Poverty Alleviation in Bihar

Andhra Pradesh and Bihar have shown that a new approach to help the rural poor beat abject poverty works. Now, India wants to try this approach in all states

T Vijay Kumar was standing at a lectern and talking about slaying the dragon of poverty. An Andhra Pradesh Cadre IAS officer, he had fought some stiff battles with the mother of all miseries and so people were keen to listen to him. This was at a conference on human development in Delhi last year. And then he made a statement that caught the policy wonks and social activists by surprise. “No government scheme will have a sustainable impact [on the poor in India] until the poor are organised,” he said. Huh?

Yes, Vijay Kumar’s remark doesn’t quite add up unless you appreciate two things: One, while the human knows how to split the atom, it doesn’t know how to make people ‘un-poor’; two, India has been trying to do exactly this for about 60 years, with poor results.

Indira Gandhi provided India with the slogan of Garibi Hatao (Remove Poverty) in the early 1970s. Since then, most big-ticket government schemes on poverty alleviation have either directly given productive assets to the poor, or provided them subsidies. The hope was that the poor would use them to come out of poverty — by themselves. They did not. Nirmala Devi certainly didn’t.

This 45-year-old woman is an ‘untouchable’ or ‘mahadalit’ belonging to the Ravidas community in Shekhwara village of Gaya district in Bihar. She has three children and both she and her husband are illiterate. Her family income was the 3 kg of poor quality rice that her husband would get as a daily wage for his intermittent work on a farm. To meet the family’s various needs, he would have to barter this rice. Sometimes he would work on some nearby construction site and earn Rs. 80 for a day’s work.

All their efforts at saving money and pulling their family out of penury were mostly undone by some illness in the family. Every illness would force them to borrow from the village moneylender who would charge interest, sometimes upwards of 100 percent. They could not pay back and ended up being under the moneylender’s thumb, providing free labour on his farms. The government had allotted Rs. 2 lakh worth of land but Nirmala had to use it as collateral.

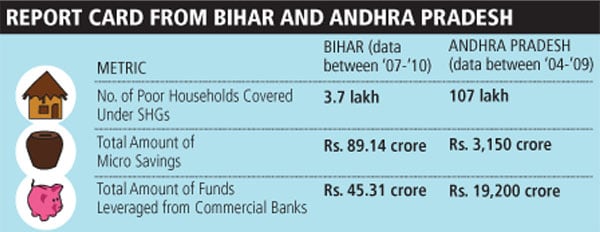

According to Vijay Kumar, you cannot attempt to solve the problem of poverty if you straightaway try and solve it for each individual. That step can be taken only after you have organised the poor into small batches and then target the money at these groups. Vijay Kumar should know. He was the man in charge of implementing such a programme in Andhra Pradesh. Later, the Bihar government used this approach and Kumar’s knowledge to try something similar, called Jeevika, in the state. While in Andhra Pradesh this approach has spread to all districts, in Bihar it covers only nine of the 39 districts at present.

Going National

Now the Central government has asked Kumar to take this approach to solving the poverty puzzle to all states. The new programme is called the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM). At the national level, NRLM would represent a whole new approach to fighting rural poverty in India. The encouraging fact is that the model has had good success in the two states out of the four where it has been tried.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

No one is in a better position to vouch for Kumar’s thesis than Nirmala Devi. Last year, she used the funds from the Jeevika programme to repay her debt and reclaim her land. She then used the funds to start a shop, which eliminated her dependence on agricultural income.

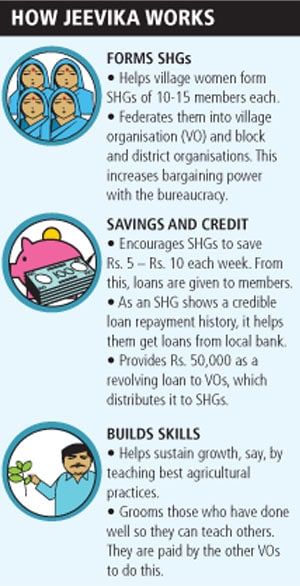

As of now, Jeevika has 370,000 poor households in Bihar within its fold. All the households have been mobilised into 27,317 self-help groups. Each SHG is formed by about 10 to 15 poor women in the village as a mini society that helps its members save small bits of money and use that to tide over tough times by lending among themselves.

So, three months after joining the Suraj Samuh, the name of her SHG, Nirmala needed Rs. 1,000 for her son’s education. This time, instead of asking the moneylender, she took a loan from her SHG at just 24 percent interest and re-paid it over the next eight months.

Nirmala has taken her first steps in the journey out of poverty. This is an interesting approach. The only sure way of removing poverty that economists across the world agree on — as much as economists agree on anything — is economic growth. The industrial revolution made Europeans rich and healthy in about 100 years. It would take another 70 years for countries like Japan and Korea to become richer and healthier — almost at par with Europe and the US. So, India could simply focus on growth and let that lift people out of poverty, say in the next 30 years.

But what do the poor do till economic growth catches up with them in the form of a job or financial support to start a business perhaps?

This is where the NRLM comes in. It organises the poor in a way that they become bankable. Access to formal sources of finance, at half or one-third the cost that they pay to a moneylender, should provide them with a buffer to rework their lives.

Teaching Them How to Fish

A key component of the NRLM approach is to teach women the ways and means to improve productivity from their existing resources. For Nirmala, it was by way of opening a shop but for most others in Bihar it is about increasing agricultural productivity.

Bihar farmers, who have traditionally struggled with land productivity, have adopted the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) for paddy cultivation and System of Wheat Intensification (SWI) for wheat. SRI and SWI require farmers to treat the seeds and sow them at an appropriate distance to get the best yields. Although a far more labour-intensive technique, it results in average productivity gains of 30 percent to 40 percent for the farmers.

But, Jeevika’s indirect impacts are no less credible. Women across different castes have started to come together and work for each other’s prosperity. The dominant identity of women is through their association to a particular SHG and not to a caste.

Moreover, the resulting awareness has meant the delivery of most government schemes has become efficient. For example, in Shekhwara, the village organisation of SHGs went all the way to the divisional commissioner (one for five districts) to get permission to run the public distribution system (PDS) shop in the village since the existing shop owner was corrupt.

The government hopes that what happened in Andhra Pradesh and Bihar will also be effective elsewhere. But the Andhra model was the only one that has succeeded among the original three that were introduced by the World Bank in 2000. Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh failed to stick to the plan and the experiment failed.

Doubting Thomases

This is why not everyone is convinced about the viability of the NRLM framework.

Himanshu, professor of economics at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, feels that this structure undermines the Panchayati Raj institutions since, over time, members of the village organisation (of SHGs) become far more powerful than the Panchayat members.

“It is like bypassing the democratic set-up. At least the sarpanch fights an election every five years,” he says.

Moreover, there are question marks about the veracity of the claims made by World Bank and Society for Elimination of Rural Poverty (SERP) officials. SERP is an autonomous society of the Department of Rural Development, Government of Andhra Pradesh.

“There haven’t been any independent evaluations and none of the secondary data or National Sample Survey figures on poverty, education or livelihood mirror the changes that are claimed,” says Himanshu.

R. Radhakrishna, currently the chairman of the National Statistical Commission and head of the committee that formally suggested moving to NRLM, takes the criticism head on. He accepts that NRLM’s framework is a tacit acceptance that the rural self government systems have not really delivered on their promise. He says that experience has shown that in most states these systems are not very democratic institutions and are largely controlled by the vested interests. The alternative to the Andhra Pradesh or Bihar model is the Kerala model, called Kudumbshree, where since the beginning the SHGs and self government systems were connected and democratic.

“The composition of SHGs [in Andhra Pradesh or Bihar] is more egalitarian, with representation of the women and poor. While the PRIs in these states are dominated by the upper castes and the rich,” he says.

Radhakrishna also refutes the charge that there are no independent studies and refers to two studies, one done by himself and the other by the Centre for Economic and Social Studies.

As an alternative, some have suggested that India should adopt the model that China or even many of the European countries have, wherein each village has a bank, which is run by co-operatives. However, Radhakrishna points out that the Chinese and European societies are far more egalitarian than the Indian.

Nevertheless, while the NRLM approach claims women empowerment as one of its key achievements, women rights activists like Subhalakshmi Nandi of Nirantar are “not exactly happy” about this model being scaled up. According to her, in this approach, women are being “overburdened” with responsibility for their surroundings.

In defence of the programme and its impact on women, Kumar points out that Census 2001 showed just three districts in Andhra Pradesh had a positive sex ratio; in the 2011 Census, it is 11 districts.

The Last Mile Challenges

However, even the proponents of this new strategy are aware that scaling it up at the national level will not be easy.

Srijit Mishra, a professor at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, feels the biggest challenge would be to find enough professionals who would be willing to work at the village level.

Kumar agrees that this is a genuine concern but clarifies that the model focusses on grooming experienced SHG members to train others like them.

“The poor knows how to connect with another poor. The adoption of this model is better primarily because, often enough, the poor are being addressed by someone who they can relate to,” says Kumar.

Radhakrishna says the “institutional architecture” is very important — the political leadership must allow the formation of autonomous societies like Jeevika and SERP.

A big reason why SERP succeeded in Andhra Pradesh and Jeevika in Bihar is that at both places the leadership of the respective societies remained unchanged for almost five years and they were given a free hand. A similar society formed in Orissa has not taken off largely because of the frequent replacement of the official heading the society.

The other big challenge in scaling up stems from the fact that the programme’s focus is on building the capacities of women, who are the most disadvantaged even among the poor.

Experience in both Bihar and Andhra Pradesh has shown that the first few years are tough since there is no easy money being distributed to lure the people to participate.

“It is imperative that the programme is scaled up slowly, giving people the time to realise and understand its benefits,” says Radhakrishna.

“It is for this precise reason that we will attempt to first target only 10 percent of the poorest blocks in the country in the first year,” says Kumar. These would be people like Nirmala Devi. She may never be rich but the society that she lives in now treats her with dignity. “Earlier, people would not even stand next to us. Now they welcome me to their houses,” says Nirmala.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)