HDFC Mutual Fund Unwavered by Recent Failures

HDFC Mutual Fund’s Prashant Jain is unapologetic about the recent poor performance of HDFC Top 200, the country’s biggest fund, despite some mistakes in picking the wrong stocks and sectors

HDFC Top 200 is the biggest fund in the country with a size of around Rs 9,765 crore as of August 2013. It has been one of the best-performing funds over the long term, managing to beat the index by a wide margin. But it has been a laggard over the last one year, when it moved away from the banking sector, which accounted for 25 percent of holdings (where SBI was the top holding at 7.75 percent). This year, Jain’s big bet is software, at 16.5 percent, with Infosys accounting for the bulk at 9.35 percent. Banking accounts for 19 percent, showing that the fund has changed its preference to go with the present tide.

Fund analysts feel size is the enemy of HDFC Top 200 as it brings in liquidity issues for the fund. But when Forbes India talked to Prashant Jain, executive director and chief investment officer at HDFC Mutual Fund, he disagreed. Jain does not deny that the fund made some wrong calls on stocks, but those are the only reasons for underperformance. Size doesn’t really matter and investors should not fret about the fund. Excerpts from the interview:

Q. HDFC Top 200 is trailing the benchmark this calendar year year-to-date after many years of beating the benchmarks. What has changed?

It is correct, that in the current year the fund is lagging the benchmark by nearly 4 percent. It is also correct that the fund has bettered the benchmark by a reasonable margin in the past; over the last 5, 10 and 15 years the fund has bettered the benchmark by 4.3 percent, 6.5 percent and 5.9 percent per annum [taking the net asset value as on September 6, 2013]. What has not worked for the fund this year is an optimistic view of the economy and the fund’s exposure to banks.

The sharp depreciation of the rupee has created additional pressures for the economy and we have taken some corrective steps to realign the portfolio to the changed environment.

Q. You have often said difficult times give you a chance to learn. Your funds have been through a rough patch in 1995, then in 1999, then in 2007, and now in 2013. What have you learned this time?

It is true that tough times teach more than good times. I am fortunate to have experienced several tough periods, made mistakes, learned each time and survived. I think, I have not made the same mistake twice and hopefully will not do so in future.

The learning this time has been that it is hard to forecast the economy, particularly over short periods, and that the external variables are increasing for India. A second observation is that increasingly decisions are nowadays being driven by narrow considerations and not by what is in the long-term interests of the country.

Finally, the turn of events has re-emphasised the age-old advice that one should live within one’s means. This applies in equal measure to individuals, countries and governments; and that if one has to borrow, it is better to borrow at home than outside.

Q. Is the size of the fund not an issue for performance?

In my opinion, this thought is an illusion that keeps on coming back for as long as I can remember. In a universe of, say, 100 funds, there will be large funds and there will be small funds. When a large fund underperforms, it is noticed a lot more and the easiest conclusion is that size is to blame; when a small fund underperforms, it is simply noticed less and size cannot be blamed.

Reality, in my opinion, is that there is no correlation between size and performance; anyone who feels this way should arrange all funds either in order of size or performance and the picture will be clear. Actually there are no large funds in India; the largest fund is less than 0.2 percent of the market capitalisation!

Q. What will be the effect of a weaker rupee on Indian companies?

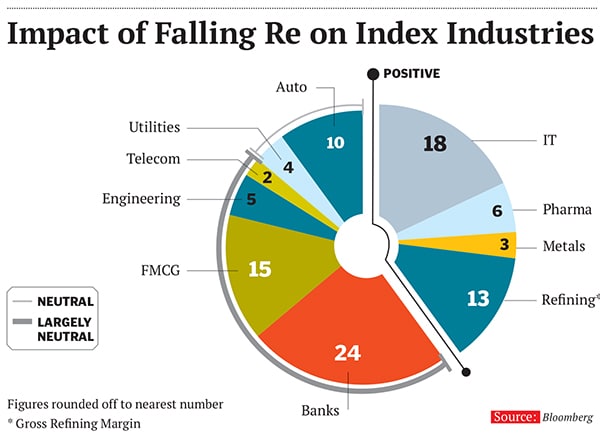

This is an interesting question. The composition of the S&P BSE Sensex as on September 10, 2013 is as follows. For IT, pharma, metals and refining, with an index weight collectively of 40 percent, the impact of rupee depreciation is positive. For the rest, with a weight of 60 percent in the index (banks, FMCG, engineering, telecom, utilities and autos), the impact is largely neutral or negative.

A falling rupee is positive for the first category, largely neutral for the second. It is negative for a few companies. Thus generally, rupee depreciation is positive for the profitability of S&P BSE Sensex companies. It is, however, negative for companies that have large amounts of foreign currency debt that has been used to fund local assets. It is also generally negative for the economy as it increases inflationary pressures and puts additional pressure on the fiscal deficit by increasing the import parity prices of oil products, fertilisers, etc. A weak economy, in turn, is indirectly negative for banks.

Q. You have generally avoided being in cash. Does it not make sense to increase cash holdings in difficult times?

There are a number of reasons for this approach. First, in my opinion, timing the markets in the short run is extremely difficult. Even professionals have a bad track record at this; cash holdings in mutual funds in general were very low at close to market peaks in 1999 and in 2007; on the other hand, cash holdings were high at close to market bottoms, the most recent case being in 2008.

Second, I feel that investors are doing asset allocation at their end. They are investing only their risk capital in equity funds and they take a long-term view of equity investments. The total size of equity mutual funds, at nearly $27 billion (Rs 1.78 lakh crore on September 6, 2013) is just 2.7 percent of household financial assets. This highlights the minuscule exposure to equities and reduces the need for equity funds to time the market.

The above does not deter us from sharing our medium to long-term views on the market with investors to help them optimise their asset allocation; for example, in January 2008, at close to market peaks, in a note titled ‘Fun with Averages’ we had highlighted [the point] that the returns over medium periods in the indices should be moderate. This was largely driven by the prevailing high price-earnings (P/E) multiples then and it has turned out to be largely correct.

It is an altogether different matter that consistently the bulk of the monies in equity mutual funds come at high P/E multiples and that at low multiples there are little or no inflows.

Q. You have followed a concentrated approach to investing. Some call it excessive risk taking. I have followed my convictions in life and in investing; after all what good are convictions if one does not act on them?

This approach has caused pain on some occasions in the short run, but the rewards have been generally good over the long run. Selling IT stocks in 1999 [after which they doubled before collapsing 70-90 percent], not owning real estate, power utilities and NBFCs in 2007 all caused pain in the short run but not in the long run. At the same time, high exposure to corporate banks in 2012-13 has been a mistake and we took corrective action. Thus, while acting with confidence, one is not dogmatic and inflexible when a mistake is realised.

Finally, in my opinion, “focussed” is a more apt description for this approach to investing. There are a few simple but effective measures in our investment process that prevent high concentration, particularly with respect to the benchmarks.

Q. You have completed 20 years of managing the Top 200 Fund. What has changed for the portfolio over the last two decades?

This is only partly correct; I have been managing the Top 200 Fund for not 20 but 13 or 14 years. I will, however, be completing 20 years in February 2014 of managing the Prudence Fund, a fund that I have managed since inception.

Like most things in life, a lot has changed in this time. Information availability and sell-side research has increased manifold, mutual funds have gained in acceptance, a career in investing is more respectable now, etc. On the other hand, some things have not changed—fear and greed are as much a part of human nature today as they were then. This is why even today the bulk of the money in stock markets comes at close to market tops, as it used to then.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)