Big story: Making it work for women

More rural women than men have lost their jobs due to the pandemic, and they could be the key to building a stronger economic revival

Chanda Devi does farming, animal husbandry and runs her family’s box-sized kirana shop in Majhaulia village in the Muzaffarpur district of Bihar

Chanda Devi does farming, animal husbandry and runs her family’s box-sized kirana shop in Majhaulia village in the Muzaffarpur district of BiharChanda Devi speaks with a smile. One that belies the tension about her 1 acre farm in Majhaulia village of Bihar’s Muzaffarpur district being ravaged by floods. Income has almost halved because she had to sell the eggplants, potatoes and okra she grew at lower rates during the lockdown. Then there is the monthly instalment of ₹2,000 toward repaying a ₹50,000 loan she had taken from her self-help group (SHG) to set up a box-sized kirana shop. “Kahin na kahin se toh minus karna padega,” says the 30-year-old. She will have to cut some other expenses to ensure she does not default on her instalment.

Devi is determined to not let these challenges get to her. She had started working in agriculture as an 18-year-old newly married woman who needed to push her family out of penury. She joined an SHG in 2012 to take a loan of ₹20,000 and get back their farm that was mortgaged with the local money lender.

“My husband is not really a self-starter. He is better at doing something he is asked to do,” says Devi, who wakes up at the crack of dawn, feeds the cows, sweeps and mops her home, cooks for the family, works in the field for over 6 hours, attends meetings at the SHG and the Farmers’ Producer Company (FPC) she is part of, returns home to cook, wash clothes and take care of her elderly mother-in-law.

She finishes all the domestic chores alone, without any help from her two sons, her brother-in-law or her husband, the latter only helping her in the farm. “I started working only because I had no other option to get my family out of financial difficulty. But I have always wanted to be independent,” she says. “Times have been tough again, and I know that my work and my income are essential to keep my family afloat.”

A 2018 Harvard Business Review report states that globally, for every 10 percent increase in women working, there is a 5 percent increase in wages, including for men, since the overall productivity levels of the regions with better female labour force participation (FLFP) increase.

Kumaribai Jamakatan (extreme right) has taken it upon herself to help the tribal women of her community in the Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra

Kumaribai Jamakatan (extreme right) has taken it upon herself to help the tribal women of her community in the Gadchiroli district of MaharashtraThe International Labour Organization (ILO), in global policy guidance notes for its Decent Work Agenda to empower rural women in 2019, said that productive employment and good quality jobs for women in rural areas “not only contributes to inclusive and sustainable economic growth, but also enhances the effectiveness of poverty reduction and food security initiatives, as well as climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts.”

Yet, in India, when the economy slows down and jobs start disappearing, women’s livelihoods have often been the first to be hit. The 2020 World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap report ranks India at 149 out of 153 countries when it comes to economic participation and opportunity for women. According to the report, only 35 percent of the financial gap between women and men has been covered.

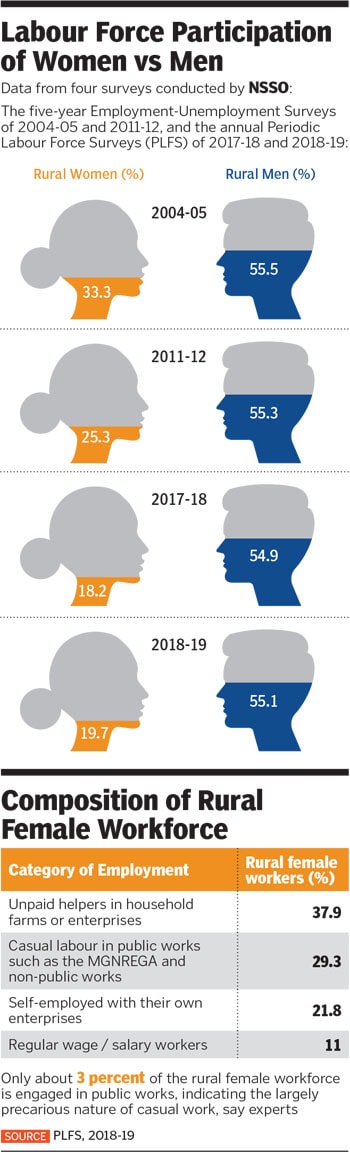

Rural women particularly fall out of the workforce at a much sharper rate than urban women. Data from the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) indicates that FLFP in rural areas fell from 33.3 percent in 2004-05 to 19.7 percent in 2018-19. This is a sharper fall compared to rural men, who’s participation fell from 55.5 percent to 55.1 percent in the same period, or urban women, whose participation fell from 17.8 percent to 16.1 percent.

Jayashree is among 25 women who found a livelihood in an apparel unit established by the state government in the Kollam district of Kerala

Jayashree is among 25 women who found a livelihood in an apparel unit established by the state government in the Kollam district of KeralaImage: R Ravi

A survey of 5,000 workers across 12 states conducted by the Azim Premji University (APU) between April and May found that 71 percent rural women casual workers lost their livelihoods during the lockdown, compared to 59 percent of men. The proportion stood at 45 percent each for self-employed men and women in rural areas.

The Covid-19 pandemic is likely to exacerbate issues, so much so that the slight uptick seen in the FLFP for the first time in over a decade, from 18.2 in 2017-18 to 19.7 in 2018-19, might not sustain and is not considered a significant enough gain by experts compared to the rate at which labour participation has fallen over the years.

She also points out that women were the de-facto head of the family and in-charge of farmlands when the men of the house migrated to cities for work, but since the latter have come back to the villages, they will have to be absorbed in agriculture and non-farm jobs. States do not have gender disaggregated data for the returning migrants. “So a lot depends on what happens to job opportunities for men. It is in that context that we have to view what happens with the female labour force and opportunities for them, and not in isolation,” Gulati explains.

That said, workforce participation of rural women has primarily been driven by need. The sudden income shock created by the pandemic could also lead to reengaging women in the economy because distressed households are looking at ways to increase income levels, believes Rosa Abraham, research fellow at the Centre for Sustainable Employment at APU. “It is practical to have a gendered lens to policy-making right now, because people are desperate for work. Policy that provides for work will find takers in the economy, and a lot of these takers are going to be women,” she says.

Economists believe that a gendered approach would involve a set of holistic measures, ranging from pay parity to more formal recognition of work done by women.

Education-Employment Trade-Off

There is a U-shaped pattern between increasing numbers of rural women getting access to education and still not joining the paid workforce. Mehta of IWWAGE explains that the majority of women are unpaid workers who assist with household enterprises or agricultural work, and the ones in non-public casual work are often engaged in precarious or vulnerable jobs. The women who get educated seek careers outside of these sectors, but are constrained by the lack of availability of jobs that would be commensurate to their education.

“Rural women also want part-time jobs so that they are able to accommodate their household chores. Those kinds of roles are not available across geographies at the district level. So women end up taking odd jobs in the informal sector, because flexible options in the formal sector are just not created in rural India,” she says.

While women are usually restricted from migrating to nearby towns and cities to access skill training and jobs, the government can create support infrastructure to help them access these opportunities, adds Kanika Kingra, senior policy and advocacy manager at IWWAGE. “This would include hostels for girls, tackling issues around mobility and safety, creating creches and child care centres,” she says.

Gulati points out that even as the majority of rural women are engaged in agriculture, they often do not get access to credit facilities, subsidies or even agricultural tools because of lack of asset ownership. “Most of the land is registered in the name of male farmers,” she says. According to an Indiaspend report in 2019, only 13 percent of women own the land they till.

The government, on its part, is banking heavily on organising women into SHGs to empower them. “Community-building is essential to helping women get the confidence to step out of their homes and work. The National Rural Livelihoods Mission [NRLM] has mobilised about 6.8 crore women with a capitalisation support of ₹10,200 crore so far,” says Alka Upadhyay, additional secretary, Union Ministry of Rural Development.

Cultivating community leaders would also help the government reach the most marginalised people effectively, believes Nikita Wadhwa, programme coordinator for Collective Impact Partnership, an initiative that supports local women who undertake leadership roles by helping others in their community. “They work closely with decision makers to ensure that women can access government schemes and policies meant to empower them, and work to address systemic barriers and gaps,” she says.

Women who run their own enterprises in villages barely earn half the revenue as their male counterparts, Mehta of IWWAGE says. “She does not make enough because she does not have networks to connect to markets or access information on products, training etc,” she says. “There needs to be marketability around what these MSMEs are creating. Governments can be encouraged to make a certain proportion of their procurement through women-led enterprises.”

Abraham of APU agrees that government support to decentralised community institutions can empower women socially and economically. “Kerala, for example, provides extensive credit to women-led businesses under Kudumbashree [community organisation of neighbourhood groups]. Other states could look at creating similar channels to provide more funding and resources to rural women entrepreneurs,” she says. In its 2020-21 budgetary outlay, Kerala earmarked ₹1,509 crore for women-related programmes. This was 7.3 percent of the overall budget, an increase from 4 percent the previous year.

It is under Kudumbashree that Jayashree (who uses only her first name) found a livelihood with a steady income, along with 25 other women, at an apparel park established with the help of the Nedumpana gram panchayat in the Kollam district of Kerala. Initially, they ran into losses to the tune of ₹3.5 lakh because of low margins, difficulty in marketing their products and delays in payments. Then, three years ago, the government supported them with procurement orders for stitching uniforms for the Kochi Metro and the state lotteries department, apart from orders from state hospitals. “The government orders helped each of us get a stable income of up to ₹15,000 per month,” she says.

During Covid-19, the women set up sewing machines at home and stitched over 1 lakh masks each for gram panchayats and government departments, and another 1 lakh for the Karunya Community Pharmacy, the state-run retail chain that provides medicines at affordable prices. Jayashree explains that the women are paid per unit of clothing they stitch, and each of them was able to earn at least ₹30,000 through these Covid-19-related orders. “We never say no to any job order that comes our way. Even if we cannot do it ourselves, we pass it on to the smaller women-run stitching units so that they also earn a livelihood,” she says. “Women must help each other.”

Playing to the Strengths

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), the government’s flagship rural jobs programme that provides 100 days of work per household with minimum wages, has allayed the job distress for many migrant workers. Experts suggest that job cards can be provided to more women under this scheme so that they do not lose out on work in a competitive labour market that now includes returning migrants.

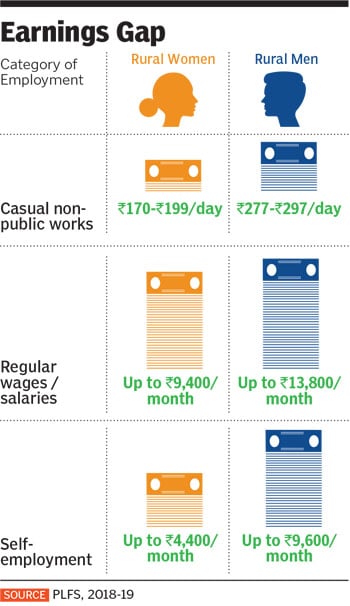

Abraham of APU says that lessons from MGNREGA can be applied to other sectors predominantly employing rural women, including the health sector. For one, the jobs programme has equal wages for men and women. Otherwise, the wage disparity between men and women in rural areas is steep, where women’s incomes could be as low as half as that of men.

“The MGNREGA has also streamlined payments through post office and bank accounts, although there are still delays in compensation,” Abraham says. “Some of these best practices could be adopted with respect to anganwadi and Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), where the money often does not trickle down to the grassroots.”

Chinmayee Barik, a nurse with the medical mobile unit of the Tata Steel Rural Development Society in Jajpur district of Odisha, says ASHAs have been at the frontline of collecting data on Covid-19 response and tracking migrants, which is then processed by her team. “Their responsibilities have increased two-fold, and they are at a health risk, but are paid a meagre ₹6,000 per month. They need to be compensated properly,” she says.

Kingra of IWWAGE says the government must refocus on its strengths in the care economy and formalise the employment of the millions of ASHA and anganwadi workers. “In the Covid-19 context, the demand for such workers has increased. They should be recognised as part of the formal workforce with competitive wages and incentives like health insurance.”

Abraham suggests that the government could invest in social security in the form of universal basic services in the health and education sectors, which employ a lot of rural women. This, she says, will have “multiplier effects in the economy, whether it is building up health or school infrastructure. So these sectors could absorb more women”.

She also points out that it is important to understand a typical woman’s work day and the metrics of measurement should not overlook the different forms of care work. “If we have to assess women’s participation in the economy, domestic work could be statistically taken into consideration.”

● With inputs from Namrata Sahoo

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)