Infosys: Whistleblowing or crying wolf?

Infosys has been no stranger to anonymous complaints, but the whistleblower mechanism may have just devolved into a tool to rock the IT services giant's boat

Infosys CEO Parekh has led a strong recovery, but the whistleblower complaints since September 20 have cast aspersions on that

Infosys CEO Parekh has led a strong recovery, but the whistleblower complaints since September 20 have cast aspersions on thatAbhijit Bhatlekar / Mint Via Getty Images

Be careful with this message, warned Google Mail on October 20. It was referring to an 8.42 am email in my inbox. “‘Whistleblower’ has never sent you messages using this email address,” opined Google, with an auto option to report the sender for phishing.

Indeed, the Sunday morning email was from an Infosys whistleblower, but from a new username and domain address. It wasn’t from the Infosys whistleblower of 2017 and 2018, which came from a different email address and username.

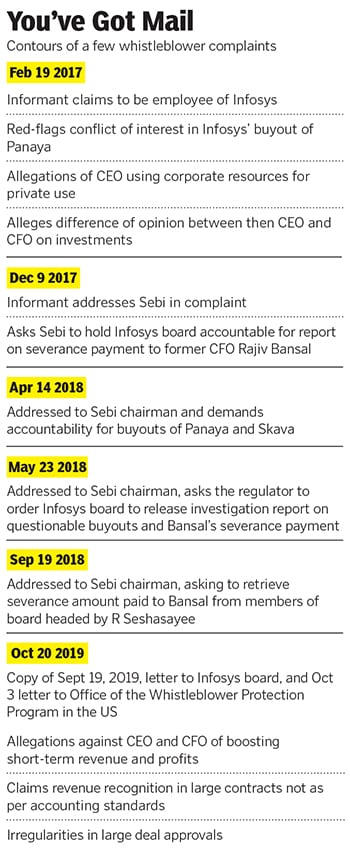

The 2017-18 batch of whistleblower complaints had built on a set of explosive moot points from yet another whistleblower in 2016, which centred around “serious corporate governance issues and conflict of interest issues” under Vishal Sikka, the CEO of Infosys until August 2017.

Marking journalists on emailed whistleblower complaints had become a covert method in the 2017 campaign to usurp Sikka, and change the board of directors under R Seshasayee, giving the informants mileage on mass media. WhatsApp, an instant messenger, enhanced the whistleblowers’ reach. The campaign ended with the resignations of Sikka and Seshasayee.

The allegations were never proven, at least not to the public. This was unusual for Infosys, in which promoters control only 13 percent of a publicly-listed company, and hence leaned towards a culture of timely disclosures and accountability. But the Infosys board under chairman Nandan Nilekani neither admitted nor denied the findings of the 2017 inquiry into the Panaya buyout. The whistleblowers had repeatedly questioned the acquisition. The board, satisfied with the independent inquiry, wanted Infosys back to business.

Apart from journalists being privy to the complaints, there is another common feature between the October 2019 and the 2017-18 complaints. (Forbes India has copies of these.) In all instances, emails were marked to six or more officials of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi), including its chairman. This legitimised the complaint, making it believable.

But does that mean whistleblower allegations are based on evidence, or can be cross-verified? Are the recent whistleblower charges—against Infosys current CEO Salil Parekh and CFO Nilanjan Roy—in the October 20 email true? Or has the whistleblower mechanism devolved into a tool to rock the Infosys boat again in the WhatsApp age? In a November meeting with investor analysts, Nilekani addressed both sides of the predicament.

First, the scope for misuse. He said: “If a company does not have the opportunity to thoroughly investigate any complaint, this (whistleblower) right could inappropriately shift from a corporate safeguard to becoming a conduit for abuse, allowing an individual to manipulate a company’s operations or reputation without due process.”

While replying to an analyst’s question later, Nilekani stood up for whistleblower protection: “Please understand… If a whistleblower has raised a genuine issue and is dealing with the company, he should be protected against the company…We are not in the business of finding out who did it. That would be inappropriate.”

How It Happened

In the October 20 email to the media, the whistleblowers (identified as ‘Ethical Employees’) questioned the Infosys management’s accounting practices. In the past four quarters, the company has reported year-on-year growth rates ranging between 8.4 and 10.6 percent.

The allegations against Parekh and Roy were first spelt out in a complaint dated September 20, a month before it was forwarded in an email to the media. Infosys claims it became aware of the allegations on September 30, after a board member got the complaint titled ‘Disturbing Unethical Practices’ and another (without a date) ‘Whistleblower Complaint’.

According to a source, the complaints did not have any evidence. Neither did Infosys get email evidence or voice-recordings in support of the allegations, which the informant claims to have enclosed in a letter to the Whistleblower Protection Program (WPP) under the US Department of Labor in Washington DC. This letter to the US was dated October 3, and substantiated the claims made in the first complaint by ‘Ethical Employees’.

This letter was also the most sensational, as it suggests that details of supporting evidence were enclosed. Its subject refers to “wilful mis-statement and material accounting irregularities…” Infosys learnt about this complaint on October 16.

According to securities law, the onus lay on Infosys to respond to an informant even without evidence. Any whistleblower policy kicks into action from the time a company receives the complaint. According to the Infosys Whistleblower Policy, “All reports under this Policy will be promptly and appropriately investigated, and all information disclosed during the course of the investigation will remain confidential...”

Infosys says it placed the whistleblower complaints before its audit committee, chaired by financial expert D Sundaram, on October 10. It was then placed before the non-executive board members on October 11, the day the company announced its second-quarter financial results and its management faced investor analysts and the media. But they didn’t mention anything about the complaints.

On October 20, when members of the media received this complaint by email and reported it, the issue started to reverberate across stock markets. The ‘Ethical Employees’ had scored; the Infosys’ board had been late.

“On October 18, two days before the complaints were made public, the chair of our Audit Committee decided to retain outside counsel to conduct an independent investigation of the matter,” Nilekani told analysts on November 6. It appointed law firm Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co on October 21, the day the whistleblower complaint was put out by the media.

Infosys informed the stock markets on the same day, but the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) and National Stock Exchange of India were closed for Maharashtra elections. So the Infosys American Depository Receipts (ADRs) took the first hit—a 15 percent fall—on the New York Stock Exchange. The Indian stock markets followed, as the stock dropped by 16 percent.

On October 23, Sebi and the BSE sought a clarification from the company for non-disclosure of information about the complaint. “In this case, there are very specific allegations—like cited contract, clients—without evidence,” says Shriram Subramanian, founder of InGovern, a firm that advises financial investors on proxy research services. “It isn’t easy to discern the seriousness of the complaint. That is just the nature of the beast: The whistleblower mechanism. And the company erred on the side of not disclosing.”

“It could even be factions within a company. So it is tricky, with no easy way to discern the seriousness of an anonymous complaint,” says Subramanian.

TV Mohandas Pai, former finance and HR head at Infosys, told Forbes India: “Whistleblowers can write to anybody today. Every company must have an independent process to evaluate and take action. But if people go to the media after filing the whistleblower-complaint with the company, what can anybody do to prevent it? Nothing can be done.”

The whistleblower mechanism took root at Infosys in April 2003. Pai recalls the company was in line with the global response among corporations to protect shareholders from another Enron in the US. “Before the whistleblower policy was formed, employees sent emails to the chairman or HR, or whoever they wanted within the company. Today, people can send emails to anybody they want,” he says.

If so, how do Sebi officials or board directors know that a whistleblower letter is legitimate, as opposed to a tactic to derail a company’s management? Not to forget, the danger of insider trading.

The October 20 email, whose contents got published, had specific details of deals and names of clients that made the allegations against the management seem credible, adds Subramanian. Once published, whistleblower complaints can fuel speculation far more potently than market rumours, and long before any allegations get proved.

“It can also be carried out by outsiders who have taken sharp positions in the market,” Subramanian says. According to business news daily Mint, Sebi was investigating a buildup of derivatives positions in Infosys stock before allegations of accounting malpractices surfaced with the whistleblower complaint that became public knowledge.

“Under listing guidelines, all material information needs to be disclosed to the stock markets,” says Ramesh Vaidyanathan, managing partner of Advaya Legal, a law firm. “But whistleblower allegations are not material until proven to be true. If companies find something to be materially wrong based on whistleblower information, the nature of the complaint has to be disclosed without going into the content of whistleblower letters,” he explains.

So how does the regulator cope with these complexities? A Sebi consultation paper dated June 10, 2019 has recommended an Office of Informant Protection (OIP) for whistleblowers to directly make a complaint to Sebi. The regulator thinks this mechanism can reduce, if not prevent, insider trading. The OIP is envisaged as a way to process the veracity and authenticity of information received, analyse the application of regulations and even decide upon the issue of granting a reward to the informant after Sebi takes enforcement action. “The proposal is still in the pipeline,” Vaidyanathan says.

Another recommendation is that a legal representative will verify the identity and contact details of the informant, and ensure that the identity as well as the informant’s disclosures are kept confidential. This mechanism is crucial to ensure fair redressal of complaints, depending on evidence shared by whistleblowers rather than anonymous informants.

Infy under Parekh

Analysts were peeved at Infosys’ delay in disclosing news of the whistleblower complaint it received on September 30. “The board signed the audited numbers despite this (whistleblower) letter, suggesting that they did not believe there was anything that vitiated the financial statements,” stated a research analyst report by Investec Bank.

After Nilekani explained the updates to analysts on November 6, many brokerages and investment firms recommended ‘HOLD’ for the Infosys stock. But on November 12, news agency IANS reported another whistleblower letter. This one made accusations against Parekh for not settling down in Bengaluru, but living in Mumbai among other things.

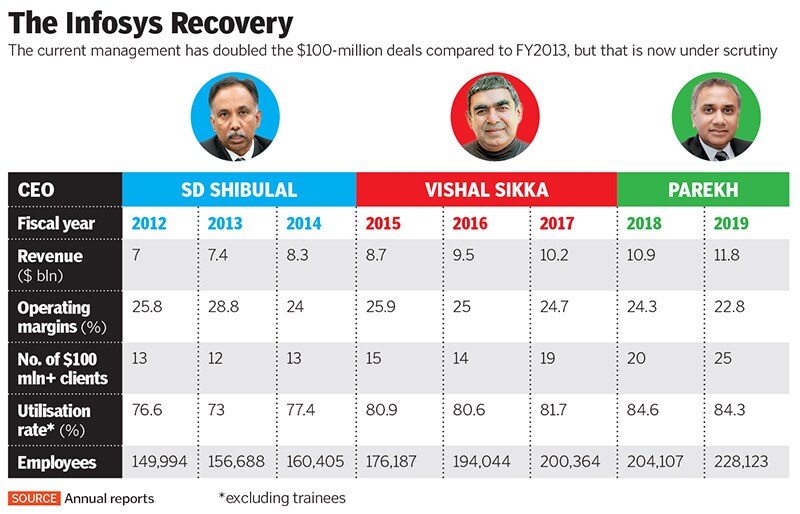

But the most materially-significant test facing Infosys is to prove that its books of account are clean. Its regulatory filings show that Parekh has led a strong recovery from the tumultuous tenure of Vishal Sikka, which ended in August 2017. The whistleblower complaints since September 20 have cast aspersions on that.

According to Infosys’ 2018-19 annual report, the number of its clients who contribute more than $100 million each year improved from 14 to 25 in three years. The whistleblower complaint claims “revenue recognition matters are forced which are not as per accounting standards”.

Winning and renewing large outsourcing deals is important for IT firms to utilise their substantial talent pool. Infosys had 2.28 lakh employees, as of March 31, 2019. And its utilisation rate (excluding trainees) is up from 80.6 to 84.3 percent in the same period. Parekh has steered this with the focus on large deals to utilise the talent base.

While Infosys clocked 9 percent growth in constant currency terms to come within touching distance of $12 billion in 2018-19 revenue, followers—particularly old-timers—rue the drop in operating margin. It has moderated from 25.9 in FY15 to 22.8 percent in FY19.

But this is an outcome of how competitive the market for IT outsourcing deals has become. In 2009, large vendors TCS and Infosys were seeing clients come under pressure after the Lehman Brothers crisis. But the competition from its smaller peers was less.

More mid-sized IT offshore service providers from India—TechMahindra, L&T Infotech, Hexaware, Zensar—have upped their deal-sourcing capability from a decade ago. On the supply side, “smaller competing players begin with a lower starting price”, noted ISG (Information Services Group), a technology advisory firm in its October 2019 ISG Index. On the demand side (clients), ISG notes “enterprises are watchful of external factors, which impacts propensity to spend”. Clients have been in caution mode.

Large IT outsourcing (ITO) deals are still the bread-and-butter business of Indian IT firms. And the US is still the largest contributing market for large IT firms’ revenue. But the value of ITO deals in the Americas has crawled from $7.2 billion in the first nine months of 2017 to $7.5 billion in the same period of 2019, according to the latest ISG Index.

Europe, Middle East and Africa were worse. Value of ITO deals shrunk from $7.1 billion in the first nine months of 2018 to $6.6 billion for the same period this year. In this backdrop, Infosys renewed or won deals like ABN Amro and Volvo in Europe, and Verizon in the US. But with more choice, clients call the shots while renewing such deals.

“Where average total contract value was $78 million, 66 percent of managed services deals see competitive renegotiations. (And) incumbents lose 70 percent of such deals that come up for renegotiation,” states the ISG Index.

The September 20 whistleblower complaint claimed that “several billion dollar deals of last few quarters have nil margin… In large deals finance team, important employees are *sic* left due to pressure to make deals look good.”

This brings to fore a home truth of why and how ITO deals are financially engineered. “The fact that there is financial engineering in deals, presumably with zero margins, should not surprise anyone,” says Sid Pai, former president of ISG Asia-Pacific, who had been lead negotiator for over $20 billion in deals, including the first large deal ABN Amro inked with TCS and Infosys in 2005. “If there are allegations of revenues or profits not being accounted for correctly, or of withholding information from auditors, they are serious and need to be probed by the board,” says Pai. “However, doing large deals with varying margins and using financial engineering to deliver greater value to clients upfront is normal practice for all firms in this industry.”

Financial Engineering

Deals are structured in a way that the IT service provider gives more value to enterprise clients in the first few years of the contract. So, in many instances, the first couple of years prove to be unprofitable for service providers. “The deals are engineered in a way that the profits from the deal accrue to the service provider (IT vendor) in later years of the contract. This is a common feature of the IT outsourcing industry, especially when the environment is very competitive,” Pai explains. It hasn’t been common in Infosys, though.

One of the main reasons Infosys has struggled to win large deals is it never compromised on margins, says a former senior manager at Infosys. “There was always a conflict between the sales guys and finance. All the hard work was done by sales, involving up to hundreds of people across geographies for more than six months to win a large deal,” he explains.

”The idea would be to win a large deal, even with thin margins, in a cost-neutral way, and then work the margins up. But, first, the sales team had to win the deal. Unfortunately, large deals wouldn’t come to us at 20 percent margins in competitive conditions. The finance and legal teams became gatekeepers,” he recalls.

This worked robustly for Infosys when deals were aplenty and large Indian IT firms were in demand. The global biggies like IBM and Accenture were still growing their offshore centres to retain customers. Fewer foreign enterprises had offshore facilities in India. So, TCS and Infosys didn’t have competition at scale until Cognizant upped the ante, overtaking Infosys with speed in closing large deals.

As the market became more competitive after 2011, sales teams within Infosys found the internal demand on margins stifling. Large deals took months to close. It also helped TCS and Cognizant get perceived as being flexible and more customer-friendly.

Chasing the New

Every Infosys CEO has faced stiff resistance from that Old Guard legacy since 2011, according to three former Infoscions. Under SD Shibulal, Infosys talked about a ‘new normal’—a cue for the need to accept what is good for clients (price) who were facing budgetary pressures. In 2015, Sikka advocated a product and platforms foundation to take Infosys on a high risk, high value path. That meant high margin, but after a wait.

Parekh, when appointed, was seen as the right person to navigate Infosys as a people’s company (as opposed to Sikka’s top-down product philosophy). But Parekh still needed to listen to his customers’ demands.

One school of thought among the three former Infosys senior managers is that Parekh may be facing the heat for taking responsibility in closing large deals based on client comfort. With this path, he is prioritising Infosys’ customers above Infosys’ margins in the near term.

The board has his back, as Nilekani reaffirmed to analysts: “The management is fully within its rights to select large deals and see it in the overall context of what needs to be achieved… We must let the management perform their job, and this is not a matter of whistleblowing. Large deals is entirely the prerogative of the company to decide what margin they should take it at.”

Second, senior leadership will get rationalised—roles will be done away with—or transformed (re-skilling) as enterprises get digitised. This is a reality that is playing out at $16 billion Cognizant Technology Solutions under new CEO, Brian Humphries.

In late October, Cognizant announced that as many as 12,000 mid- to senior-level employees’ roles are becoming redundant. This means the company will let go of 7,000 people, and re-skill the remaining 5,000 for new roles that are getting created. In addition, Humphries is adding 500 sales-focussed managers with varied backgrounds like business finance and commercial law. He wants Cognizant’s sales force to win a greater share of new digital business, without taking their eye off large deals. For this, Cognizant will move to a more leveraged sales compensation plan from January 2020, with at least 70 percent of the base fixed and 30 percent variable.

“There will be strict parameters in terms of what they are required to sell, which will enable us to ensure that people do not follow the path of least resistance (which is what they sold yesterday), but readily embrace the things that we need them to sell as part of our digital strategy,” Humphries told an investor analyst at the third-quarter 2019 earnings call in October.

Cognizant is not nudging—it is bulldozing their sales, business finance and legal teams into expanding the New (digital business). That’s what CEOs of IT companies are paid to do: Take decisions with limited information available, in ambiguous conditions, win large deals for the offshore delivery teams to innovate for clients at scale.

The board under Nilekani, a non-executive chairman and co-founder, is fostering a culture in operations that departs from micro-managing decisions. This innately means more trust to take faster decisions for clients.

“This game is not a rising tide that lifts all boats,” Nilekani told analysts. “It will go to those companies that get their strategy correct, that will get their execution correct, that will rebuild the skills of people that build new services and transform the way they do things.”

In this context, the points flagged off by whistleblower ‘Ethical Employees’ will prove to be one of two things: Materially significant to punish Parekh. Or, self-preservation to delay the inevitable.

But if Parekh is innocent, Infosys’ shareholders will always have two worries looming: What happens when the next whistleblower cries ‘wolf’ in the media? And will anybody believe a whistleblower if he or she actually tells the truth?