Unparalleled passion: What makes Northeast India the talent factory of football

Northeast India, a football-crazy region, has produced some of India's finest players. Forbes India travels to Mizoram to understand the passion for the sport, the support from government and private institutions, and why it needs better infrastructure

The Regional Sports Training Centre in Saidan, Kolasib—a picturesque football ground with an artificial grass turf

Image: Mexy Xavier

The Regional Sports Training Centre in Saidan, Kolasib—a picturesque football ground with an artificial grass turf

Image: Mexy Xavier

About 90 km from Aizawl lies Kolasib, the smallest district in Mizoram, with an area of 1,386 sq km. The district, with a population of roughly 24,000, has five football academies and four grounds, but these are still not enough to cater to the demand for the sport. “We’ve started using smaller futsal grounds now for football practice as the bigger ones are almost always booked,” says R Lalruatfela, founder and coach of the privately-run Four4Two academy.

Around 2.30 pm, we reach the Regional Sports Training Centre in Saidan, Kolasib—a picturesque football ground with an artificial grass turf, overlooking the city on one side and mountains on the other. Soon, young students from the academy start jostling in. Aged between 10 and 14, they are dressed in oversized jerseys, shorts that are long enough to be trousers, knee-length socks and studs. The moment the coach brings a massive net bag with 10-15 footballs, the group of 25 players run towards him, screaming with excitement. They divide themselves into smaller groups and begin practice even before the coach’s instructions.

This is just one of the many instances that depicts the passion for football, among kids and adults, not only in Kolasib and Aizawl, but across the Northeast. Though the ‘Seven Sisters’ are starkly different from each other in many aspects, the one thing in common among them is football, and how ingrained it is in their culture.

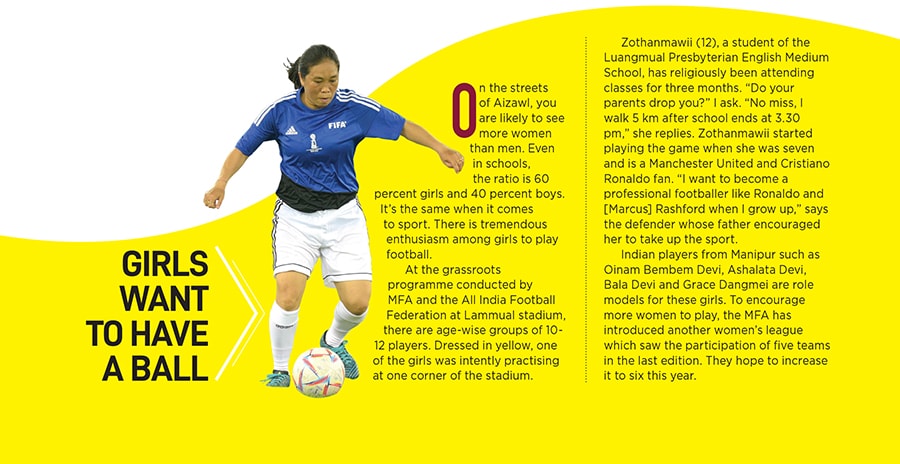

Nothing exemplifies this more than the football fervour that has gripped the region ahead of the FIFA World Cup. On the streets of Aizawl are multiple sports shops mostly selling football gear; television stores are offering discounts for the World Cup and local grounds are full of men and women playing football at any time of the day.