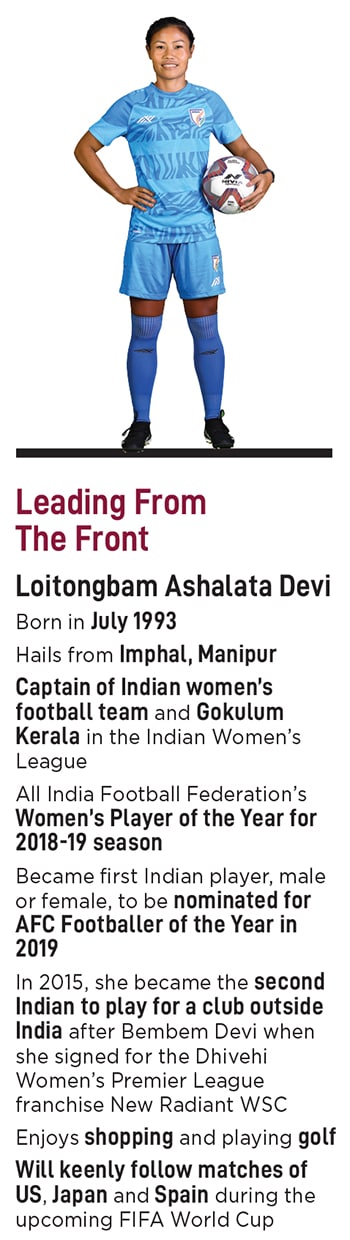

Loitongbam Ashalata Devi: Inspiring the new generation of Indian footballers

In life and in sport, Indian women's football team captain Loitongbam Ashalata Devi has relentlessly pursued her dreams, despite the challenges, and wants to inspire more girls to play the game

Loitongbam Ashalata Devi says it takes a lot of hard work to maintain success

Image: Courtesy AIFF

Loitongbam Ashalata Devi says it takes a lot of hard work to maintain success

Image: Courtesy AIFF

Loitongbam Ashalata Devi shed copious tears on the ground when the under-17 squad for the national football team was announced in 2008. It was a bittersweet moment for the girl from Imphal, Manipur. After years of toil, struggle and a battle against family pressure to give up the game that she had taken a liking to, she was a step closer to representing India. Her emotions, though, had less to do with being overwhelmed about her own selection. The teenager felt bad that some of the players—from different states across the country—with whom she had shared some priceless moments during a three-month camp prior to the announcement had not made the cut. “I did not know that feeling… I was happy as well as sad,” says Loitongbam.

The pain of being deprived of something you feverishly wish for was something she could relate to. In the mid-noughties, when she was in class seven, she saw some boys play football near her house. She hadn’t seen any girl do the same. At Ramananda High School, where she studied, there was a tournament for boys, but none for girls.

So, the youngster requested her teacher to organise one. She formed a team, as advised, and eventually played against the boys—wearing a crepe bandage-like anklet, not studs, that her uncle had bought for ₹25. Their team won with Loitongbam scoring during the penalty shootout along with a few others. “I was elated. The fact that I was one of those who scored made me delirious… that’s when I realised that I have never been so happy. And I decided to play the sport,” she says about her first experience of the game.

At home, however, her family was vehemently opposed to the idea of their daughter playing football. “My mother beat me a lot after that game,” recalls Loitongbam, adding that she stopped playing for a couple of months due to the fear of getting thrashed. The separation, though, became difficult to digest and she resumed playing the sport without informing her mother. “But she got to know where I was after school and beat me up again,” reminisces the captain of the Indian women’s football team and someone regarded as one of the best defenders in the game today. Upon realising that it was futile to stop her adamant daughter, her mother gave up, but with a strict caveat. “She said don’t ask for money from me for your studs, jersey… and even if I did, I did not get any,” says the 29-year-old whose paternal uncle, who was secretary at a sports club nearby, supported her and enrolled her with a local club.

At home, however, her family was vehemently opposed to the idea of their daughter playing football. “My mother beat me a lot after that game,” recalls Loitongbam, adding that she stopped playing for a couple of months due to the fear of getting thrashed. The separation, though, became difficult to digest and she resumed playing the sport without informing her mother. “But she got to know where I was after school and beat me up again,” reminisces the captain of the Indian women’s football team and someone regarded as one of the best defenders in the game today. Upon realising that it was futile to stop her adamant daughter, her mother gave up, but with a strict caveat. “She said don’t ask for money from me for your studs, jersey… and even if I did, I did not get any,” says the 29-year-old whose paternal uncle, who was secretary at a sports club nearby, supported her and enrolled her with a local club.

The value of money and time was something that Loitongbam, one of six siblings, understood at a young age. After her farmer father passed away in 2011, running the house became a challenge. Three of her sisters were studying in college that was some distance away and Loitongbam herself needed money to travel—the football ground was an hour-and-a-half away from home—for practice. Though her uncle had ensured a slow patch-up between mother and daughter over playing football, the financial strain was too much for the housewife to handle. She reiterated that her daughter give up the game, study well and get a job to support the family.