Steeling up for a Tough Target

India is chasing a goal of 120 million tonnes of steel by 2012, but it would first have to get past red tape

The steel mills in India are rolling to life again. All major companies in the sector have recorded at least a 50 percent jump in sales for the first three months of the financial year. Excited at this unexpected bright spot in the industry, union steel minister Virbhadra Singh announced the sector’s capacity will double to 120 million tonnes by 2012. But what are the factors that need to fall in place for capacity to double?

On the face of it, India has all the ingredients to speed up its output from the current 65 million tonnes a year. It has raw materials — coal and iron ore — in plenty, competent human resource and with fast economic growth, enough capital and a big market. In fact, points out former managing director of Tata Steel, Dr. J.J. Irani, “Even now the Indian economy can use about 100 million tonnes of steel, given the economic growth.”

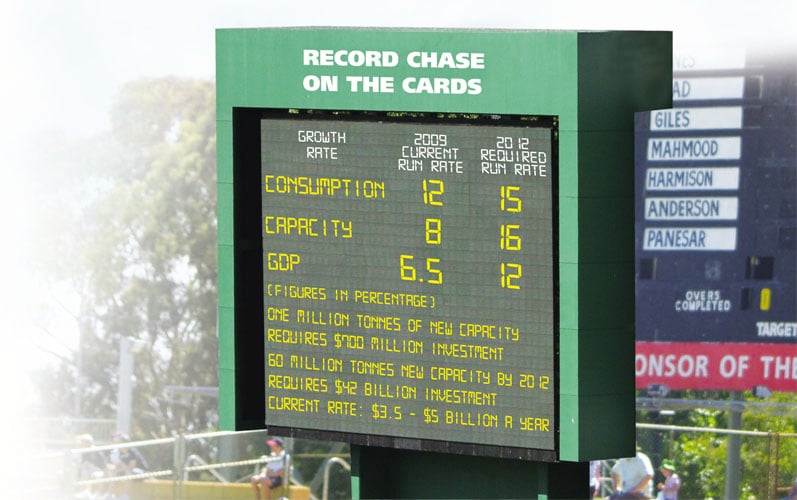

Now, the hurdles. Irani notes that there is a 1.2 percent growth in steel industry consumption for every 1 percent increase in GDP. Unfortunately, even if the Indian GDP grows by an unlikely 10 percent per annum in the next three years, we won’t get to 120 million tonnes (see graph).

But, what really holds back the steel industry is the lack of will from the Indian administration to unlock the logjam involving new steel projects in the country.

Over 50 projects to build new steel plants with a total capacity of almost 75 million tonnes are yet to see the light of the day due to delay in getting clearances.

That includes South Korean giant POSCO, India’s Tata Steel and the world’s largest steel company, ArcelorMittal. All have projects held up in Orissa and Jharkhand, each with a capacity of six to 12 million tonnes. According to Tata Steel’s agreement with the Orissa government, the company needed to put in place 25 percent of the equipment for the project before it got the lease for iron ore mining. Though the company has met the commitment, it is yet to get the lease. Orissa steel minister Raghunath Mohanty did not respond to calls.

But it’s not just the bureaucracy that’s to blame. The private sector is hesitant to scale up now because demand for steel is uncertain. A lot of the projects have been stalled because of a lack of transparency with regard to rehabilitation of people who will be displaced because of the mines and factories. In Orissa for instance, the roots of the present protests over various plants lies in the poor track record of similar projects since the 1950s for resettlement and rehabilitation (R&R).

In fact, of all the projects, Tata Steel’s Orissa plant might be the only one that is yet to take off because of regulatory hurdles.

Irani believes that India can get to the 120 million tonne mark, but it’ll need a miracle in the form of administrative willpower. One could add financial stability, positive demand outlook and better R&R policy to that list of prerequisites. Without that, the 120 million tonnes by 2012 target might remain a pipe dream.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)