Cyber threat: Enemy at the gates

The digital revolution may have made life easier for citizens, but it has also thrown up new challenges for organisations. Despite spending billions, are Indian companies geared up to battle this cyberwar?

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

No cyber threat, however over-the-top its depiction, seems far-fetched today. Take the 2017 instalment of the movie franchise The Fast and the Furious, in which cars hacked into by an antagonist, who was sitting in a plane 30,000 feet up in the sky, drop off a multi-storey parking lot in New York—by themselves. Far from gimmicky, the high-octane scene, in fact, strikes a chord, reflecting the grave danger that a digitally connected world faces.

After all, real life isn’t bereft of such drama either as Indian companies —much like their global peers—have found out. On the rain-soaked morning of July 21, 2016, Arun Tiwari, former chairman and managing director of the state-run Union Bank of India (he retired in June this year), found himself in office, not knowing whether the $171 million (a little over Rs 1,100 crore) just stolen from his bank by hackers would ever be recovered. The said sum had been debited from one of Union Bank’s foreign accounts and had made its way to multiple other accounts across the world, using SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication), a mechanism employed by global banks to transfer funds electronically.

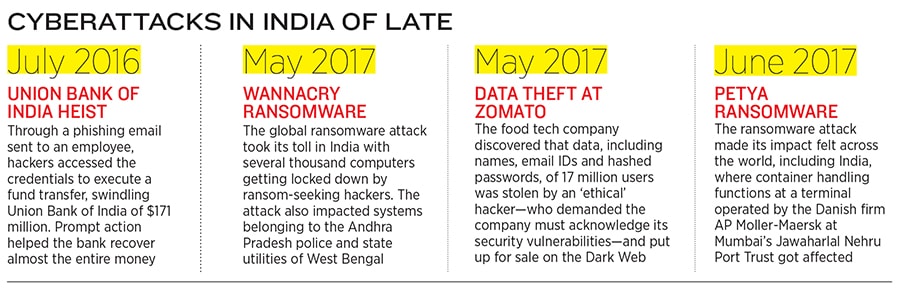

Investigation later revealed that one of Union Bank’s employees had fallen prey to a phishing email, masked as sent from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which infected the bank’s network and gave the hackers access to the credentials needed to execute the transaction. However, Tiwari kept his nerve and initiated swift action, which included hiring Ernst & Young (EY) to investigate the fraud, and ensured that his bank’s loss was limited to a mere $497 (Rs 32,000).

The importance of timely action in recovering losses arising out of such a breach is evident from the fact that a similar e-heist of $101 million faced by Bangladesh Bank in February 2016 led to a loss of around $63 million by the time the bank realised and responded to the attack.

No, the drama is real.

And it is the result of progress. The irony is not lost on anyone, particularly technopreneurs and experts who know just how large the threat is. Mark Anderson, president of Palo Alto Networks, a $1.4-billion network and enterprise security company based out of Silicon Valley, points out that over the years, the cost of carrying out a successful cyberattack has dropped to almost nothing. “You can buy a cheap computer and copy a code script made available on the dark web by other criminals,” Anderson told reporters recently. “Consequently, the number of successful attacks has risen dramatically.”

Perpetrators of cyberattacks range from state actors to individual thieves looking for money or data that can be monetised, and even hackers out to merely prove a point. Take for instance Russia, which is alleged to have interfered in the 2016 US presidential elections that brought Donald Trump to power; or North Korea, which was reported to have hacked Sony Pictures Entertainment, miffed with the depiction of its supreme leader Kim Jong-un in a film (The Interview) produced by them.

Closer home, increasing online retail, the government’s efforts to create a cashless economy (especially post demonetisation), and the growing number of computer and smartphone users in a country of over 1.2 billion people are making India a more connected nation. That automatically also makes it more vulnerable to cyber threats.

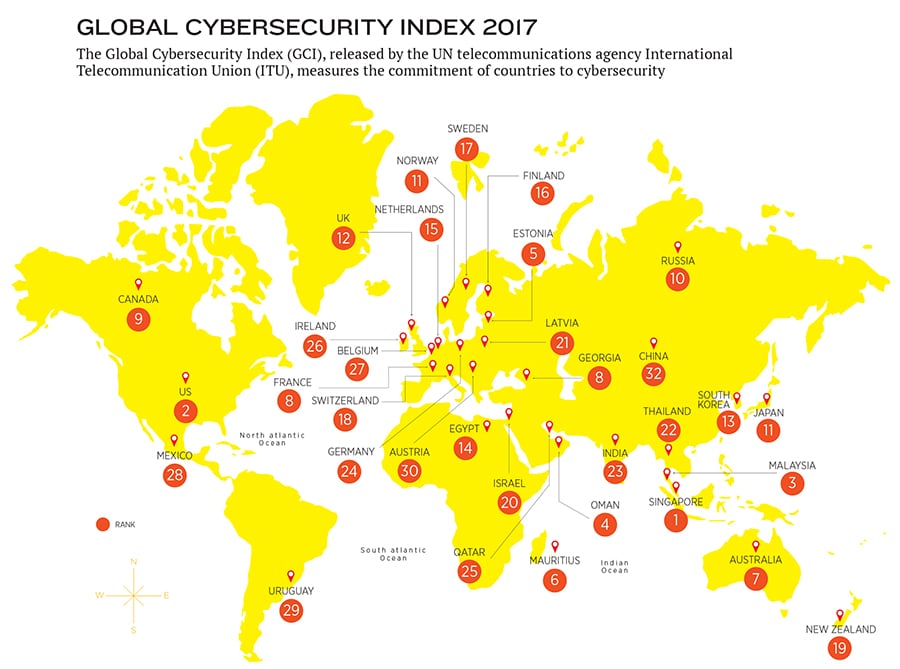

But here’s the good news: According to the 2017 edition of the Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI) released by the United Nations International Telecommunications Union, India ranks 23rd out of 193 countries in the world. The GCI puts India in the bracket of ‘Maturing’ countries that have “developed complex commitments, and engage in cybersecurity programmes and initiatives,” according to the report.

That the country ranks ahead of superpowers like Germany is a positive for its digital fortress, but the strength is relative. The fact remains that many devices in India are afflicted with malware. Another report by SophosLabs, a cybersecurity products and services company, says that India is fifth-most prone to cyberattacks due to malware, after Algeria, Bolivia, Pakistan and China.

In May, organisations across the world, including India, were wary of a ransomware attack christened WannaCry that hit computers belonging to, among others, the Andhra Pradesh police and some state utilities in West Bengal. This was followed by a similar attack called Petya in June, which impacted operations at a terminal at the Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust in Mumbai, operated by AP Moller Maersk.

It is easy to see why cybersecurity is no longer the sole purview of a company’s IT team, but part of the board-level agenda. In the India cut of KPMG’s Global CEO Outlook 2017, which surveyed 131 Indian CEOs, 53 percent of the respondents agreed that their organisations weren’t fully prepared for a “cyber event”, and an overwhelming 89 percent were comfortable with the degree to which mitigating cyber risks was now part of their leadership role.

“Cyber security is a concern all over the world and we take it very seriously as well,” Adi Godrej, chairman of the Godrej Group, tells Forbes India. “The advantage of ensuring a robust cybersecurity policy is that it keeps cybercriminals at bay from even trying to attack your system, because there is time and effort in doing so involved at their end as well.”

Clearly, cybersecurity is no longer a choice. “It is a must for every company to ensure business continuity, information confidentiality, integrity and availability in the increasingly digital ecosystem,” says Vimal Kejriwal, CEO and managing director of KEC International, the engineering arm of RPG Enterprises. Kejriwal says KEC is currently executing projects across 37 countries, and digital technologies are relied on considerably to exchange information between sites. “We are participating in more and more reverse auction as we bid for projects. We are also leveraging e-procurement in dealing with our suppliers. Maintaining the confidentiality and integrity of information is extremely crucial to maintain competitive advantage,” he says, adding that his company has doubled its budgetary allocation towards cybersecurity measures.

Godrej points out that his group has been focussed on having strong cybersecurity policies even before the recent spate of attacks made news. “Just like we protect our physical assets like factories, we ensure the security of our digital systems,” says Godrej.

However, maintaining multiple databases (essentially splitting and storing user information across various places instead of one location) helped Zomato minimise the damage. It prevented sensitive data such as users’ financial information from being leaked. “We were lucky we could get in touch with the person (hacker) in good time. As it turned out, the hacker was a security researcher (ethical hacker) who had put up the data for sale to get our attention (and/or to teach us a lesson),” Zomato’s founder and CEO Deepinder Goyal wrote in a blogpost dated May 23. “He/she only wanted us to launch a good bug bounty programme on HackerOne (a platform that connects businesses with ethical hackers), as he/she wanted to make sure that security researchers were rewarded well for their work.” After Zomato accepted the hacker’s conditions, the database was taken off the dark web and the hacker agreed to destroy it, according to the company. “This incident taught us a good lesson on the importance of security and how we have to be paranoid about it going forward,” Goyal wrote in his blog post.

The aviation industry is particularly sensitive to digital miscreants. Neelu Khatri, the India president of Honeywell Aerospace—a manufacturer of aviation components—says as airplanes evolve from being purely mechanical to a “highly interconnected cyber-physical system”, the transformation creates more opportunities for cybersecurity attacks. “All flight systems are built with redundant backups and, most importantly, the flight crew always has control of the airplane and the ability to override flight systems,” says Khatri.

While CEOs need to be “paranoid” about digital security, the onus of protecting the organisation lies with the chief information officer (CIO) or chief technology officer. “As customers increasingly search for information and shop for everything, including financial products, online, it is the CIO’s role to ensure a digitally secure highway for information exchange,” says Munish Mittal, CIO of HDFC Bank. “Otherwise, an organisation’s ability to grow in this digital age is constrained and it risks losing out on business.”

But how does a company ensure that its digital vault of information is protected? The first step, says Mittal, is to build awareness within the organisation. HDFC Bank requires each of its employees to undergo a quiz-based certification on cybersecurity awareness periodically. There is a well-defined access management policy that spells out which employees should have access to what information, depending on the relevance and sensitivity of the data. In addition to installing advanced threat protection software, India’s second-largest private sector bank also conducts frequent penetration tests on its network to scout for vulnerabilities and remove them.

This is where entrepreneurs like 24-year-old Trishneet Arora come in. His firm TAC Security, which he founded in 2013, works with 50 clients across the public and private sector. “The cyberattacks are not surprising. This is just the beginning and there are more to come,” says Arora. “That is why enterprises need to simulate attacks on their own systems to identify loopholes and address them. If you want to catch a cybercriminal, you need to think like one.”

For instance, EY’s Fraud Investigation and Dispute Services team was brought in by a large digital media and content company (name withheld by EY) when it discovered that the password for its channel’s account on an online video aggregator content platform was reset without its knowledge and 25 of its most popular videos were deleted. The EY team stealthily used some forensic tools on the company’s network to review and analyse the network’s logs to check for any exceptional occurrences, as well as the email logs of authorised users.

The team could then reconstruct the series of events that led to the content being deleted. EY found that the change of password was effected through an internet browser on a mobile phone and that the content deletion command was triggered remotely via the back-up server of its client hosted by a web-hosting service provider. Tracking the ID used to access this web server, the team was able to pinpoint the location of the user. The address was a match with that of an ex-employee who quit the company a year ago on bitter terms.

Despite employing the best preventive measures, all IT systems in the world remain vulnerable to a hack. “It is a misconception for anyone to think that they can’t be hacked. Hackers are always one step ahead,” says Mittal.

Werner Vogels, chief technology officer at Amazon.com, tells Forbes India that a combination of machine learning and Artificial Intelligence-driven automatic pattern recognition will become increasingly important to detect and respond to potential threats. “Without security, you don’t have a business, but security these days is so complex that it is a moving target,” Vogel says. “There are instances of companies considering AWS [Amazon’s cloud service Amazon Web Services] purely because of the security capabilities we’re able to offer, with the kind of investments that they wouldn’t be able to make themselves.”

A paradigm shift is unfolding in the way that technology product makers and service providers encourage users to protect their data. Text and numeric passwords are progressively giving way to biometric-led security measures such as fingerprint and iris scanners. At a recent panel discussion on digital transformation organised by Forbes India, Samit Ghosh, managing director and CEO of Ujjivan Small Finance Bank, said one of the benefits of Aadhaar—the unique identification initiative for Indian citizens—was that it relied on biometric authentication, which is more secure than passwords.

A lackadaisical approach towards cyber hygiene—exhibited both by individuals and companies—including failure to change passwords frequently or updating a computer’s operating system with the latest software updates can add to a system’s vulnerability. For instance, the WannaCry attack impacted only those machines running on Microsoft’s Windows operating system that had not installed a security patch released by the company.

Its susceptibility to malware attacks and relatively lower cyber hygiene awareness make India a logical choice for companies providing security solutions. For instance, India is one of only eight countries in the world where Microsoft has a cybersecurity centre, which helps enable governments and private sector enterprises to build awareness and access to security experts to “anticipate, and not just react, to security issues”, says Anant Maheshwari, president, Microsoft Corp India. Separately, Microsoft also has a cybersecurity engagement centre in India that operates in affiliation with its Digital Crimes Unit (DCU), which helps identify and solve cybercrimes with the help of law enforcement agencies and bring cybercriminals to justice in a court of law. “Cybersecurity will always be a focus area for us. We invest more than a billion dollars each year globally to ensure security, privacy, and compliance in our products and services,” says Maheshwari.

The Indian arm of Microsoft’s DCU, led by Meenu Chandra, a senior attorney who specialises in intellectual property, participates in the company’s efforts to collaborate with peers worldwide to take down botnets (a family of malware worms that infect a network of computers). A so-called sinkhole (also known as a honeypot)—the parallel clone of an existing computer network to which the source of the malware is attracted—is used to trap the botnet and identify its location; law enforcement agencies then zero in on the criminal and capture him/her.

But the DCU’s role doesn’t end there. “Even after taking down the botnet, the systems on the other side of the network gateway don’t know that the source of the infection is gone. So the machines affected by malware still try and communicate with the source, which tells us how many systems are still out there that are impacted by malware. We compile this data for our cyber threat intelligence programme,” Chandra explains.

There is huge buzz around the new tech favourite, blockchain, a cloud-based distributed database used to maintain a continuously growing list of records (called blocks), with each block containing a time stamp and a link to the previous block. One of its key purposes is to enhance security and transparency in processes like financial transactions and supply chain management. IBM India, in fact, is working with the Mahindra Group to create a solution for the latter. “As a diverse federation of businesses ranging from agriculture to aerospace, Mahindra is uniquely positioned to leverage the benefits of a blockchain-enabled solution for supply chain finance in India. This initiative aligns perfectly with Mahindra’s tech and innovation-driven growth strategy,” Anish Shah, group president of strategy and a member of the group executive board at Mahindra & Mahindra, said in a blogpost on IBM’s website.

“Security has very high mindshare with customers, but very poor wallet share,” says Karan Bajwa, who recently took over as managing director of IBM India. While that is a challenge for the country, it is also an opportunity for players like IBM and Microsoft to build awareness and get customers to spend more on cybersecurity. Vital institutions like BSE have already bitten the bullet and entrusted third-party firms like IBM to develop an integrated security solution for them on a turnkey basis.

Companies like IBM and Microsoft have tried to shake the prevalent mindset among Indian businesses that a public cloud is unsafe by focusing on the fact that data is stored across multiple locations in a completely secure manner and that it is the full-time responsibility of the company that owns the cloud platform to ensure its dependability. They have seen some success with organisations, especially financial institutions like HDFC Bank and State Bank of India, migrating some portion of their operations to a public cloud.

Enterprises are doing their bit for cybersecurity, but policy measures also need to be revised to make these efforts more meaningful. For instance, there is no provision in general law for cybersecurity breaches to be publicly disclosed, unlike in the US. This explains why cases like those involving Zomato and Union Bank of India are rarely reported. Sharing intelligence around cyber threats helps companies prepare for such eventualities better but many prefer to not report such incidents for fear of embarrassment and backlash from shareholders. “We [the industry] don’t like to share our problems with each other too much but that will change with time,” Zomato’s Goyal tells Forbes India.

The financial services space in India appears to be better off with the Reserve Bank of India having issued a circular, in June 2016, on the cybersecurity framework at banks with some elaborate guidelines.

The circular asks banks to put in place a board-approved cybersecurity policy and crisis management plan; arrange for continuous surveillance and upgrade of network infrastructure and most importantly, report cybersecurity incidents with the regulator.

The Indian government also appears to be warming up to the idea of having more well-defined cybersecurity policies in the country. “A focus on cybersecurity is a critical component of the Digital India road map. The government’s focus is evident with the creation of a National Cyber Security Policy and a National Cyber Coordination Centre,” says Maheshwari. “I would also like to compliment the government in having set up a Cyber Swachhta Kendra in CERT-In (India Computer Emergency Response Team), which will focus on fighting malware in the country. I see a tremendous amount of eagerness in the government on adopting new-age technologies.”

Robert Mueller, the former director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation in the US, had famously said in 2012: “There are only two types of companies: Those that have been hacked and those that will be.” As ominous as those words sound, successive cyber incidents that come to light bear out their truth. Safeguarding one’s digital ecosystem is much like protecting one’s home. While it doesn’t guarantee averting a break-in, putting a lock on the door is always a good idea.

(With inputs from Harichandan Arakali, Anshul Dhamija and Paramita Chatterjee)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)