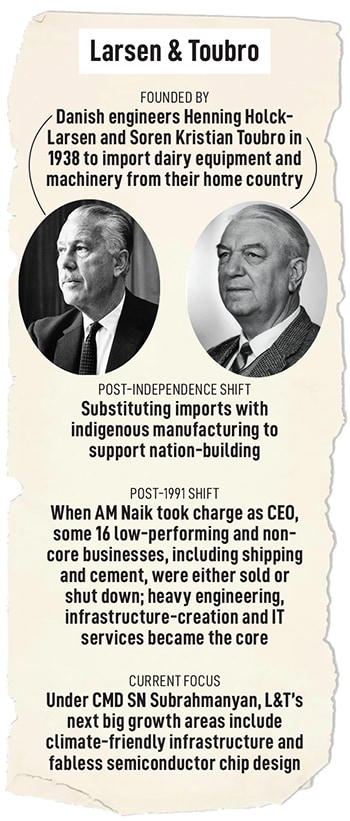

If Naik is synonymous with the ‘new L&T’, 1.0 dates to pre-Independence when two Danish engineers, Henning Holck-Larsen and Soren Kristian Toubro, started the partnership company in 1938 out of a cubicle in the then-commercial district of Bombay, Ballard Estate. As R Gopalakrishnan and Pallavi Mody write in How Anil Naik Built L&T’s Remarkable Growth Trajectory (Rupa, 2020), “Little did they know then that they were making this hot, humid and dusty foreign land their karmabhoomi.”

What started as an equipment and machinery import business—beginning with dairy—turned into an opportunity to manufacture once World War II broke out in 1939; imports from countries like Germany, Denmark and Norway (the last two were invaded by the Germans) were banned. Repairing and refitting war-struck ships also became a prospect, along with replicating machinery that was hitherto imported. “Engineering and innovation were the two pillars on which the partners took their first baby steps,” write Gopalakrishnan and Mody.

What started as an equipment and machinery import business—beginning with dairy—turned into an opportunity to manufacture once World War II broke out in 1939; imports from countries like Germany, Denmark and Norway (the last two were invaded by the Germans) were banned. Repairing and refitting war-struck ships also became a prospect, along with replicating machinery that was hitherto imported. “Engineering and innovation were the two pillars on which the partners took their first baby steps,” write Gopalakrishnan and Mody.

The bigger opportunities for growth came with Independence, with L&T by then becoming a company with a Danish name, but “wholly and Indian company in equity, emotion and inspiration”. In 1948, 55 acres of undeveloped marsh and jungle land in the central Bombay suburb of Powai were acquired to create the main manufacturing hub, by when offices had come up in Calcutta, Madras and New Delhi.

(This story appears in the 23 August, 2024 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)