Achieving clean energy targets won't be a walk in the park

India has now created an entrepreneurial ecosystem around renewable energy generation. But while government authorities have set lofty targets to explore the potential, will nagging bugbears get the better of them?

On May 8, Germany produced so much electricity around mid-day that its power prices went negative for some time. During that period, its industrial customers were, effectively, paid to consume electricity. The country’s sudden surge in power generation can be attributed to the bright and windy Sunday, when its wind, solar, hydro and biomass facilities generated about 55 GW (1 GW is equal to 1,000 MW) of the 63 GW (about 87 percent) that was being consumed.

While renewable energy’s contribution to Germany’s electricity generation was 33 percent in 2015, the European powerhouse is looking to convert to 100 percent renewable energy by 2050. On some really windy days, Germany’s northern neighbour Denmark generates far more power than its domestic needs and exports the surplus. Even the tiny American nation of Costa Rica spent 75 days of 2015 only on clean, renewable energy.

Where does India, a country whose population is 16 times that of Germany’s, stand in the mix? In theory, right up there. Vineet Mittal, MD of Welspun Energy Ltd, the clean energy arm of the textile-to-steel pipes Welspun Group, says, “In theory, the Thar desert alone has the potential to generate enough renewable energy to feed the entire Saarc [South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation] region [which comprises eight countries representing three percent of the world’s area and 21 percent of its population].”

The strong solar radiation and high velocity winds that this region experiences makes this desert an ideal location for solar and wind energy generators.

But, in reality, it is unlikely that we’ll ever see the 3.2 lakh sq km desert being dotted with wind turbines or solar photovoltaic (PV) panels. At present, renewable energy accounts for around 15 percent of India’s total installed power generation capacity of 288 GW.

This gap gives the country ample scope for capacity addition and makes an attractive destination for foreign energy firms as well as investment funds. In the recent Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index released by EY, India ranks third, after the US and China. “India has the potential to develop close to 900 GW of clean energy from sources including solar, wind, small hydro and biomass and it only needs 2 percent of the country’s wasteland to be made available,” says Mittal.

There has been significant momentum building up for non-conventional power since the NDA government was elected in May 2014. The government set an ambitious target of adding 175 GW of clean energy capacity by 2022. This includes 100 GW of solar power, 60 GW of wind power and 15 MW of biomass energy.

While renewable energy producers, analysts and investors feel that this target might be within reach, they add that it can be achieved only by significantly accelerating the pace of capacity building.

According to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), the total installed renewable power capacity in India stands at 42.75 GW, as of March 31, 2016. In the last fiscal alone, it has added 8,961 MW of clean energy capacity, the highest ever in a single year.

SOLAR TAKES THE LEAD

While the first wave of renewable power in the country was driven by wind energy, solar has taken the lead in the current phase, aided by special emphasis and enabling policies.

Till December 31, 2015, 70 percent of the installed clean energy capacity was of wind energy. The growth was driven by schemes like accelerated depreciation on wind power assets (leading to subsequent tax rebates) and generation-based incentives offered to wind power developers. These benefits were withdrawn in 2012 and led to a slump in the creation of wind power assets before they were reinstated by the NDA government in 2014.

At present there are several factors that are likely to propel the growth of solar power at a pace faster than that of wind energy. First, the government’s target for wind energy (60 GW) is only 60 percent of its aim for solar. Plus, 41 percent of this target has been achieved already, leaving the authorities enough space to make a concerted push for solar power.

Second, the cost of equipment, most notably solar PV cells, has come down drastically compared to the wind turbines. Five years ago, producing 1 MW of solar energy would cost Rs 15 crore; now, it’s only Rs 6 crore, approximately the same as the cost of producing 1 MW of wind power.

Third, the production of wind energy is at its peak during evenings and monsoons, and during both these periods, power demand is low. In comparison, solar power production is more sustained and predictable with most parts of India generally receiving at least eight hours of strong sunlight.

Finally, under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission (JNNSM), launched in 2010, various state governments are making arrangements to offer land to power developers within solar parks as well as ensuring the evacuation of the power produced there through grids. The MNRE has approved the creation of 33 solar parks in 21 states, including Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Odisha and Andhra Pradesh, with a total estimated capacity of 19.9 GW.

POLICY BOOST

The creation of solar parks isn’t the only policy initiative offered by the government to this sector. Other benefits include: Viability gap funding for projects coming up under JNNSM; scaling up of the budget originally allocated under the 12th Five Year Plan for grid-connected rooftop and small solar power plants from Rs 600 crore to Rs 5,000 crore; creation of intra-state power transmission systems in Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Rajasthan at an estimated investment of Rs 8,500 crore; 40 percent of this amount will be provided by the central government from the National Clean Energy Fund.

The government has also taken steps to bring in state-run power producer NTPC to buy clean energy instead of the state electricity distribution companies (discoms). The idea is that if developers get to sign power purchase agreements (PPAs) with a creditworthy company like NTPC, instead of the financially struggling discoms, it becomes easier for them to access debt finance for their projects at attractive rates.

Even independent power producers that began their businesses with wind power installations are re-aligning their operations to take advantage of the government’s emphasis on solar power.

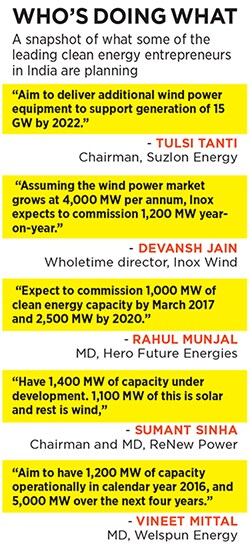

ReNew Power, a five-year-old company founded by Sumant Sinha, is one such example (read: Our Focus is Shifting Dramatically Towards Solar, p50). The company has installed capacities of 880 MW for wind power and 160 MW for solar power. However, of the 1,400 MW it plans to install, 1,100 MW is solar, and 300 MW is wind.

Pune-based Suzlon Energy was once one of the largest wind turbine-makers in the world before it ran into losses. In the midst of a turnaround, the Tulsi Tanti-led company is also getting into the solar space after successfully bidding for a 210 MW-project in Telangana this January.

Even though solar is the flavour of the season, government policies have kept wind power developers happy as well. Devansh Jain, wholetime director at Inox Wind, which makes wind energy equipment, and offers turnkey solutions to the sector, says, “Not only have accelerated depreciation [AD] and generation-based incentive [GBI] been re-introduced but the GBI is actually paid out now, as opposed to it existing mostly on paper earlier. The GBI reforms have led to a huge explosion in the independent power producers’ market for wind energy equipment.”

Companies have also been allowed to claim investments made towards creating renewable energy capacity as a part of their mandatory corporate social responsibility spend (2 percent of net profit) “This has led to a lot of tenders coming in from state and central government undertakings [for wind power equipment],” adds Jain.

INVESTOR RUSH

It isn’t surprising then that investors—foreign power companies, first-time Indian entrepreneurs, traditional conglomerates, and global funding heavyweights—are all willing to take a bet on India’s renewable energy sector.

Take SoftBank Corp, for instance. The Japanese telecom multinational, which has already invested more than $1 billion in India across ecommerce ventures like Housing.com, Grofers, and OYO Rooms is now eyeing the clean energy space as well. In June 2015, SoftBank announced a joint venture with the Sunil Mittal-led Bharti Enterprises and Taiwan’s Foxconn Technology to invest in wind and solar power projects.

“Our eyes are trained on India, given the vast potential that the country offers,” said Masayoshi Son, SoftBank’s chairman and CEO, in a statement while announcing the partnership. “We have already made considerable investments in the technology sector here. With this partnership, our goal is to create a market-leading clean energy company, to fuel India’s growth with clean and renewable sources of energy.”

Last October, the Aditya Birla Group announced a similar partnership to develop solar power assets in India with Dubai-based The Abraaj Group, a private equity investor focussed on emerging markets, including Asia, Africa, Latin America, Middle East and Turkey.

India is currently the fourth largest renewable energy market in the world in terms of investments. According to Bloomberg, the country had investments to the tune of $8.86 billion in 2015.

While investors like SoftBank are looking at the Indian alternative energy space only now, those who have invested in the sector over the years are reasonably happy with their experience.

International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group, has been investing in the equity of Indian renewable energy developers since 2007 and, as of March 2016, its cumulative investments in the sector, including mobilisation of funds from other investors, was more than $750 million, a quarter of its infrastructure portfolio in the country. IFC’s investments have helped create 3,000 MW of clean energy capacity in India, says Gaetan Tiberghien, the power sector lead for South Asia at IFC.

Traditional Indian conglomerates are also looking at renewable energy as a new avenue of growth, much like they looked at telecom as a sunrise sector at the beginning of the last decade.

The $5-billion Hero Group, promoted by the Munjal family, is one such business entity. In 2012, it promoted a new company, Hero Future Energies, which has an installed renewable power capacity of 360 MW, and plans to install another 1,000 MW by March 2017.

“Businesses are realising that renewable energy has potential. Earlier, people had apprehensions that clean energy was expensive and whether buyers would find it valuable,” explains Rahul Munjal, MD of Hero Future Energies. “But people have now accepted that renewable power is here to stay and the government has done a wonderful job of selling this sector to investors.”

Munjal also adds that, from an execution point of view, renewable power is a very “clean business” for a conglomerate to get into: “It is fairly upfront and government interactions are transparent.”

TARIFF’S A RED FLAG

So far, growth of the clean energy sector in India has been fairly smooth. But experts point to a number of bugbears that can derail the story. Tariffs remain the biggest concern, particularly for solar energy, because the house remains divided on what should be the optimum figure, and because that can potentially wane its value to the investors.

A section of power developers, lenders and analysts believe that, to be financially viable, solar power projects need to command a tariff between Rs 4.80 and Rs 5 per kilowatt hour (kWh). They feel that companies bidding lower than this threshold are doing so to aggressively corner projects, and that the situation is a repeat of what happened in the thermal power and roads sectors where companies bid low tariffs and toll collection numbers, without appropriately factoring in the costs and risks associated with developing these projects. As a result, many of these projects were rendered unviable and abandoned.

Raj Prabhu, CEO and co-founder of Mercom Capital Group, a solar energy consulting firm, points out that many of the low bids that are being put in by companies to win projects at present are based on the assumption that, in six to 12 months, when these projects become commercial, costs would have dropped low enough to justify the tariffs.

“This is risky execution. All it takes is for one or two projects to go wrong and we might see a repeat of what happened in the infrastructure sector in the past,” Prabhu says. “The government has to keep a close watch and ensure the viability of projects that are being awarded.”

Similar sentiments are echoed by Mittal of Welspun Energy. “Some people are over-optimistic and our biggest fear is that some of the capacity that companies are executing may not materialise. Profitability may become an issue for some and the sector may go through a major restructuring in years to come,” he says.

Of late, there have been instances of companies having secured government projects, through competitive bidding, by quoting tariffs lower than this benchmark. For instance, SunEdison, the largest global renewable energy development company that filed for bankruptcy in the US in April, had won a solar power project in Andhra Pradesh in November 2015 by quoting a tariff as low as Rs 4.63 per unit.

Again, this January, Finnish company Fortum Finnsurya Energy bid an all-time low of Rs 4.34 per unit to win a 70 MW-project in Rajasthan. These companies believe that the removal of risks associated with developing alternate energy projects (like land acquisition) and plummeting input costs can justify low tariffs.

In an interview with Forbes India in February, before the company filed for bankruptcy, Pashupathy Gopalan, president, SunEdison Asia Pacific, had said that not just SunEdison, but at least 10 other large independent power producers in India had quoted tariffs lower than Rs 5 per unit. “The prices of solar PV modules are coming down by 10 to 12 percent per year, the yuan has depreciated versus the dollar [which helps India as an importer of Chinese solar power equipment], and risks associated with development have been eliminated by the government,” Gopalan had said.

He had added that with the elimination of development risks, investors are willing to settle for an adjusted return on investment (RoI), lower by as much as 100 basis points (bps). Similarly, when a creditworthy entity like NTPC steps in and agrees to buy power from a project, lenders are willing to reduce the cost of capital by 50 to 75 bps.

While the financial trouble at SunEdison had been brewing for a while and hasn’t been directly linked to the low tariffs it quoted for its Indian projects, its downfall could adversely impact even promising markets like India.

IFC’s Tiberghien partially agrees with Gopalan’s logic, albeit with a rider. “Tariff reductions are good for the sector and additional reductions are desirable as long as they are sustainable. A good risk-return balance needs to be maintained to attract the huge capital needed to achieve India’s targets. If this balance is not adequate, fewer investors will bid, awarded projects won’t get built and/or project quality could suffer.”

THREAT TO INVESTORS?

Besides abandoned projects, lower tariffs are also bound to bring down the internal rate of return (IRR) and make the sector less attractive for investors.

Jayesh Desai, co-head of Structured Investments Group at Piramal Enterprises Ltd, which provides structured mezzanine funding (a hybrid of debt and equity) to companies, says that with tariffs of Rs 4.30 to Rs 4.60, an investor can make an IRR of 12 to 13 percent on a solar power project, which isn’t sufficient given the risks associated with a project.

“Anything below a 15 percent return is in marginal territory and will make it difficult for developers to raise equity funding from investors. You cannot have a situation where the cost of debt is 11 percent and equity with all its attendant risk yields a return of only 12 percent,” Desai says.

He adds that RoI in clean energy is super sensitive to miscalculations in operational efficiency. The average capacity utilisation level assumed for any clean energy project is 18 to 20 percent (since the sun doesn’t always shine, nor does the wind blow throughout the day). If the utilisation rate goes wrong by even 1 to 2 percent, it can shave off 5 to 6 percentage points from an investor’s IRR.

But the power minister is determined to make low solar power tariffs viable by bringing down the cost of equipment further. Speaking at the Make in India Week exposition in Mumbai in February, Piyush Goyal had said that, within the next 18 months, his ministry’s ambition was to transform India into a manufacturing hub for solar power equipment, which would be cheaper than those available anywhere else in the world.

TROUBLE WITH DISCOMS

Prabhu of Mercom also points out that peer pressure among state discoms has resulted in plummeting solar power tariffs in the country. If the tariff for solar power in one state touches a low of Rs 4.50, other states also demand a similarly low tariff without taking into consideration specific issues. For instance, a company looking to set up a solar project in Rajasthan may quote a tariff of Rs 4.50, keeping in mind the high solar intensity in the state. But the tariff in, say, Karnataka may be higher because solar radiation is weaker in the state than Rajasthan.

Besides, the poor financial health of state discoms and the slow pace of reforms in transmission and distribution stand to hurt the renewable energy sector. Mounting debt and losses have led some state discoms, like Tamil Nadu’s, to delay payments to companies. It has also deterred them from signing new PPAs. The industry is hoping that Goyal’s pet project, christened UDAY (Ujwal Discom Assurance Yojana), will help in this regard.

Through UDAY, a voluntary scheme, the central government is allowing state governments to take over 75 percent of the debt from the discoms and repay lenders by selling bonds. Discoms have been allowed to issue bonds directly for the remaining 25 percent. In exchange, they have to commit to a certain level of operational improvement.

“This will improve the health of the discoms considerably. With more funding available to them, they will be prompt in making payments and have a better credit rating,” says Tulsi Tanti of Suzlon. “Not only does this open up funds for investment in renewable energy, it will also help discoms meet their minimum renewable power purchase obligation.”

Finally, even though it wants to add 175 GW of alternate energy capacity by 2022, the government should look into whether India’s national power grid has the wherewithal to absorb the rise in power generation. “Even developed countries like Germany and China have had to curtail power production when their installations hit a generation of 7 GW and 10 GW in a year, respectively,” says Prabhu. “And none of these countries have the level of transmission and distribution losses that India has [around 23 percent].”

Will it cast a shadow on India’s new sunshine sector? Only time will tell.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)