The Michelangelo of Zardozi

From crafting masterpieces to sacrificing his eyesight for an embroidered opus depicting Moses, a zardozi artisan's story lives on in the lanes of Agra with younger generations taking the legacy forward

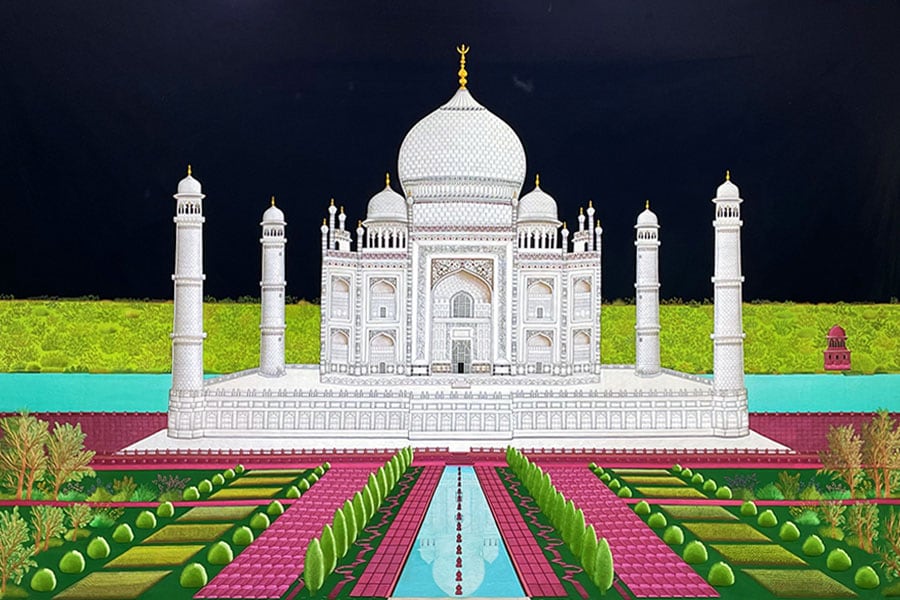

Reshamdozi and Sheesh Mahal techniques flourish in the hands of talented embroiderers at Sham’s Zardozi workshop in Agra.

Image: Veidehi Gite

Reshamdozi and Sheesh Mahal techniques flourish in the hands of talented embroiderers at Sham’s Zardozi workshop in Agra.

Image: Veidehi Gite

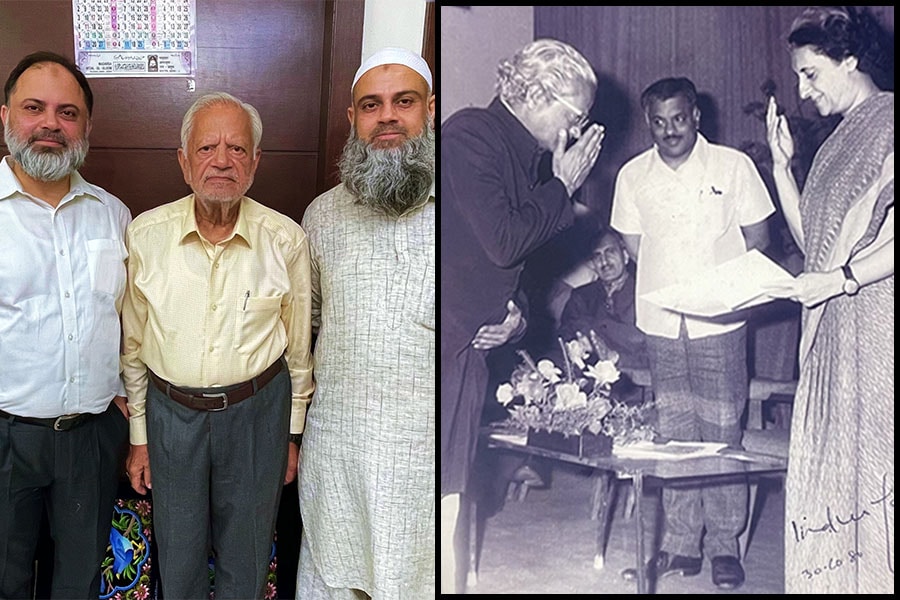

Zardozi, originally introduced to India by Nur Jahan, the 20th wife of Mughal emperor Jahangir, along with marble inlay work and perfumery, has a rich history. And that history comes alive in the labyrinthine alleys of Basai Khurd, adjacent to Shiv Kothi in Agra, at the humble abode of late Sheikh Shamsuddin. Fondly referred to as Shams, he is renowned for his role in resurrecting the art of zardozi and stands as the sole innovator in India credited with pioneering the technique of 3D zardozi embroidery. In present day, Faizan Uddin, his grandson, carries the torch of a legacy that reshaped the landscape of Indian embroidery.

As with all legacies in Agra, the family's lineage traces back to the principal architect of the Taj Mahal. "Our connection to Ustad Ahmed Lahori spans 16 generations, a heritage we cherish," Faizan says. Reflecting on his family's evolution, he adds. “Our ancestors were architects, and it's often remarked that by the third generation, the work changes. As times changed, so did our craft.”