Ajay Piramal's Wealth Finds a Purpose in the Piramal Foundation

Ajay Piramal, through the Piramal Foundation, is practising what he preaches about the need for the privileged to 'share'

As Pratap Singh’s voice booms through the phone, it is easy to imagine him as the stereotypical school headmaster walking around with a stick in hand and children scattering like chicken at the first glimpse of the ‘big bad wolf’. And that may well have been the case till sometime ago. But for the past three years, the headmaster of the Rajkiya Balika Uchh Prathamik Vidyalay, a government girls’ school in the Churu district of Rajasthan, would like to believe things have changed.

“If I think of myself as a government servant and that this is a government school and that I can’t do anything differently, then that would be negative thinking,” says the 53-year-old. Instead, he has been trying to engage with students and teachers in a manner that is accessible and friendly. “I have to see things from their perspective,” Singh says. He has introduced up to 20 different kinds of ‘activities’ that have made teaching and studying more enjoyable in the school.

The proof of the pudding is in the vindication from students like Meenkashi Godra of Class 8 in his school. She says, “There has been a lot of change in the last two years.” Of late, her teacher has been teaching her favourite subject, mathematics, through games. “Now I can understand better.”

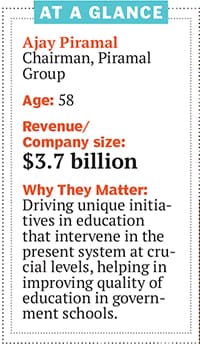

Around 1,400 km away, at his group’s headquarters in Mumbai’s Lower Parel, Ajay Piramal would be pleased to hear this. For the past eight years, the chairman of the $3.7 billion Piramal Group has been keeping a close watch on the initiatives taken by Piramal Foundation, set up in 2008.

“We are privileged, and have everything that it takes. But there is a need to share,” says Piramal, 58, who was ranked 41 in Forbes India’s 2013 Rich List, with a personal wealth of $1.55 billion. “India’s challenges are many.” Piramal has focussed on a range of verticals such as health care, education, livelihood creation and youth empowerment.

An initiative that stands out is in the area of education. Called The Piramal Foundation for Education Leadership (PEL), this might seem an obvious step for Piramal: His grandfather Seth Piramal Chaturbhuj Makharia had set up Rajasthan’s first school for girls in the Bagar town of Rajasthan’s Jhunjhunu district as also the state’s first school that admitted harijans (now categorised as a scheduled caste). He would be impressed with PEL’s efforts to train headmasters of government schools in order to improve the quality of school education in rural India.

“A study by Pratham [a leading NGO involved in education] shows that more than 50 percent of Class 5 students can’t write a sentence in their mother tongue. Also, half of these students can’t do basic mathematics,” says Paresh Parasnis, head, Piramal Foundation. This, “despite huge amounts of money spent by the Indian government that had helped increase enrolments in schools but hadn’t improved the quality of education,” adds Rajeev Sharma, associate professor at IIM-A’s Ravi J Matthai Centre for Educational Innovations.

Pratap Singh spent three years at the foundation, attending two training workshops annually (each lasting four days). Through the year, a ‘fellow’ from the foundation comes to Singh’s school and spends 16 days with him following up on the progress and doing required ‘course correction’. There has been a marked difference in Singh, personally and professionally. “My children tell me I’m now a better papa and my wife tells me I’m a better husband,” he says cheerfully. Equally important, the results in his school have been positive.

His school was among those surveyed by the foundation to understand the impact of the leadership training of headmasters. “In Churu, we saw a 46 percent improvement in language proficiency of children. In mathematics, the improvement was 26 percent,” says Aditya Natraj, director, PEL.

The idea of focusing on headmasters was conceived when Piramal was attending a presentation by Natraj at Pratham in 2007. Natraj, a chartered accountant who left a corporate job in London to join the NGO, was talking about the importance of training headmasters. “Usually senior teachers are made headmasters. But a headmaster needs a completely different skill set,” says Natraj.

This is especially true for a headmaster in rural India where caste dimensions make matters complex. Most of the students in these government schools come from poor families, and their parents are not equipped to guide them. “The headmaster has to deal with them and also with politics and corruption,” adds Natraj. To make matters worse, headmasters are not the most motivated lot. “They are not going to get any rewards for doing a good job and, even if they do, they can be transferred to a different school,” says Sharma. But it is also a fact that given the high social standing of a headmaster, he or she could become the catalyst to improve the quality of education in government schools.

Piramal was convinced. He asked Natraj to design a programme for Piramal Foundation. Natraj studied systems in the US, the UK and was particularly impressed by the Dutch experience where the local community selected the principal of its local school; the principal, in turn, chose the teachers. Piramal told Natraj, “Let us do for teacher training in India what the IIMs have done for management and what the IITs have done for engineering.”

They framed the content for this process with the help of IIM-A’s Sharma, his colleague Neharika Vohra, and Bodh Shiksha Samiti in Jaipur, an organisation that specialises in training teachers. The training was divided into four parts: Personal, instructional (with respect to students), organisational (with respect to fellow teachers) and social (with respect to the larger community).

Piramal wanted to expand the programme as soon as possible. In 2008, the foundation signed a memorandum of understanding with the Rajasthan government to launch a pilot project in Jhunjhunu. It attracted 250 applicants, from which 100 headmasters were selected. Piramal’s instruction to the team was strict: “I want to see results within a year.” The businessman himself financed the pilot project, which initially had a yearly budget of Rs 2 crore.

As part of the programme, the initiative to attract bright young minds that have just graduated from college proved to be a massive plus. Called the Piramal Fellowship, youngsters sign up to spend two years in rural India. After their training, they become the link between the foundation and the headmasters. Each ‘fellow’ is instrumental in ensuring that headmasters execute what they learn, and measuring its impact.

In the process, the fellows—who earn a stipend of Rs 14,000 a month—get an inside view of rural India and a closer understanding of issues facing it. As part of the training, they live with a family in their designated area for a fixed time without pocket money and mobile phones. The intention is to immerse themselves in the conditions faced by their subjects.

“It has been a life changing experience,” says Teesta Mukherjee, a former fellow who now works in PEL’s HR department. A student of international relations from Jadavpur University in Kolkata, Mukherjee’s high point was working with the Christian headmistress of a school in Ahmedabad. While most of the students were Muslims, the teachers were Hindu. “It was a tough situation as the principal was refusing to take any initiative. But in two years, the principal had changed enough to celebrate both Ramzan and Raksha Bandhan on the same day in the school,” says Mukherjee.

SCALING UP

Piramal, who spends about 15 percent of his time with the foundation, wants to scale up all the initiatives in order to have maximum impact. Consequently, PEL is currently training 700 headmasters, who are helped by about 200 fellows. In December 2013, Piramal opened a 45,000 sq ft PEL campus in Bagar; it can house up to 200 people.

But the entrepreneur understands that the problem is too big for just one person. Rajasthan itself has about 60,000 government schools. The country has 1.5 million. So, he has decided to share his foundation’s learning and get in as many partners as possible.

PEL has also gone beyond Rajasthan. In Gujarat, it trains headmasters in Surat and Ahmedabad, aided by a Rs 3 crore-a-year grant from the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation. PEL also trains headmasters in Mumbai’s government schools. Here, Unicef, the Godrej Group and the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation are partners. “We are also working with other business groups, including the Murugappa Group, the Lalbhai Group and the Godrej Group, to help start similar initiatives,” says Natraj. Piramal’s own contribution, through his corporate arm, is about Rs 10 crore a year.

Given Piramal’s international network (he is a member of the Board of Dean’s Advisors at Harvard Business School), international collaborations have already started. Harvard Global Education Innovation Initiative has chosen PEL has its Indian partner (there are seven other institutes from across the world). This means access to global best practices even as PEL shares its own learnings. The Piramal initiative has also tied up with New York University for assessment of ‘non-cognitive skills in India’. A tie-up with University of South Carolina is in the offing. The new campus in Bagar, Piramal’s hometown, will also increase its offerings. Apart from leadership training for headmasters, it plans to start higher level courses—for instance, master’s programmes—in education.

Back in Churu, Pratap Singh is working on this vision for his school. Like his own children who have enrolled for higher studies, Singh wants the students at his school to think big. As for himself, he says, “I will retire in 2020. But I won’t be tired.”

And Piramal will consider even that a job well done.

‘Hire professionals and give them a say’

Ajay Piramal

Traditional management vs modern practices

I have seen how my father practiced, and that was traditional management. From him I learned about entrepreneurship, about taking risks and how to empower young people to take bigger responsibilities.

Modern management comes through specialised education and being advised by leading consultants. I went to Jamnalal Bajaj Institute of Management Studies and Harvard Business School. Leading consultants like McKinsey and Accenture are advising us. I try to balance the two.

Professionalisation of management

Professionalisation is very important. It is important to bring in talent and put it in the most appropriate jobs. We have recruited the best in global talent.

At the same time, it is important to listen to this talent. They should have a say in decision-making. Professionalism also means more systems and processes as you grow and to have more structural planning.

Biggest influences

My father has been a big influence. But he passed away when I was young.

Nitin Nohria, the dean of Harvard Business School, has been a big influence. He has given insights on how to take risks and how to think big and to be quick in decision-making—on how we can have a positive impact on the world around us.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)