Covid-19: International migrants take long road home

The return of international migrant workers due to the pandemic is likely to intensify in the coming months, creating additional challenges for India, which is already struggling to help its domestic migrants

Indians wait at the Dubai International Airport for a flight back home in May. The Gulf countries have some of the highest numbers of workers from India, many of who now face an uncertain future as industries shed jobs and governments give preference to local employees

Indians wait at the Dubai International Airport for a flight back home in May. The Gulf countries have some of the highest numbers of workers from India, many of who now face an uncertain future as industries shed jobs and governments give preference to local employeesImage: Karim Sahib / AFP Via Getty Images

Martin Xavier describes himself as a “true migrant”. His career trajectory over the last 25 years as an engineer in the oil and gas (O&G) industry has involved moving from one country to another. The 47-year-old spent the last decade working in Kazakhstan, before which he was employed in the Middle East. His international migrant worker status received a sudden jolt in March, when he came back home to Mumbai for a family emergency and was unable to return to his place of work. International flights were suspended indefinitely due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and, in April, his company informed him that he had been laid off.

Some of his fellow Indian colleagues met with a similar fate. “I have no clarity about my future. We don’t know when the airports will open up. Even if they do, the O&G industry has been hit because of low crude prices, so we have no idea if companies, both abroad and in India, will have jobs to give. It’s a double whammy,” says Xavier.

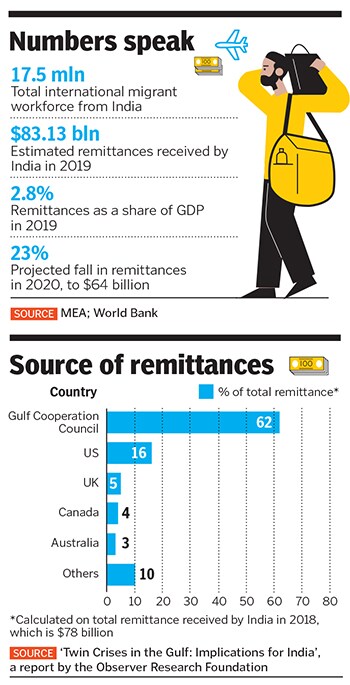

One in 20 migrant workers worldwide is Indian, according to the World Economic Forum. India has been among the top origin countries of international migrant labourers since the United Nations (UN) started tracking the roots of these workers in the 1990s. The movement of people, both within and outside the country, soared with the 1991 economic reforms that stressed on globalisation and liberalisation. The ‘Global Migration Report 2020’ brought out by The International Organisation for Migration, a UN agency, says India has the largest number of migrant labourers living abroad, at 17.5 million, followed by Mexico at 11.8 million and China at 10.7 million.

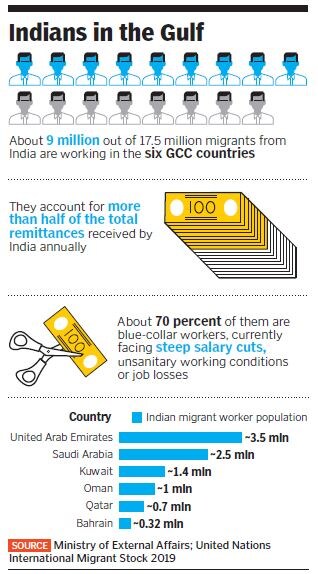

According to the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), about 50 percent of this 17.5 million migrants—around 9 million people—are in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The UN estimates that about 70 percent of these are blue-collar workers, and only 30 percent are skilled professionals.

While it took a pandemic for India to wake up to the humanitarian crisis faced by its internal migrant workers due to decades of social, political and financial exclusion, experts point to another migration crisis in the offing. “Countries world over have started talking about visa restrictions and are shutting their borders to ‘outsiders’. Every nation wants employment opportunities to go first to locals, given the global economic crisis,” says Irudaya Rajan, a migration expert with the Centre for Development Studies (CDS) in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. “At least 10 to 15 percent of India’s total international migrant workforce is expected to return in the next six months.”

An example of how countries are trying to reduce the dependence on foreign workers is a draft expat quota bill approved by the National Assembly of Kuwait in July, which states that Indians should not exceed 15 percent of the national population. Kuwait’s population is 4.3 million, of which about 1.45 million are Indians. Implementing this piece of legislation would mean that about 800,000 Indians would be forced to leave the country and return to India.

Labourers in the O&G, construction and hospitality industries will be the most-affected, and it will be a challenge for the Indian government to create jobs according to the specialised skill sets acquired by these workers over the years, says Shyam Parande of the India Centre for Migration, an autonomous think-tank of the MEA that conducts research on international migration patterns of Indians in order to inform policy-making. “India is looking at at least 2 million people coming back,” he says, seconding Rajan’s estimates.

While the size of international migrants is not too large compared to India’s total population, the money the country receives from them in the form of remittances is not a small amount. According to the MEA Annual Report, Indians living abroad sent a total of $78.6 billion dollars in remittances to India in 2018. A World Bank report estimates that while this amount may have reached about $83 billion dollars in 2019, it is likely to reduce by about 23 percent in 2020, the sharpest decline in recent history. The Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in fall in wages and loss of employment in host countries, which will result in the annual remittances received by India falling to about $64 billion, the report said.

Double-Edged Sword

“Migration, be it inter-state or international, still does not have recognition as a factor that needs to be integrated into development planning,” says Ram B Bhagat, professor and head, department of migration and urban studies, at the International Institution of Population Studies. “If people are going to lose jobs and come back all of a sudden, then sensitisation is required at various levels in the central and state governments to handle this.”

According to him, the impact of international migrants coming back home will be two-fold: “One will be at the household-level, where low or lack of income will affect education of children and heath care of the elderly. Second, a reduction in remittances will affect the capacity of states to perform.”

Xavier agrees that the government needs to be more sensitive about the challenges faced by workers. He believes that he would have been in a better position to plan his next steps if the Indian government had given any prior indication of a nationwide lockdown being imposed. Approaching the issue with empathy and understanding of ground realities faced by workers is necessary to help them deal with the uncertainty, he says. “But their approach shows an absolute lack of common sense.”

Rajan of CDS says the pandemic has exposed the discriminatory treatment meted out to both internal and international migrants. He believes that the latter can be categorised into three groups so that the government can devise policies accordingly. “About a third of international migrants are ‘normal returnees’ who had always planned to return, so they have a plan and savings. The problem now, is that the government will have to create opportunities for them to invest here,” he explains.

“The second group of people, around 30 percent, are re-migrants. These people will surely move out of the country again at the first given opportunity and re-employment is very high among them. For example, health care professionals.” The remaining, according to Rajan, are distressed international migrants, who are the most vulnerable.

He explains that this group of people, particularly in the Gulf countries, often live in overcrowded camps in less-than-sanitary conditions; many have been stripped off their livelihoods due to the pandemic and have no savings, not even enough to travel back to India from wherever they are. “These people need rehabilitation programmes that every state must put together along with the Centre,” he says.

Even skilled and semi-skilled workers have their own share of challenges of working in Gulf countries, which accounts for more than 50 percent of the total remittances received annually by India. Karthika Santhosh, a digital marketer in the health care industry from Kottayam, Kerala, has been staying in the UAE for seven years now, but has never felt so uncertain about her future there.

The 32-year-old is holding on to her job despite a 30 percent salary cut because she has a loan to pay off, but says there is “no job security in the long term”. She explains, “The new law permits employers to ask us [non-local residents] to go on unpaid leave for long periods or even sack us,” she says. Free Covid-19 tests are only for citizens, pregnant women and residents over 50 years. “Now, I realise how much being considered a citizen of a country matters.”

Opportunity in Adversity

Parande says the MEA and individual embassies have been constantly getting calls and queries from migrants abroad. He does not share exact numbers, but says “returnees first want to know how they can come back at the earliest, and are then expecting the government to support them with employment when they do.” He believes that the government should start collaborating with reliable recruitment agencies, which, according to his estimates, send almost 2 million labourers to other countries in a regular year.

“Government will have to orient recruitment agencies with incentives so that they can help returnees with the required livelihood assistance. They can also together figure out which countries people can be sent to for pursuing new employment opportunities,” says Parande, who is also the secretary of Sewa International, an NGO that partners with the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh in a few countries.

There is a regional lopsidedness to the distribution of international migrant workers, and that states must frame policies accordingly, says Bhagat. “For example, about 30 percent of Kerala’s revenue comes from international migrants, most of them settled in the Gulf. So the state has an institutional framework in the form of a Department of Non-Resident Keralite Affairs and politically active associations for returning migrants to address their issues. States like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, on the other hand, have a high domestic migrant population and have international migrants only in a few pockets.”

Rajan, who is working with the Kerala government on international migration, estimates that at least 300,000 people will return this year, the highest for any state in India. Covid-19 could create new job opportunities in sectors that had not been imagined earlier, especially in health care and sanitation, but the government must help migrant workers reskill, upskill or get access to technology training to suit the changing realities of the economy, he says. “We can relook at the provisions of the Skill India programme to focus on this.”

Regular data inclusion of international and inter-state migrants is essential for implementing targeted policy frameworks, says Bhagat. The government has often adopted a narrow view when it comes to international labourers, often getting caught up with the ‘diaspora’, or focusing only on those they think will invest in India, he says. “So we have big events like the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas for them. But it’s time the government does not sideline the temporary or distressed migrants, who are the real heroes.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)