In the limelight: Pratik Gandhi, 15 years in the making

Scam 1992 has opened the floodgates for Pratik Gandhi in Bollywood. But it's taken the actor over 15 years, and a strong foundation in Gujarati theatre and cinema, to earn national recognition

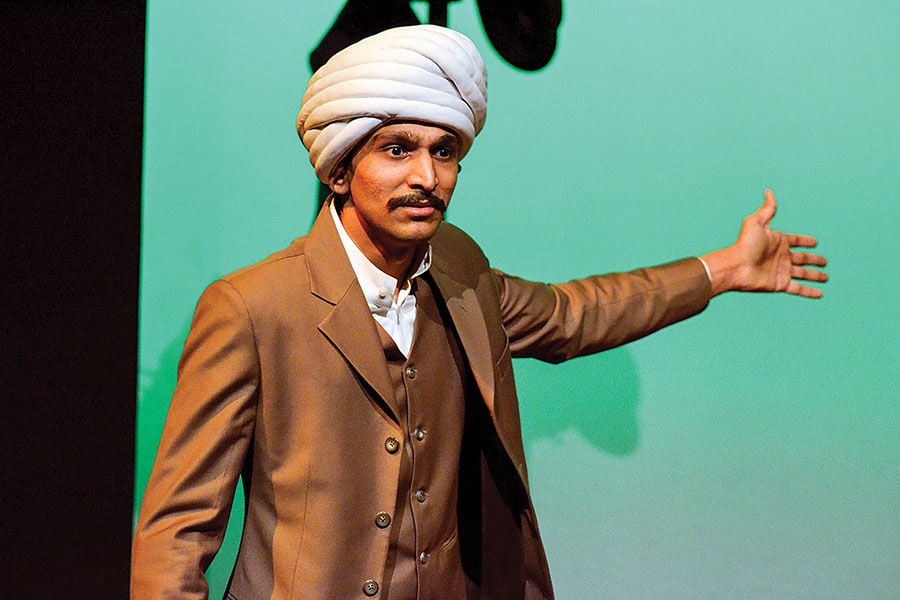

Pratik Gandhi, Indian theatre and film actor. Photo by Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India

Pratik Gandhi was shooting for a Gujarati web series in a no-connectivity zone near Gir National Park in Gujarat in January when a few children requested the actor to pose for photos with them. He was surprised to hear that they had watched his web series Scam 1992, in one corner on their terrace—the only place where the show streamed perfectly on their mobiles, despite network issues in the region. It’s almost ironical that the man who once sold pre-paid SIM cards of Hutchison Essar and later convinced customers to convert them to post-paid connections in his hometown Surat was now a national star because of the internet boom and content consumption on over-the-top (OTT) platforms.

The success of Scam 1992—a 10-episode web series based on the life of ‘Big Bull’ Harshad Mehta—has given Gandhi the mainstream recognition he had been longing for. The 40-year-old has been on a signing spree over the last couple of months: He’s scheduled to start filming a Hindi movie with actor Taapsee Pannu later this year; is shooting for director Tigmanshu Dhulia’s screen adaptation of Vikas Swarup’s Six Suspects; and has given his nod to a Gujarati film with wife Bhamini Oza. His overnight popularity seems like a fairy tale, but for the holder of a diploma in mechanical engineering and a degree in industrial engineering, it’s been a wait of more than 15 years.

ROLE PLAY

Gandhi, the son of teacher parents, came to Mumbai in 2004 to become an actor. “I wanted to do something big in this industry. I desired to carve my own space… where people will watch something in my name,” he says. It was easier said than done, especially for an outsider whose only achievements were performing on stage in school since the age of four, and doing local theatre in Gujarat. Yet, the lanky youngster believed in himself. It was a time when India’s Best Cinestar Ki Khoj, a television show to discover new talent, had premiered on Zee TV, and a couple of Gandhi’s friends from Surat had cracked three rounds with one of them ending up as a finalist. He thought work would be easy to come by, but what he had to endure was a struggle to survive in a competitive and expensive city like Mumbai.

After staying with his cousin for three months, Gandhi and his brother Punit rented a small house in an old housing society in Vile Parle (East). With a monthly rent of Rs 6,500 as additional expenditure, the actor could not afford to wait for an acting opportunity. He began scanning newspapers for job advertisements while keeping his hope of finding work in theatre alive. After spotting a vacancy for industrial and production engineers, including fresh graduates, he emailed the National Productivity Council (NPC), but it bounced twice in the days of dial-up internet. He was third-time lucky, though, and bagged freelance projects for the company.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)