JCB: Hitting Pay Dirt in India

JCB�s strategy of taking the retail route in India has paid rich dividends, but can it protect its turf in the wake of more intense competition?

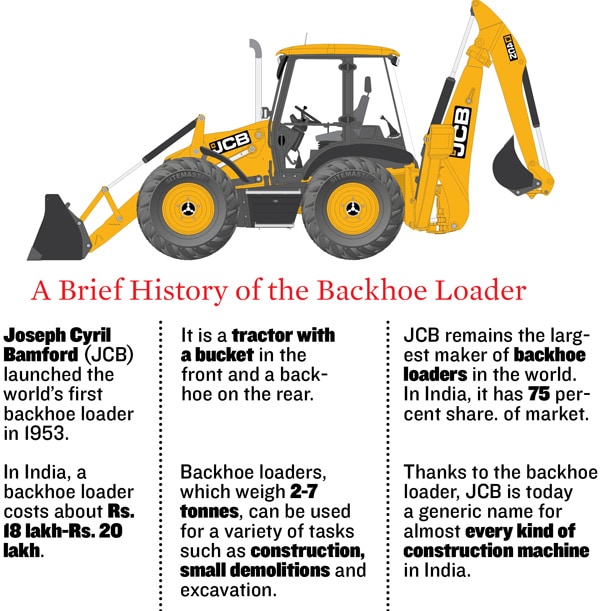

About an hour’s drive from South Delhi lies Ballabgarh, the industrial belt just inside Haryana. Among the scores of manufacturing units there, is the world’s largest plant to make backhoe loaders (a tractor-like vehicle with an arm and bucket mounted on the back and a loader mounted on the front). The plant, which can produce up to 100 of these two-tonne machines a day, is a prized possession of the UK-based construction machinery maker JCB. And every morning when Vipin Sondhi, the managing director and CEO of JCB India, takes the one-hour drive from his house to the unit, he remembers a tough decision that he and his boss in London, JCB Chairman Anthony Bamford, took three years ago. And every morning he feels vindicated about it.

“We were planning to expand this facility,” recounts Sondhi as he sits in his office, situated in the middle of the facility that was set up in 1979. The expansion had started in 2007, but the economic slowdown a year later put a question on the viability of the nearly Rs. 300-crore investment. Should the expansion be paused? “But we were sure of the Indian infrastructure story in the long term. Our chairman shared the vision and we went ahead with investment,” says Sondhi.

Today, he can look back and smile. The last three years have been among the most successful for the company. The Indian market is today the largest for the Staffordshire-based company. While it’s present in 150 countries, of the total 51,600 machines that JCB sold globally last year, 21,000 were in India. Its revenues rose almost 10 times from Rs. 450 crore in 2001 to Rs. 4,429 crore in 2010. That is a shade less than one-third of the parent’s total revenues of $3.2 billion.

“Overall, every second construction machine sold in India today has JCB’s yellow stamp on it,” says a proud Sondhi, who joined the company in 2006. Before that, Sondhi headed Tecumseh Products India, the American compressor maker. At JCB India, the icing on the cake for Sondhi was when earlier this year the unit became the first in India to sell one lakh construction machines. Apart from backhoe loaders and excavators, JCB also sells other construction machinery like pick and carry cranes.

Globally, the company trails others like Caterpillar and Komatsu. Even in other emerging markets, it’s a relatively new player in Brazil and faces stiff competition from local companies in China. “JCB India is a very important part of the JCB Group,” says Anthony Bamford. “We continue to invest heavily in India… It’s a success story that we’re very proud of in the JCB Group,” he adds.

JCB’s success comes at a time when new players like Mahindra & Mahindra are entering the field and old partnerships are being re-looked. This March, Dutch major CNH Global bought out its stake in its join venture, which makes backhoe loaders, with Indian engineering giant L&T. The move, say industry watchers, will see a more aggressive CNH in the market.

This means that despite the success, JCB might be on the verge of facing its toughest competition yet. Can Sondhi, who is often credited with making the backhoe loader a backbone of India’s construction industry, help JCB protect its turf? But first, a little more about JCB’s success.

Leading The Field

About 80 km away from Ballabgarh is Sonepat, home to Ajmer Singh. From the time the 38-year-old farmer set his eyes on a backhoe loader more than a decade ago, Singh has been calling it ‘JCB’. Singh had rented it to move earth on his fields. Singh likes it and likes it so much that today he owns eight ‘JCBs’.

Not all are backhoe loaders though, some are excavators. Singh rents them out, at rates ranging from of Rs. 600 an hour to Rs. 9,500 a day, and earns more than he ever did from his farming.

Sondhi loves listening to these ‘JCB love stories’. Backhoe loaders suit the Indian working style, he says. “Indians tend to sweat their assets and backhoe loaders are versatile machines, capable of doing various kinds of work and can travel anywhere,” says Sondhi. Backhoe loaders are mainly used in excavation, digging and levelling. But with attachments, the same machine can be used to mop floors and even drill holes. And in India, one can also see the machines transporting people!

Also, the construction sector in India is still in the developing stages, which means scale is still to build up. That makes the comparatively smaller backhoe loader the most popular choice and the right kind of machine to make a retail product out of.

But JCB’s spectacular success is recent. Until 2003, it was selling less than 3,000 machines a year. It was only by 2004, in its 25th year in India, that the company reached 25,000 machines. The next 75,000 though came in seven years. The spark was most likely provided by a partial change in management in 2003.

That year, JCB parted ways with its local partner Escorts. The Delhi-based company, known for its tractors, said it wanted to get out of “non-core” businesses. As events in later years showed, the “non-core business” was not the only reason, at least for the backhoe loader business. In little more than a year of its non-compete clause with JCB expiring in 2008, Escorts re-entered the segment with a new backhoe loader brand Digmax.

The break-up though, suited the multinational company. It was now fully in control.

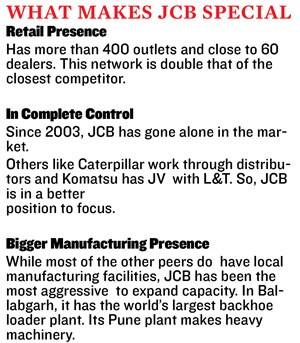

“The Golden Quadrilateral project had taken off and India was on the verge of a big infrastructural push. We saw tremendous increase in volumes,” says Sondhi. To capture that demand, JCB took an unusual route. In a market where other big multinationals like Caterpillar and Komatsu focus on institutional clients, JCB took the retail route. Under Sondhi, the company aggressively expanded its reach and has doubled its outlets to more than 400 within six years.

When Ajmer Singh bought his first machine in 2000, the only outlet for construction machinery in the region was JCB’s, 200 km away in Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. More than seven years later, when he bought an excavator, Ajmer could choose from five JCB outlets in Haryana alone, including one in Sonepat itself. The company also went to nooks and corners of the country. “We have 100 percent market share in Ladakh!” exclaims Amit Gossain, vice president, marketing & business development.

The outlets themselves got a facelift. While earlier they functioned out of dealers’ home and shops, now each of them had dedicated real estate. And in Sondhi’s words, the outlets became JCB’s “hands and ears”. For instance, not only did Ajmer Singh get finance from the outlets for the buy, if there was any problem or breakdown, service men from a JCB outlet would reach the site within a few hours. Interestingly, while JCB’s employee strength is 1,500, its 53 dealers employ close to 5,500 people. “We also have a mobile repair unit that travels to the most interior places where these machines are used,” says Amarpreet Anand, director of A&A Earthmovers, JCB’s dealer for western Uttar Pradesh and Uttaranchal.

Maruti-like

JCB’s retail muscle mirrors car maker Maruti’s dominance of its sector in India. Sondhi agrees that the company has followed the “auto footprint”. But outlets and marketing were not the only areas where JCB’s strategy resembled the carmaker’s. First, it expanded its capacity by investing Rs. 750 crore. While the plant in Ballabgarh was rebuilt, a new unit was set up in Pune to make heavier machines like excavators. To support the expanded operations, the company was restructured in 2008 and separate business heads were created for Ballabgarh and Pune.

To make these machines and their spare parts cheaper for the price-sensitive Indian customer, JCB localised its products. More than 80 percent of the parts used in a backhoe loader are sourced locally. This includes the indigenous engine that the company brought out earlier this year. It helps that technical know-how comes from the parent company in the UK, which is also famous for making the world’s fastest diesel car. “For two years, we worked with our vendors before launching the engine for machines made here in India. So when we launched, it was simultaneously done in each and every market of ours, no matter how interior,” says Sondhi, who earlier worked in Honda Power Equipment and Tata Steel.

There are plans to make JCB India a hub for serving markets in Africa, Middle East and South East Asia. The Pune facility also includes a fabrication unit, and half of its output is exported back to the parent company in the UK. “We have already started exporting machines from Pune,” says Sondhi.

Future perfect?

The international trend in the construction machine space has seen users making the transition to bigger machines as infrastructure industries mature. In India, players, such as Kolkata-based Tractors India Ltd (TIL), are fast expanding their portfolio. TIL is the distributor for Caterpillar in India’s northern and eastern markets and sells backhoe loaders, excavators and trucks for the American major through its 80-odd outlets. It has also sewn up collaborations with other multinationals like Mitsui and Astec to manufacture or distribute machines like portable plants and tower cranes. “Each infrastructure segment like road or mining has its own specific needs. These requirements will only increase as the mining sector opens up and the government expenditure on infrastructure building goes up,” says Sumit Mazumder, vice chairman and managing director of TIL.

Till now, JCB’s domination is limited to backhoe loaders. Telcon, the joint venture between Tata Motors and Japan’s Hitachi, dominates the excavators segment and Caterpillar is the leader in wheel loaders. (Wheel loaders run on wheels, unlike excavators which run on chains.)

Even though there are many products in JCB’s portfolio that can be brought to India, it has till now kept away from making machines for some key segments like mining. Caterpillar, on the other hand, is the world leader in mining machines and is well placed to take advantage as the sector opens up in India.

But Sondhi scoffs off doubts on JCB maintaining its share. “Every day I think of the competition,” he says, “The trick is to be as close to the customer as possible and listen to his needs.” That again will be through expanding the retail network. He believes that there is a “lot more scope” to expand JCB’s retail network to every district in India. “If we want inclusive growth, infrastructure development has to reach the last village. We want to be present in that process,” Sondhi outlines the vision.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)