Mining The People's Share

The government wants mining firms to share a quarter of their profit with the people they displaced. The move has sparked off a debate

Infographics: Sameer Pawar

It has been a nerve-wracking battle between mining companies and the people displaced by their projects in India. The government’s tokenism has not been able to help either side. Several mining projects are held up because the people who would be affected by them are now protesting. At the same time, there has been little relief in the lives of those displaced by earlier projects. This sorry saga has now entered a new phase.

The government wants mining companies to set aside 26 percent of their profits for the welfare of the indigenous people affected by their projects. This proposal, part of the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Bill, 2010, will be in addition to the regular corporate income tax.

Expectedly, this has miners up in arms. They have just come out of a commodity slump and were hoping to reap the benefits of a recovery. Mineral prices have gained enough to raise hopes of a return to the peak rates seen in early 2008. And the new tax threatens to spoil their party.

“Which company can afford to pay 26 percent of its profits as tax year after year?” asks R.K. Sharma, secretary general of the Federation of Indian Mineral Industries (FIMI). He points out that the government already charges 10-15 percent as royalty.

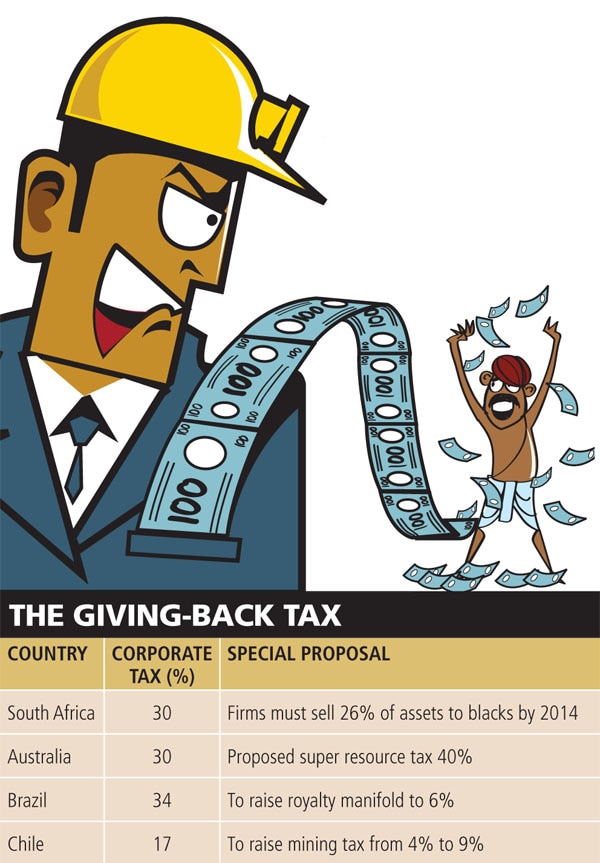

But the proposal is not an entirely new one. “A number of mineral-rich countries have been following it for years without impacting the genuine profitability of their mining companies,” says Chandra Bhushan, deputy director of New Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment (CSE).

Recently, an industry outcry followed Australia’s plan to levy a 40 percent “resource super profit tax” on the local mining industry, the third largest in the world. The debate was so intense that it led to the incumbent prime minister losing his job. But the inspiration for the Indian government comes from South Africa’s 2004 mining charter that promotes black ownership of natural resource companies. According to it, mining companies must sell 26 percent of their assets to the blacks by 2014, and thereby compensating for the apartheid hardships.

A senior executive at Sesa Goa, the country’s largest private iron ore miner, says the government’s intention is right but questions if adding one more layer of tax is the solution. “The money generated through mining royalties runs into thousands of crores. Is there any clarity on how much of this is used to develop the marginalised population? Implementation is the key, not a new tax,” he says.

More grey areas exist. For instance, would only private miners pay the tax? Steel minister Virbhadra Singh has asked for “special consideration” for state-owned companies like NMDC. “And how will you compute the 26 percent from mining profits whose mines are for captive use?” asks Pradeep Maheshwari, a mining consultant.

In a country where tax evasion is high, implementation of the new policy would be very difficult, according to a tax expert. “It doesn’t stop a company [from playing] around with its balance sheet and [showing] smaller profits,” says Ravishankar Raghavan, principal in the tax group at law firm Majumdar & Co.

But most miners tacitly agree with the principle of affirmative action aimed at the displaced population. It is well known that mining in India has not benefitted those displaced by it. Raghavan says that the government may well ask mining firms to set apart 10-15 percent of their profits for local development, but must give them the benefit of tax deduction. “This would make sure that the companies do not have too much of a tax burden,” he adds.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)