Factchecks and balances in the age of fake news

Professionals are taking on the rising surge of misinformation and rumours in India, but remain limited by resources and reach

Illustration:Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

Illustration:Chaitanya Dinesh SurpurIn August 2016, software engineer Pratik Sinha joined his mother Nirjhari on a 10-day protest march from Ahmedabad to Una, on the southern fringes of Gujarat, where seven Dalits were flogged by a vigilante mob for skinning a dead cow. During the 350-km march, Sinha documented the journey on Twitter with #ChaloUna. “For the first half of the march, there was hardly any media presence or coverage,” says Sinha. “But once the hashtag gained traction, the entire nation and the media woke up to the narrative of the Una march.”

The march also symbolised a paradigmatic shift in Sinha’s life: It showed him the social good that the internet could do. Born to Nirjhari and Mukul Sinha, an advocate who represented the victims of the 2002 Gujarat riots, and the Sohrabuddin and Ishrat Jahan encounter cases, among others, activism was something he had grown up with. But having trained and later worked in the US and Vietnam as an engineer, “my life was divorced from reality”, he says. “Till the Una march happened, and I realised this was what I wanted to do.”

Sinha quit his job and turned his focus on a scourge that he felt was on the rise: Misinformation. It was around the time when claims like the release of ₹2,000 notes with a GPS tracking nanochip, or of salt shortage that triggered panic-buying in multiple states were flying around. And Indians had taken to digital platforms, through which these rumours spread, like fish to water. A 2017 report by KPCB, a US-based venture capital (VC) firm, had stated that the volume of wireless broadband data consumed by Indians had increased from less than 200 million GB a month in June 2016 to 1.3 billion GB a month in March 2017. With the alternative information universe at an inflection point, Sinha, in February 2017, launched AltNews, a fact-checking portal to debunk fake news, images and videos.

Sinha, however, wasn’t the first to move into this space. In 2014, Govindraj Ethiraj, a veteran journalist and founder of IndiaSpend, the country’s first data journalism initiative, set up Factchecker ahead of the national elections. Inspired by the emergence of fact-checking practices in the US to verify statements made by presidential candidates, Factchecker, India’s first such project, started to check the veracity of comments made by public figures and institutions. Like Minister of Defence Nirmala Sitharaman’s claim that there were no terror attacks in India, except in Kashmir, since the BJP came to power at the Centre in 2014.

But Ethiraj soon figured there was a rising swirl of fake news that went under the radar, in the form of videos with juxtaposed images, software that could generate audio and video clips out of thin air, bots that could get a topic trending on social media, and all of which travelled like water from a fire hose on Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and Telegram. That’s when he spun off Boom, a full-fledged fact-checking initiative, in 2016 to combat a subterranean ecosystem that shows weeks-old pictures of resting soldiers as one taken hours before the Pulwama attack, or pictures from old political rallies to pass off as Narendra Modi’s roadshows for the 2019 elections.

RISE OF FAKES AND FACTS

The reach of social media among the Indian electorate was first capitalised upon by the BJP for the 2014 general elections, followed by the Aam Aadmi Party for the 2015 Delhi assembly elections. Ever since, other parties have caught up, leading to sensational claims being bandied around digitally by all sides of the political spectrum. But there has been an unprecedented spike of misinformation over the last year or so, much of it imbued with mal-intent. “If fake news around 2014 was at the Ranji Trophy level, now it’s the IPL or the World Cup,” says Ethiraj.

The problem is only expected to grow as more Indians get on the internet: The Cisco Visual Networking Index forecasts that India will see a four-fold growth in its internet traffic from 2016 to 2021, with the share of mobile traffic rising from 22.9 percent to 42 percent.

The trend is in keeping with the global explosion of fake news since late 2016, when the term gained ubiquity. It brought bread and butter for a community in Veles, a small-town in Macedonia, where over 100 pro-Donald Trump websites were housed, which fed fake news—like the Pope endorsing Trump—to global news streams. William Moy, director of Full Fact, a fact-checking organisation set up in the UK in 2010, says, “The internet makes anyone a publisher. Something that looks like it’s from an individual can be part of a planned campaign that can be paid for or manipulated. It’s hard to track who is responsible for what is circulated.”

What could somewhat correct the skewed balance between fake and real is the number of fact-checkers around the world, which has more than tripled since 2014, from 44 to 149 in 2018, according to a census by the Reporters’ Lab at Duke University, US. While there isn’t an India-specific count, the numbers are rising and emanate from a mosaic of institutional and citizen-led initiatives. Seven of these have tied up with Facebook and seven are among the 67 global signatories to the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) of the Poynter Institute.

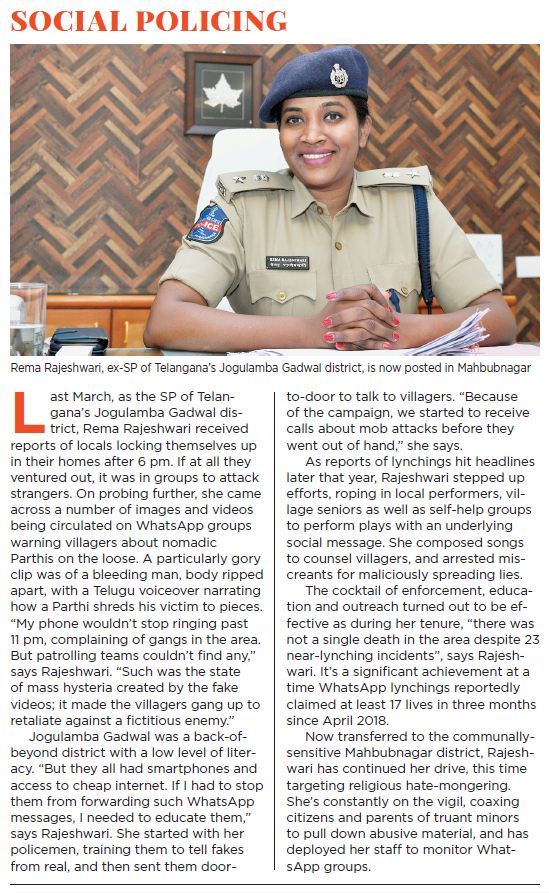

Initiatives such as AFP India, India Today Fact Check, Times Fact Check or Vishvas News have emerged from legacy media houses, while some like AltNews, Boom or Factly, founded by former engineer and data wonk Rakesh Dubbudu, work independently. Some others have stemmed from a personal crusade. Like SMHoaxSlayer set up by Pankaj Jain, a businessman by day and a fake news warrior after he puts his children to sleep; Jain took to busting myths when a deluge of WhatsApp forwards got on his nerves.

The organisations corral misinformation by monitoring daily news and social media content, crowdsourcing it through their portals or WhatsApp groups. Once the most vicious news items are identified, they are filtered through online tools like Google reverse image search, CrowdTangle, InVid etc, or the classical techniques of journalism—reaching out to local authorities and people on the ground.

“In India, news and rumour on social media get amplified through TV, which has a viewership of close to 900 million. The social media universe is just about one-third of that; and of that, the fact-checking initiatives are able to address a very small part, so it won’t have the multiplier, let alone corrective, effect some hope it to have. But their significance lies in being an indicator of trends in types of false news, their spread and circumstances generating it,” says Vibodh Parthasarathi, on leave from Jamia Millia Islamia, Delhi, and fellow at Metaforum KU Leuven, Belgium.

POLITICS OF FAKE NEWS

Fake news isn’t only triggered by elections, but comes in thematic waves. Says Ethiraj, “Last year, I had thought that misinformation would slow down once the Karnataka elections got over. But then the Kerala floods happened, and the volume of fake news was mind-boggling.” Sinha of AltNews recalls that social media was inundated with videos of Muslims celebrating a Pakistani win over India in the aftermath of the Champions Trophy final in 2017. “We debunked all the videos except one. It was one of our first stories to go viral,” he says.

But politics, and elections, are a good trigger. A study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), which parsed 1.26 lakh Twitter cascades (shares and re-shares of tweets on a particular subject), shows politics comprised the biggest news category, followed by urban legends, business, terrorism and science. Moreover, false political news reached more than 20,000 people nearly three times faster than all other types of false news reached 10,000 people. In the Indian context, the Pulwama attack and the consequent Indian airstrikes in February—news that lies at the intersection of politics and terrorism—brought in a flood of misinformation. Boom busted around 30 fake items in the week following the attack, and nine on the day after the attack, triple its usual dose.

The political preference of fake news is a global phenomenon, with organisations like US-based Snopes, the grandfather of fakebusters set up in 1994, noticing a perceptible shift, from mostly hoaxes and folklore to political misinformation, around 2008. “It was since the US presidential elections when a lot of conspiracy theories, like Barack Obama being Muslim or that he had a fake birth certificate, were being floated,” says David Mikkelson, founder of Snopes.

“Most people don’t pay much attention to elections until it’s time to vote. The online traffic for elections peaks right before. It’s not surprising that in these times there is a much bigger audience for inaccurate information,” says Moy of Full Fact.

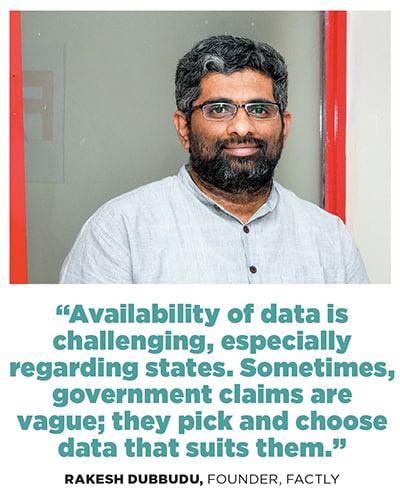

What makes these times particularly challenging for fact-checkers in India is the lack of credible information. Of late, India’s official statistical claims are being taken with a pinch of salt, as the government keeps revising datasets, raising allegations of covering up numbers that it construes as inconvenient. Such data ambiguity means fact-checkers need to generate their own numbers through Right to Information applications and multiple other sources. “Availability of data is challenging, especially when it comes to the states. Sometimes, government claims are vague; they pick and choose data that suits them. For example, for GDP comparisons, the Congress still talks about 2007-08, because it was their best year, while the BJP talks about another timeframe,” says Dubbudu of Factly.

For citizens to get around this problem, Factly has launched an open data platform, Counting India, which affords easy-to-use Census data through maps and interactive visualisations; it plans to expand the services, like bringing in comparisons between the demographics of two districts. While the platform is aimed at journalists, it would be open to the public as well. Factly also plans to launch a dedicated portal for journalists later this year and are exploring a revenue model to monetise this tool. Similarly, it is building an open-source publishing platform, degafactcheck.com, for best practices within the fact-checking community, stipulating standardised guidelines for those wanting to fact-check a story.

UPHILL TASK

But while taking on fake news is one task, reaching as many consumers with the rebuttal is another. Falsities trump truth in dissemination, as established by the MIT study: Whereas the truth rarely reached more than 1,000 people, it says, the top 1 percent of false news reached between 1,000 and 10,000 people. Falsehoods were 70 percent more likely to be retweeted than the truth, perhaps because they substitute the boring and obvious with the exciting and unusual.

For instance, a Facebook Live post by one Avi Dandiya on March 1 claiming that the Pulwama attack was orchestrated by the BJP clocked 1 million views in less than 24 hours before AltNews picked it up for fact-checking. By the time they published the rebuttal, the fake video was seen by 1.8 million people. Dandiya eventually took it down, but not before it had over 2 million views and 1 lakh shares. In contrast, the AltNews story that proved that Dandiya had doctored the video by stitching together separate interviews had a little over 20,000 shares. “Publishing nonsense takes minutes, while checking it and issuing a rebuttal take hours. There is always an issue about the response being slower and less well-distributed,” says Jamie Angus, director of BBC World Service, who recently commissioned a study about the fake news problem in India.

Like the hours it took AltNews to slice and dice the viral video of a youth (allegedly Muslim) molesting a minor, shot on a phone, without a time or location imprint. They examined multiple frames to identify the number plate of a passing car, contacted police stations in Shamli, the UP district in which the car was registered, and zeroed in on the complaint to find the youth had a Hindu name.

The effort could roll into four or five days as Sinha describes their probe into claims that Shehla Rashid, a student political leader from JNU, had consumed funds collected for families of Unnao and Kathua victims: Very few people were willing to come on record, it was difficult to get hold of copies of passbooks to record funds transfer and even tougher to reach people in Kathua, located in far-off Kashmir. “You can never catch up with virality. The action has to be post-facto,” he says.

During the Swedish elections in 2018, an international initiative set up a pop-up newsroom to identify and debunk false news in real time with the use of digital tools like Check, Krazana and TweetDeck. But the template might not work in India, given the number of users and multiplicity of languages, compared to the small, largely centralised and effectively monolingual Swedish social media landscape, says Parthasarathi.

In India, AltNews is experimenting with tamping down on the velocity of fakes with an app that is now in beta testing. Once it’s rolled out, anyone can feed an image or video into the app, which will throw up in some seconds the original image or video if it has already been checked. “The main challenge of raising criticality is that people who are doing fact checks and those consuming misinformation are two different subsets. With this app, we are hoping to create points of intersection between the two,” says Sinha.

The media house is also planning to come up with a school curriculum to introduce children to the perils of fake news. “We are hoping some sympathetic state governments will pick us up,” says Sinha. Last year, Boom ran a workshop for Google, training about 8,000 journalists to spot fake news.

THE ROAD AHEAD

What makes the global fact-checking landscape restrictive is that most independent fact-checking organisations are registered as not-for-profits and operate in a startup mode. While VC firms don’t invest because of limited growth opportunities, fact-checkers too are wary of such funding as it might mean ceding control. “The moment the VCs get involved, scale and volume come into the picture, which will lead to us getting into the breaking news cycle. In the foreseeable future, apart from the business ideas we are pursuing, there will be a lot of grants allotted in this space,” says Factly’s Dubbudu.

“The challenges that fact-checking organisations face are lack of resources—financial and human capital—and the absence of a competitive media atmosphere. They are like startups when compared to traditional media outlets, and a lack of monetisable exit plans make it a space for only highly-motivated journalists driven by advocacy,” says Baybars Orsek, director of Poynter’s IFCN. In 2018, the network awarded a grant to Factly to write 100 fact-checked stories about the performance of the Modi government from September 2018, leading up to the elections.

In India, the community survives mostly on grants, subscriptions, donations and tie-ups for content sharing, working out of modest offices with a handful of employees. “This work is not something that investors will buy. Doing good and making money are not related in most cases,” says Ethiraj. UK’s Full Fact wants to cap funding from a single source at 15 percent to avert overdependence on a donor, but still can’t; last year, Google breached the mark.

This is also an area where few will look towards advertising money. For one, it might mean compromising their integrity, and second, these sites shy away from a regular news cycle, mostly dishing out content reactive to the goings-on.

It brings the Indian audience, with a propensity to consume digital stuff for free, to a crucial juncture, where they have to step up and pay for what they read. Sunil Rajshekhar, CEO of Independent and Public-Spirited Media Foundation, which provides grants to media platforms like The Wire and AltNews, says, “People have begun to pay for credible news online. We believe that readers today are conscious about such media needing their support. More and more readers are getting involved with content from independent media and are willing to pay to continue to read content they can trust.” Besides, open-source data, as is promoted by the likes of AltNews and Factly, is expected to have an indirect reach that is many times their direct reach, and will bring in more subscribers, the founders hope.

That apart, digital platforms like Facebook and Google are the chief sources of revenue for most, funding studies, commissioning training programmes and roping them in on their respective platforms. But such tie-ups can be a double-edged sword as organisations like Snopes and Associated Press have pulled out, citing limited intent. Mikkelson wouldn’t divulge much, just that “if we are taking the risk of doing what we are, we should be allowed to do a lot more”. In a news report by The Guardian in December 2018, journalists associated with Facebook’s fact-checking project said they have lost trust in the platform.

“It’s a question of the market power in the online world, which, at the moment, is in a few hands. Unless it gets diversified, players who depend on these behemoths for ads or recently for collaborative solutions will not find themselves truly independent and, over time, risk losing credibility. Can we imagine a different ecosystem where the social media landscape is less concentrated?” asks Parthasarathi.

What does such a crisis of confidence mean for Indian fact-checkers? Says Ethiraj of Boom, which earns much of its revenue from Facebook since its tie-up ahead of the Karnataka elections last year, “If we are trying to fix the problem of misinformation, I think anything we are doing by suppression or distribution through social media is a step forward. The problem is large and all the effort that we put in is important.”

The biggest perhaps is to keep the chin up as the volume of misinformation swells. As Mikkelson of Snopes says, “From fact-checking and journalism, the pendulum has swung very far in one direction towards fake news. We’ve got to push it back towards the other.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)